Anxiety

A New Way of Treating Depression, Anxiety, and Trauma

A new functional model of emotional disorders.

Posted November 26, 2021 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Neuroticism is a trait characterized by a tendency to experience frequent and intense negative affect, such as anxiety, sadness, or rage.

- Neuroticism may reflect a shared vulnerability for various emotional disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and trauma-related disorders.

- A new treatment for emotional disorders is called the “unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders,” or UP.

Are psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression truly different from each other? Or might they be part of the same syndrome?

A recent paper by David Barlow and colleagues from Boston University, published in the October 2021 issue of Current Directions in Psychological Science, suggests some psychological disorders (or “emotional disorders,” as they call them)—such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and dissociative disorders—are variations of the same syndrome. And central to this syndrome is neuroticism.

The Personality Trait of Neuroticism

Many years ago, psychologist Hans Eysenck suggested that mental illnesses result from interactions between stressful events and the personality trait neuroticism.

What is neuroticism?

In an interview, David Barlow defined neuroticism as “the tendency to experience frequent and intense negative emotions in response to various sources of stress along with a general sense of inadequacy and perceptions of lack of control over intense negative emotions and stressful events.”

Naturally, when someone believes challenging and potentially stressful events are unpredictable and uncontrollable, they are more likely to avoid the events or respond negatively both to the events and to the negative emotional experiences.

One way neurotic people try to reduce or prevent negative emotions is through avoidant coping (also called avoidance coping). Some examples of avoidant coping are distraction, reassurance-seeking, avoidance of anxiety-provoking activities or situations, and engaging in safety behaviors. Even worrying may be associated with avoidant coping, since a function of worry is to protect the individual from directly experiencing unpleasant emotions.

Because avoidant coping temporarily reduces discomfort, it may seem like a good long-term strategy for reducing negative emotions. But it is not. In the long run, people who use avoidant coping often experience more frequent or intense aversive emotions.

In addition, engaging in behavioral avoidance means there are fewer opportunities to challenge one’s erroneous beliefs. So, corrective learning never occurs. For example, a person with a phobia of dogs who avoids dogs all the time never learns that most dogs are harmless.

A New Model of Emotional Disorders

What maintains both neuroticism and emotional disorders, then, is “emotion-motivated avoidant coping.” As the authors note, “it is this aversive reactivity to emotional experiences and resultant emotion-motivated avoidant coping that form the bridge from neuroticism to the emotional disorders and that are... the transdiagnostic functional mechanism fundamental to all disorders of emotion.”

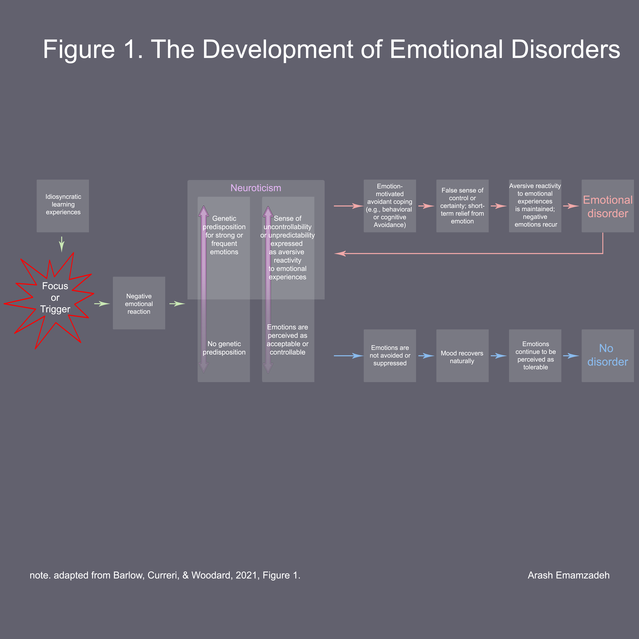

But the nature of avoidant coping and the particular emotions avoided are not the same in different people. As you can see in Figure 1, a person’s unique learning experiences (left part of the figure) interact with the trigger or focus of their emotional experiences, which then causes a particular negative emotional response. This response, depending on the individual’s genetic predisposition (i.e. their level of neuroticism), may result in an emotional disorder (or no disorder at all).

Consider phobias. Learning experiences are important in the development of phobias. For instance, one neurotic child develops a dog phobia after being bitten by a dog, whereas another neurotic child develops social phobia instead, from observing his or her parents’ anxious behavior in social situations.

What about a person who does not develop any phobia or mental illness? Does this mean the person never experienced a potential trigger? Not at all. Indeed, triggers (e.g., loss, trauma) are quite common. For instance, as Barlow et al. note, four in five people experience the intrusive thoughts of OCD, and one in three experience panic attacks, when under stress. But people with a low level of neuroticism are usually able to respond to the negative emotions they are experiencing in a healthy and adaptive way—without avoiding or suppressing their emotions. Thus, they do not develop a mental illness (see the lower pathway in Figure 1).

The small percentage of the population who do develop OCD, panic disorder, and other emotional disorders, however, respond in maladaptive ways: In these individuals, the “presence of a neurotic temperament along with early learning experiences... predispose sensitivity to some emotional triggers.” For instance, many individuals with panic disorder recall having been “sensitized” by their parents to the “dangers of unexplained physical sensations such as rapid heart rate.”

In short, differentiating between mental disorders with respect to triggers only—as the diagnostic manuals (e.g., DSM-5) do—ignores the complex similarities between these emotional disorders.

Treating Emotional Disorders

As for treatment, Barlow and colleagues have developed a cognitive behavioral intervention called the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. The protocol includes eight modules:

- Goal setting and maintaining motivation: Identifying problems and goals, discussing the motivation to change, evaluating the pros and cons of change, etc.

- Understanding emotions: Learning about emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger, guilt), and their functions, triggers, and consequences.

- Mindful emotion awareness: Increasing awareness of emotions, particularly in a present-focused and nonjudgmental way.

- Cognitive flexibility: Learning to recognize “thinking traps” (e.g., catastrophizing), and increasing cognitive flexibility by engaging in cognitive reappraisal (i.e. changing how one thinks about a situation).

- Countering emotional behaviors: Recognizing and replacing maladaptive emotion-driven behaviors (e.g., procrastination, avoidance, self-harm).

- Understanding and confronting somatic sensations: Getting repeated exposure to uncomfortable bodily sensations (e.g., rapid heart rate, dizziness) to increase tolerance of sensations.

- Emotion exposures: Getting repeated exposure to emotional triggers, such as threatening sensations and situations, in order to increase emotional tolerance.

- Recognizing accomplishments and looking to the future: Reviewing the patient’s progress and discussing future plans for maintaining the gains.

As can be seen, instead of focusing on triggers of specific psychological disorders, the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders addresses what is common to many emotional disorders: the tendency to react negatively to emotional experiences and the tendency for avoidant coping.

According to a recent review, the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders appears effective in the treatment of borderline personality disorder, anxiety, depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder (both with and without agoraphobia), obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social phobia.

LinkedIn image: Ranta Images/Shutterstock. Facebook image: Motortion Films/Shutterstock