Trauma

Preventing PTSD in COVID-19 Era

Build webs of sustainability to address trauma.

Posted April 30, 2020 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Every one of us lives now in the shadow of trauma. Uncertainty, stress, and fear are high, even for those who don't get sick. The threat of losing financial stability, health, or loved ones stalks all of us.

The next pandemic is a mental health one

A critical goal for public planners and mental health professionals in this time must be to enable as many people as possible to pass through inescapable trauma without developing post-traumatic stress disorder. It's hard to cope with trauma, but far worse is to live with a long-lasting, highly debilitating PTSD.

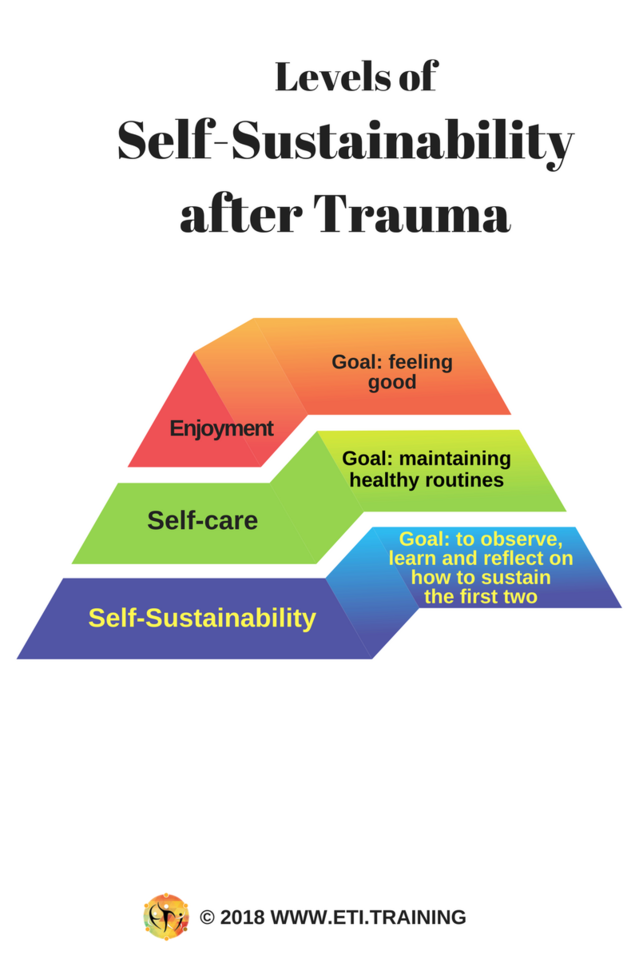

We can't prevent PTSD. But there's a lot we can do to weave webs of sustainability for individuals and communities that will greatly reduce the likelihood of widespread PTSD.

We should start with two key premises:

- Everyone is exposed to trauma, but not everyone will be traumatized;

- Individuals and communities can expand their ability to endure trauma by following sustainability plans.

In designing such plans, we must recognize that many factors affect the likelihood of any given individual becoming traumatized and developing PTSD. These include age, genetics, personal life history, physical health, personal and communal resources, and more.

A key mechanism through which these link to traumatization is self-regulation. To the extent that a factor contributes to an individual's ability to self-regulate, the individual has greater capacity to endure trauma without becoming traumatized. To the extent that it reduces capacity to self-regulate, traumatization is more likely.

What is self-regulation?

Self-regulation is the ability to manage extreme emotions (positive or negative), sensations, and thoughts. It’s a core objective of therapy, especially in trauma therapy.

All trauma survivors encounter reminders of the past. Some are able to experience these reminders without getting pushed out of their “window of tolerance,” neither hyper (too high a response) nor hypo (numb or shutdown response).

But others cannot control or escape their reactions to reminders of past trauma. For them, ongoing life is affected by ongoing reactions that can be triggered at any time. Since stress from any source sets the nervous system off for everyone, trauma survivors are even more vulnerable in response to COVID19.

Strengthening self-regulation is well-recognized as foundational in therapy in general and trauma therapy in particular. In crisis response, it is not as recognized, although there are significant data that demonstrate the need to address self-regulation among personnel who are exposed to critical incidents on an ongoing basis.

The Window of Tolerance is a term coined by Siegel (1999) to describe a balanced response to stress. When within their Window of Tolerance, trauma survivors can process thoughts and emotions, make proper judgment calls, and gain new learnings without instinctually reacting to stress.

In therapy, the goal is for clients to expand their ability to respond to triggering events in a way that makes these sensations tolerable, without throwing them off-balance (eg: hyper—too high a response or hypo—a numb or shutdown response).

Porges (2011) added an important additional concept to the Window of Tolerance, social engagement. Interaction with others is difficult in either a hyper or hypo state. But midway between the two, survivors can gain new skills and experience a full range of emotions while maintaining a sense of control. Playful social engagement is one such midway response, especially in face-to-face interaction.

From the standpoint of Porges' polyvagal theory, trauma impacts spontaneity (ability to be playful) in social engagement. Playful social engagement can help regulate stress responses and it enables survivors to expand their midzone functioning by improving their ability to self-regulate.

How can we enhance, preserve, and maintain self-regulation when stress is so prevalent? To acknowledge how challenging this is, we must recognize that the body is like a sponge that accumulates experiences. The more we have experienced chronic stress and trauma in our past, the more that our responses to stress in the present will be amplified.

Because stress and trauma affect us in complex ways, our response, to be effective, must be comprehensive. Body-based modalities are important in calming the nervous system but they are not enough. For self-regulation to be sustainable, we need to target all aspects of wellness at the same time. This must include emotional, cognitive, physical, spiritual, and social aspects of self-regulation.

A sustainability plan should include:

- Emotional regulation—connection to resources and a sense of containment—over time enhance the capacity to endure pain and experience joy.

- Cognitive regulation—using elements of self-compassion as a mix of top-down (short term) and bottom-up (longterm) impacts.

- Physical regulation—support a sense of predictability and safety by managing routines of sleep, diet, movement, and sports.

- Spiritual regulation—engaging with a sense of meaning, purpose, and self-efficacy.

- Social regulation—connecting with others (loved ones, peers, interest group peers, pets).

To the extent that we create sustainability plans, we can mitigate the likelihood of PTSD becoming a secondary pandemic.

References

Gertel-Kraybill, O. (2020 in print). Suzy and The Brain 1-2-3: What Happens in Suzy’s Brain During Trauma. Riverhouse ePress. PA, USA.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press.