Embarrassment

Video Games and Emotional States

Why your kid is addicted to Fortnite.

Posted September 3, 2018

“Oh no!!!” My son screams from his room at midnight. My wife and I don’t panic. Actually, we hardly blink or notice. You see, our son, like millions of teens all around the world, is addicted to a video game called Fortnite. Aside from the fact that one of the goals of the game is to shoot (with an automatic weapon) as many other players as possible, it is (strangely) not really a violent game - and, I have to say, it seems very fun. While there are several variants of the game out there, the main point is that you are one of 100 individuals dropped on some random island and the last one standing at the end is the winner.

My wife and I are pretty adept at being able to tell when Andrew gets shot by a sniper versus when he has just won the entire game. His emotional expressions are pretty clear and sound travels quickly in our house.

A loud, “Oh no!!! Aaaahhh!!! Aaaaaahhhh!!! No! No! No!” usually means he got sniped.

On other hand, “Yes!!!! Yes! I can’t believe it. Yes!!!” - accompanied by a big smile and sometimes a little dance - typically means that he won the round.

And so it goes. Life as a parent in 2018.

Video Games and Emotional States

One of the reasons that games like Fortnite are so addicting is that they play on the human emotional system, comprised of a long-standing set of psychological adaptations that has features going back millions of generations and across thousands of kinds of species of animals. Darwin (1872) himself was the first person to really make a strong case for the evolved function and motivational nature of the human emotion system.

In more recent history, Randy Nesse and Phoebe Ellsworth (2009), discuss the evolved nature of emotions and psychological attributes designed to motivate people to engage in certain adaptive behaviors. From their evolutionist perspective, for instance, they see some emotions as evolved responses to success regarding social opportunities (we feel happy when we are provided with success in obtaining social opportunities) and some emotions as evolved responses to failure regarding social opportunities (we feel sad and anxious when we are threatened with rejection in efforts to obtain social opportunities).

Recently, members of our research team, the New Paltz Evolutionary Psychology Lab, published a paper that examined Nesse and Ellsworth’s (2009) evolutionary model of emotions. Relevant to the discussion of Fortnite here, our study manipulated emotions in a video game context (see Guitar, Glass, Geher, & Suvak, 2018).

Using Second Life software, we designed a study that provided 50 individually run adult participants with situations that included the following:

- Physical opportunities (finding a large amount of food (or not))

- Physical threats (successfully walking across a balance beam suspended high above the ground (or falling to one’s death))

- Social opportunities (being liked by others in a virtual meeting room and obtaining VIP status (or failing to make VIP status))

- Social threats (making a lot of friends on the island (or failing to do so, leading to exile from the island))

For each of these four conceptual experiences, we manipulated things so that, based on random assignment to conditions, participants either succeeded or failed (unbeknownst to them, they actually had no control whatsoever as to the outcome!).

We asked participants to complete a brief measure of basic emotional/affective states after each outcome. These states including happiness, sadness, anxiety, anger, embarrassment, and several other items.

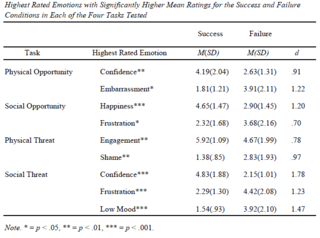

Well it turns out that manipulating these kinds of situations using an avatar-based video game paradigm is very powerful at manipulating emotions (see Table 1). Succeeding at a physical-opportunity-based task (by finding a lot of food on the island) led to confidence. Failing to find a lot of food led to embarrassment. Making it into the VIP room led to happiness. Failing to make the VIP room led to frustration. Falling off the balance beam led to a feeling of shame. And getting kicked off the island led to overall negative mood, frustration, and a major dip in confidence.

Bottom Line

Why are video games so addicting, to the point that they are wreaking havoc on humans across the globe? One reason is this: Well-designed video games have the capacity to manipulate the human motivation and emotion systems - systems that are the result of millions of years of vertebrate evolution. Is your kid playing Fortnite, or something similar, into the wee hours? Does your household include regular conversations with your child about the fact that he or she is becoming something of a video game zombie? Well guess what? Video games represent just another technological “advance” that hijacks our evolved psychology in an evolutionarily mismatched way (see Geher, 2014). We allow our technologies to advance while ignoring our evolved nature to our own peril.

This said, good luck with your next round of Fortnite, kids. I hope you win a battle royale!

********************

Special thanks to former SUNY New Paltz Teaching and Learning Center co-director and guru, Linda Smith, for working with our team on the Second Life software that was used in this research.

References

Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

Geher, G. (2014). Evolutionary Psychology 101. New York: Springer.

Guitar, A, E., Glass, D. J., Geher, G., & Suvak, M. K. (2018). Situation-specific emotional states: Testing Nesse and Ellsworth’s (2009) model of emotions for situations that arise in goal pursuit using virtual-world software. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9830-x

Nesse, R. M., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2009). Evolution, emotions, and emotional disorders. American Psychologist, 64(2), 129-139.