Personality

Character Counts in a Novel's Pages

A fun new novel illustrates various ways to show personality.

Posted June 2, 2016

A novel can be in any genre, but if the characters who people the stage, however offbeat they are, don't feel real, many readers lose interest. Plot is extremely important, of course, but if at least the major characters don't come alive, the book isn't going to be all that memorable.

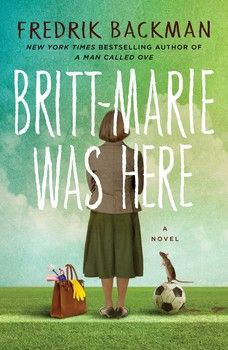

To demonstrate this point, I've chosen a few examples from a new novel, Britt-Marie Was Here by Fredrik Backman. He also wrote the bestselling A Man Called Ove, which I reviewed here. Backman, writing in Swedish and superbly translated by Henning Koch, is an author who certainly grasps the concept of making character count.

Blurbs have called this book "believable", "fanciful", and "charming". And it's all those things, and more. Backman excels at showing us an unusual person encountering a new environment and changing gradually in small ways that finally add up.

Britt-Marie, a devoted but neglected wife, gives up on her husband and moves to a small town. She encounters a bevy of amusing characters. She has an idiosyncratic way of seeing things, rigid and obsessive-compulsive, yet essentially warm-hearted and honest. She somehow finds herself coaching an untalented children's soccer team, though she is utterly unqualified in the standard ways.

No matter how Britt-Marie tries, her perceptions sound askew. For example, she's been asked to give a pep talk to "her" team before they begin playing.

"A pep talk?"

"Something encouraging," he clarifies.

Britt-Marie thinks about it for a while, then turns to the children and says with all the encouragement she can muster:

“Try not to get too dirty.”

When Britt-Marie is told by a shopkeeper that her preferred cleanser is no longer made,

Britt-Marie's eyes open wide and she makes a little gasp.

"Is . . . but how . . . is that even legal?"

"Not profitable," says Somebody [a character] with a shrug.

As if that's an answer.

"Surely people can't just behave like that?" Britt-Marie bursts out.

Here is a paragraph describing a childhood car accident that killed Britt-Marie's sister. Note how the author uses Britt-Marie's own conversational tone in the exposition:

Their mother had told Ingrid to put on her belt, because Ingrid never put her belt on, and for that exact reason Ingrid had not put it on. They were arguing. That's why they didn't see it. Britt-Marie saw it because she always put her belt on, because she wanted her mother to notice. Which she obviously never did, because Britt-Marie never had to be noticed, for the simple reason that she always did everything without having to be told.

Other details add to the whimsical nature of the tale, such as Britt-Marie's serious conversations with a rat she has befriended and to whom she feeds a Snickers bar every evening at six (with a folded napkin for wiping its feet). Britt-Marie seems not to feel sorry for herself and her objectively sad and lonely life. However, as she finds some purpose and a role in her new town, even a potential new love interest, she sees reality a bit differently than at the start. Her internal changes are not very dramatic, but they change the whole story, and in doing so, succeed in warming readers' hearts.

Copyright (c) 2016 by Susan K. Perry, author of Kylie’s Heel