Persuasion

Money on the Mind

Researchers are exploring the influence of inequality on how we behave.

Posted August 11, 2017

By Abigail Fagan

Income inequality in the United States has reached its highest peak since the Great Depression. Americans in the top 1 percent of earners currently make a staggering 40 times as much as the bottom 90 percent. Furthermore, in 1978 the top 0.1 percent of the population laid claim to 7 percent of the nation’s wealth. By 2012, that amount had increased to 22 percent. Across industrialized nations, income inequality has been linked to an array of harmful outcomes, including higher rates of debt, crime, mental illness, and even mortality.

To better understand such correlations, researchers are investigating how economic inequality might influence the behavior of those who are aware of it.

“There’s rather little understanding about how income inequality affects how individuals perceive the world,” says Gordon Brown, a professor of psychology at the University of Warwick. “We’re going to need to understand what’s happening in individual people’s heads if we’re going to understand why income inequality has negative effects on society as a whole.”

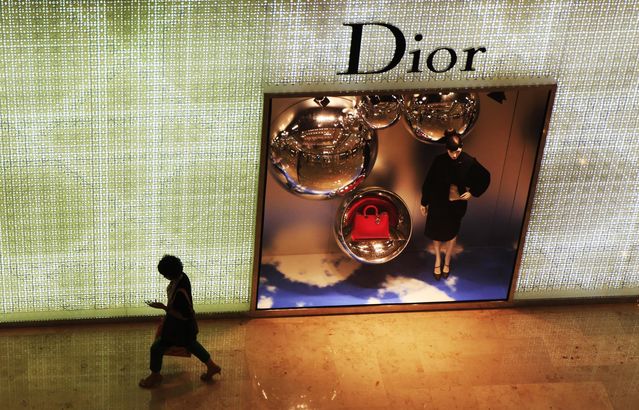

Some evidence suggests that inequality is related to thinking more about social status and to devoting more resources to climbing the social ladder, according to a study published in Psychological Science by Brown and fellow University of Warwick psychologist Lukasz Walasek. The team used a tool called Google Correlate to examine whether income inequality is associated with Internet searches for high-end items that can signal status, like a Gucci or Louis Vuitton purse. Researchers found that, compared with Google search terms used more frequently in low-inequality states, search terms that were especially popular in states with higher income inequality (such as New York, California, and Louisiana) referred more to status-relevant products.

An alternative research strategy would be to investigate purchasing habits, Brown says, but that data wouldn’t reveal anything about the behavior of the person who thinks about Louis Vuitton purses but can’t actually afford them. Internet searches may capture some of that cognitive energy. “I think people are spending more of their time and energy thinking about positional consumer goods and status” in locations with high inequality, he says, “presuming their search behavior on Google is an index of that.”

In highly unequal societies, mistrust and anxiety about social status are significantly greater than in more equal ones, according to a review paper in Social and Personality Psychology Compass. While much of the data is correlational, taken together the findings are compelling, argues Nicholas Buttrick, the paper’s co-author and a graduate student at the University of Virginia. “They come together to form a picture, looking at six or seven different measures in a bunch of different studies, that status becomes more important when income inequality is higher,” he says. And when the gap between the poor and the wealthy is especially wide, people may begin to identify more with smaller communities and less with the nation as a whole, Buttrick says.

In shifting how people with different levels of resources see one another, highly unequal gains may also drive people to make riskier choices. In a recent investigation, an experimental gambling game and Internet searches both revealed an association between high inequality and high-risk, high-reward behavior, according to research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In the gambling game, study participants were able to make decisions that were low-risk, low-reward or high-risk, high-reward. For example, they could take a bet in which they’d win 10 cents 90 percent of the time or, alternately, a bet in which they’d win 90 cents 10 percent of the time. Over many trials, their earnings could accumulate. Participants also saw how other players performed. When everyone won a similar amount of money, they showed a greater tendency to choose the low-risk, low-reward route. When the total winnings were the same, but unequally distributed—many people performed terribly while a few performed phenomenally—participants made more high-risk, high-reward bets.

One explanation is that participants compared themselves to the few gambling champions and strove to reach the same level of success, says Keith Payne, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and co-author of the study. “We have this asymmetry in who we compare ourselves to: We sort of ignore the losers and compare ourselves to the winners,” he explains. “That made people want to take whatever risks possible to win the most possible, because they wanted to catch up to those winners.”

To examine this question outside of the lab, the scientists turned to Internet searches. They found that even after controlling for median income and other variables, states with higher levels of inequality yielded more frequent searches that related to taking risks with money, such as “payday loan” or “lottery.”

Additionally, greater inequality predicted more status good-related searches, which were themselves associated with more risk-related searches. This is consistent with Payne’s theory that inequality leads people to make more risky financial decisions in order to emulate the wealth around them, according to Payne.

“Many of the problems we associate with poverty, like self-defeating decisions, are actually driven by people’s psychological reactions to inequality,” Payne says. “It has a lot to do with feeling relatively poor compared to people who have a lot more.” In his book, The Broken Ladder: How Inequality Affects the Way We Think, Live, and Die, Payne reports that while the incomes of Americans in the top 20 percent have skyrocketed over the past several decades, the average income of the bottom 60 percent of earners remains roughly the same (adjusted for inflation) as it was in the 1960s. “People are left behind, but only by comparison to those who are much wealthier,” Payne explains. The sense of being less well off than others, he suggests, is important for understanding “how changes in the economy are influencing people’s everyday life.”

Abigail Fagan is an editorial intern at Psychology Today.