Mating

What Makes Someone Physically Attracted to You?

Truth and bias in love and attraction.

Posted March 22, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

To help distract readers from current happenings, I’ve pledged myself to write something not about disease or politics. So here’s an article about love and attraction. It’s one of the happier topics in my social psychology course.

Amidst the barrage of highly specific advice from self-help magazines or love experts for how to get someone to fall for you, there are roughly five pillars of physical attraction. Many popular press articles on the causes of attraction carefully cover only a subset of these five, with an apparent focus on biology and evolution. But the causes are broader than that. And consistent with the love-is-blind ethos, each pillar is made up of one or more biases.

This article is not a how-to guide to make someone attracted to you. Instead, I briefly highlight the major causes of physical attraction according to textbook social psychology. That said, one can certainly divine or deduce a few how-to approaches from this research.

1. Beauty

There’s outer beauty, which contains the makings of classic physical attraction or chemistry, and there’s inner beauty, which refers to your traits, character, or soul. Basically, how you look or how you are can make someone attracted to you. The bias here is obvious; beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

Yes, there are widely agreed-upon aspects of beauty which can vary from culture to culture and decade to decade, in terms of who the Hollywood or Bollywood A-listers are. Yes, clothes, hairstyles, and make-up can give some advantages. But even within one culture and time period, perceptions of beauty greatly differ. It’s called having a “type.” We can even find something attractive about an individual which, when we first met them, we found unattractive (and vice versa).

The sources of our biases can be numerous, including stereotypes of groups to which a current desired partner may belong (racial, religious, occupational, and so on). Perhaps this individual reminds us of a previous partner. The TV shows and movies we watch can influence our preferences. In particular, after viewing a perfect 10 on the big screen, most of us would rate average-looking potential partners as even less attractive (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980). I should also mention that there do exist objective features of beauty, meaning that they are found to be attractive almost universally. They include kindness, facial symmetry, and (in women) a particular waist-to-hip ratio. But mostly, beauty is subjective.

2. Proximity

Let’s get this boring and non-romantic pillar out of the way. It turns out that someone is more likely to be attracted to you if you and they see each other (vs. if you never met). This is not deep. In fact, this is practically a tautology, like saying when I exited the building, I was outside.

Stated more precisely, the more often two people see each other (all things being equal), the more likely they will become attracted to each other. This is called the mere exposure effect. Some popular press authors take it too far by saying that proximity can literally trigger attraction, but the commonly cited studies here fall short of justifying that conclusion (Stalder, 2018). Proximity is necessary for true attraction but is rarely, if ever, sufficient on its own. It justifies the often asked question of a new couple: Where did you meet?

3. Similarity

Birds of a feather flock together. We are more attracted to others who are similar to us in appearance, beliefs, interests, and so on. Of course, if someone likes the same things as you, they obviously have good taste, right? Normal ego breeds such reasoning, as in imitation is the highest form of flattery. In addition, sharing views and interests will allow for more fun together, as opposed to the displeasure from hanging with someone who disagrees with you on major beliefs and finds your hobbies to be stupid.

There’s only one dimension that may support the opposites-attract idea, namely dominance-submissiveness. Dominant personality types may be more attracted to those who like being ordered around (and vice versa). But surprisingly, after interacting, these opposite individuals tend to falsely perceive each other as similar (Dryer & Horowitz, 1997).

Don’t get me wrong. You and your romantic partner are not clones of each other. You have differences. Indeed, after being with someone long enough, the differences can get on your nerves and might even break you up. But those differences are unlikely to be what sparked your attraction for each other in the early days. And you may pay more attention to the aversive differences even if they are in the minority of attributes of you and your partner.

4. You Liked Them First

This factor is probably the most complicated. Someone is more likely to be attracted to you if they first learn that you are attracted to them (Myers, 2013). Among potential processes here is again ego. If you find them attractive, they may be flattered and think you have good taste. And then once they show interest in you, you may be flattered and think they have good taste. A cycle can ensue in which interpersonal attraction grows.

Hypothetically, my well-intentioned coworker can lie to me about a woman with whom I work—say, Jane—by telling me that Jane is attracted to me when she isn’t. My subsequent interest in Jane can be noticed by Jane who then does, in fact, start to have some physical interest in me. I may see Jane’s actual interest (beyond my friend’s lies), and then I may become even more interested. We go out, and six months later, Jane and I are engaged. Is this likely? No. Is this possible? Absolutely, assuming Jane and I have some similarities between us and are at least moderately appealing to look at.

5. Non-Sexual Arousal

Lastly, brains can be tricked into mistaking our non-sexual arousal for sexual arousal. In the classic scary-suspension-bridge study, men appeared to confuse their bridge-induced physiological arousal (such as elevated heart rate and respiration) for attraction to a woman who entered the bridge (Dutton & Aron, 1974). The implication is that a scary movie or a rollercoaster ride can make for a good first date. It’s called misattribution of arousal.

In Sum

If you’re trying to make someone interested in you, here are some bottom lines. Make yourself look as good as you can (at least based on this someone’s “type”). Try to cross paths with that special someone (but avoid stalking). Bring their attention to where you and they are similar (in comedic movies, one finds the other’s Facebook page and pretends to share their hobbies). Make sure they know you’re interested (but don’t overdo it—again, no stalking). Lastly, consider a proverbial rollercoaster ride for one of your early dates.

These steps are meant as a summary of this article more than bona fide advice. Pathways to love are unique to each couple. The many self-help articles might contain a more specific piece of advice that might work for you. And once you and another become a happy couple, you become even more similar to each other and more biased toward each other in positive ways. Positive biases help you to downplay each other’s faults and underestimate the attractiveness of potential alternative partners. In fact, we typically expect such biases from our partners (Boyes & Fletcher, 2007).

Love is blind in positive ways—and not just because it can be tricked by a rollercoaster. So unlike the general goal of my blog, maybe it’s okay to let some of these biases happen. When the coronavirus social-distancing protocols end, good luck out there if you need it.

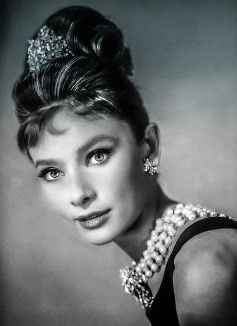

Facebook image: Goksi/Shutterstock

References

Alice D. Boyes and Garth J. O. Fletcher. “Metaperceptions of Bias in Intimate Relationships,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92 (2007): 286–306.

D. C. Dryer and Leonard M. Horowitz, “When Do Opposites Attract? Interpersonal Complementarity versus Similarity,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (1997): 592–603.

Donald G. Dutton and Arthur P. Aron, “Some Evidence for Heightened Sexual Attraction under Conditions of High Anxiety,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 30 (1974): 510–17.

Douglas T. Kenrick and Sara E. Gutierres, “Contrast Effects and Judgments of Physical Attractiveness: When Beauty Becomes a Social Problem,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38 (1980): 131–40.

David Myers, Social Psychology, 11th ed. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2013).

Daniel R. Stalder, The Power of Context: How to Manage Our Bias and Improve Our Understanding of Others (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2018).