Psychiatry

Is Integrative Psychiatry Going Mainstream?

Acknowledging the many different factors that can cause psychiatric conditions.

Posted June 2, 2023 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Integrative treatments have been growing in popularity within the field of psychiatry.

- Patients with major mental illnesses are at a substantially greater risk of chronic illness.

- New studies are finding that psychiatric illness is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction.

- Diet can influence the health of bacteria in people's guts and their mood.

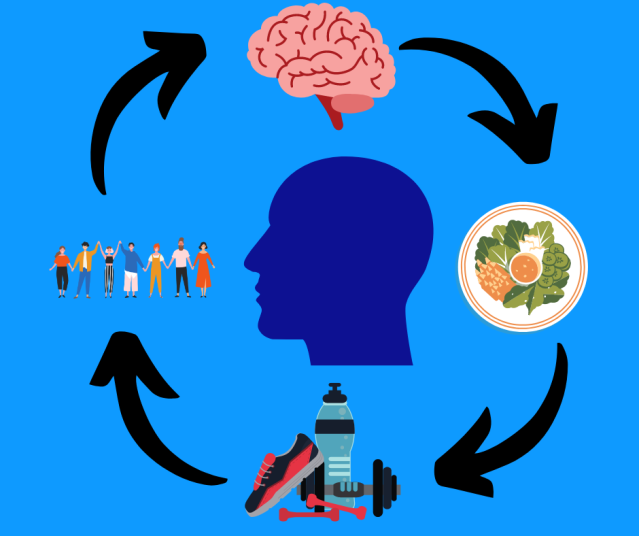

As a practitioner of mental health with an integrative approach to psychiatric treatment for over 25 years, the American Psychiatric Association’s Annual Meeting last week in San Francisco felt a bit like vindication. There is no doubt a growing acknowledgment within the field of psychiatry that psychiatric conditions are not merely psychological or neurobiological problems, and this evolution was evident in the number of sessions at the conference that focused on the role that diet, sleep, exercise, and social determinants of health play in mental illness.

Moreover, these sessions supported the idea that an integrative approach combining multiple, evidence-based therapeutic methods that include lifestyle changes, psychotherapy, and medication, among others, is key not only to promoting wellness but to treating conditions ranging from anxiety disorders to severe and persistent mental illnesses like schizophrenia. This represents a welcome sea change.

Where We Were

Integrative treatments have been growing in popularity within the field of psychiatry, but they have long taken a backseat to psychopharmacology. Just a few years ago, most of the sessions at such conferences focused mostly on clinical trials of new drugs or speculated on how drugs that were still in the preclinical phase of development were capable of targeting specific receptors or transporters. The hope was that, eventually, these drugs would usher in a world where symptoms of mental illness could be better managed or possibly even cured.

Such optimism was based on the belief that mental illnesses arise largely due to aberrations in neurotransmitter function (often described as “brain chemistry”). Consequently, it was entirely sensible to believe that the primary way to correct these aberrations was only with psychopharmacological agents. Combine this with the explosive growth in industry-sponsored studies to prove the efficacy of their drugs, and it’s no wonder why so much time was spent on these treatments.

Where We Are

The new focus on integrative medicine does not dispute that medications can be very helpful when treating mental illness. However, they are just one tool at our disposal and may not always be the only tool for every patient. Rather, we need to treat the whole and unique person, which means recognizing that the central nervous system (CNS) is in a privileged position because it is protected by the blood-brain barrier but that it is still in communication with the rest of the body. Dysfunction in the enteric, immune, or endocrine systems may contribute to dysfunction in the CNS and vice-versa.

Focusing solely on the CNS is as myopic as a cardiologist focusing solely on the heart. While it may be the organ at the… well, the heart of their practice, it does not exist in a vacuum. It is connected to a vast circulatory system that carries blood and lymph throughout the body, and cardiovascular dysfunction can lead not only to conditions like arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, or heart attacks but also to kidney disease and stroke.

Though psychiatry has traditionally stood at the intersection of psychology and neurology, there is mounting evidence that focusing exclusively on the CNS or the subjective experiences of our patients overlooks some of the underlying causes of psychiatric symptoms that we miss when we treat the brain as though it exists independently of the rest of the body. Patients with mood disorders are more likely to experience numerous non-psychiatric comorbidities, such as worsening metabolic syndrome and increased incidence of obesity, diabetes, and several other autoimmune diseases. Meanwhile, patients with major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia are not only at risk for metabolic disorders but also at a substantially greater risk of chronic illnesses, including cardiovascular disease and cancer.

In fact, one of the fascinating sessions at the annual meeting was led by Charles Marmar, Chairman of Psychiatry at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, who has been involved in research into how genetic, epigenetic, and metabolomic factors may predispose certain individuals to either be resilient or more susceptible to post-traumatic stress disorder following a traumatic event. These factors may also involve mitochondrial dysfunction, hyperactivity of the immune system, and a vast array of other issues that, at first glance, might seem completely unrelated to the pathophysiology of PTSD. On the one hand, this may allow clinicians to recognize who is most vulnerable to PTSD through simple diagnostic tests. On the other, it may also reveal the mechanisms behind PTSD and give us new insights into how to ameliorate the most debilitating symptoms.

Other sessions discussed the link between diet, gut health, and mental health. Once considered a somewhat kooky idea, it is now established science that bacteria in the gut’s microbiota break down the food that we eat and create the precursors that go on to become neurotransmitters. Moreover, research has shown that a diet dominated by processed foods and lacking in fiber and certain vital micronutrients can adversely affect the microbiome and lead to gut dysbiosis, which is associated with inflammation, chronic disease, and even mental illnesses.

Where We Are Going

This kind of research is a reminder that mental illnesses arise due to a combination of factors that include the patient’s material circumstances, diet, psychosocial environment, genetics, and biology and that the dysfunction underlying many conditions extends beyond the CNS and into the immune system and gastrointestinal tract. That the APA is giving more attention to these connections hopefully means that more mental health professionals will begin to look beyond neurotransmitter disturbances when treating their patients and may also consider interventions that involve lifestyle changes that can improve their patient’s mental health, as well as their physical health.

Additionally, broader recognition that clinicians must treat the whole person rather than just psychiatric symptoms may lead to more communication with other specialists and a more holistic understanding of psychiatric disease. Paradoxically, by looking beyond the CNS, we may discover more effective treatments and ensure our patients receive the best care possible.