Self-Esteem

10 Uncommon Tips For Addressing The Self-Esteem Paradox

The more you like yourself, the less you need to defend yourself.

Posted August 11, 2015

They drive you crazy with their tedious self-defense and self-certainty. They spend their days broadcasting their worth, but why? Is it because they think so highly of themselves that they have to crow about it, or just the opposite—they have to prove their worth to themselves because they just don’t feel it?

You make a subtle suggestion to them and they wear you out with their deflections. You’re no longer hearing from them but their inner PR agent hopped up on Red Bull, insisting that their client is exceptional and exempt from all criticism. All you said was, “you might consider doing this a little differently,” but apparently, they heard it, as “you’re a fundamentally horrible person.” And so they’re fighting tough and proud like their lives depended on it.

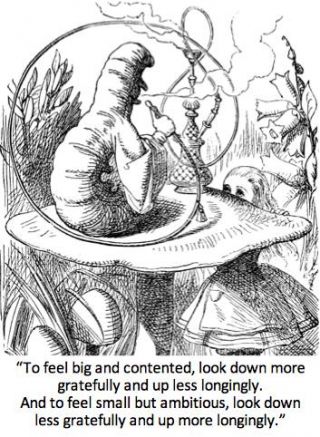

That’s the paradoxical thing about self-esteem: When we run a deficit, we talk like we’re running a surplus. It makes it hard to know whether to harden critically or soften sympathetically with these torturously proud souls so lacking in basic self-respect.

When you’re with these folks, you long for the company of people with high self-esteem. People who have a solid foundation of positive self-regard are more receptive.

Self-esteem bolstering is something we all must do, not just for ourselves but as a public service. Society runs smoother if we all can keep growing and remodeling ourselves, adjusting to, and learning from feedback and criticism.

It would be great if we could put mojo in our tap water system like fluoride. It would have to be the right variety of mojo: Calmfidence--calm confidence that you’re A-OK, not compensatory confidence covering for a lack of true confidence.

Here are some unconventional tips for bolstering healthy mojo:

1. Find where you’ve got it and spread it: As Helen Reddy sang, “Have you ever been mellow? Did you ever try?” Think of situations in which you were mellow enough to try hard to do better. Undistracted by concern about your worth, you were open to critical feedback.

Maybe it was learning from a great affirming teacher or so absorbed in some intense boot camp that you didn’t have time to think about yourself. Maybe it was when you were aching to get good at something, or when you were under intense survival pressure and you just had to be receptive. If you’ve ever been mellow enough to try your hardest, try breeding that self-calmfidence into other areas of your life.

2. Count your relative accomplishments: Nothing builds self-esteem like accomplishment, but we measure it two different ways, absolute vs. relative. Absolute accomplishment is whether you have accomplished something by popular standards; relative accomplishment is having accomplished something compared to what you were up against.

In stage banter, the performer asks, “who traveled the farthest to be here, tonight?” Ask a parallel psychological question about how far you traveled to get to here today. If you come from a dysfunctional family, a lunatic culture, or have had other challenges and setbacks along the way, factor that in when counting your accomplishments and feel proud for how far you’ve come. As the poet Philip Larkin says, “an only life can take so long to climb clear of its wrong beginnings and may never.” If you have climbed clear of wrong beginnings, that’s a huge accomplishment and should count as one.

3. Don’t blame yourself for modern times: Speaking of accomplishment, it’s harder than it used to be. Competition is more cutthroat and fewer of us have any chance of reaching the top. Many of us are employed as gears in capitalism’s massive turbine engines. We come home at the end of the day not at all sure what we actually contributed. We no longer live in what anthropologists call “task-simple societies,” where anyone but the village idiot could do all that was asked of them and fame and talent didn’t loom 100 stories above us, taunting us on social media all day. In the old days, you could be “famous among the barns,” as Dylan Thomas put it, a big fish in a small pond, enjoying your 15 people of fame. Don’t blame yourself if you aren’t huge. It’s the times.

4. Lower your expectations: When your glass is half-full consider getting a shorter glass. When our expectations are too high, we beat ourselves up. That can be motivating but it’s hard on self-esteem and why motivate yourself to do what you can’t? Get good at downshifting expectations into a lower gear for things that realistically take longer. Rehearse calmfident, credible, unapologetic explanations for why you’re still not where you aim to be, and find a few opportunities to share these explanations with others. It turns out you can often fake calmfidence until you make it.

5. Rehearse finessing criticism: There’s a vicious cycle you want to avoid--low self-esteem making you too shaky to absorb feedback, making you a slow learner, making you less accomplished and more frustrating to others who, as a result, criticize you more sharply, making your self-esteem lower.

There’s a simple way to step out of that cycle, though it takes a little practice. Practice getting good at standing corrected, standing--your dignity intact, while admitting to errors and pledging to work on them. Standing corrected is the carpenter song sung by those who can afford to remodel themselves because they’re doing so atop a solid foundation.

6. Build a healthy mutual admiration society: Yes men and women admire you no matter what, but there are two versions of no matter what. One is, no matter what you do, you’re always right, and anyone who doesn’t support your every move is a mean, vindictive jerk. The other is, no matter what you do they support your potential to keep at it and do better. The former is a short-term painkiller you don’t want to get addicted to. The latter is much better for building healthy sustainable self-esteem.

7. Get a dog: And if you want someone who loves you regardless of how hard you try, get a dog. You’ll get the self-esteem bolstering unconditional love without the distorting argument that anyone who criticizes you is a jerk. Sure, a dog will bark at anyone who attacks you, but the dog doesn’t know to bark at a co-worker who suggested that you should try harder.

8. Cultivate optimal delusion: When people claim that they’re not into kidding themselves, you can tell that they’re kidding themselves. We all kid ourselves. Being a legend in our own minds is how we wade through life’s troughs. The trick is to do it optimally--in ways that help, not hurt because the wrong delusions will steer us into dangerously deep troughs.

9. Face death because we’re all in (and out of) this together: Research in Terror Management Theory suggests something fundamental about self-esteem, exquisitely presented in this new, important book: Humans have a unique relationship with death. We can anticipate our own deaths in unprecedented detail. Knowing that no matter how grand we are, we’ll be gone in short orders is very disturbing. Arguably, a lot of our inner PR agent’s urgency to puff ourselves up is a desperate unconscious defense against knowledge of our fleeting significance. The evidence presented conversationally and convincingly in this book is well worth pouring over to understand humanity's common self-esteem management challenge.

10. Get behind something big, but not just anything: A big finding in terror management theory is that faced with death we compensate by embracing immortality campaigns, grand causes that give us hope that our significance will live on beyond us. The civil rights movement is an immortality campaign, but then so is ISIS.

It’s natural, healthy and valuable to throw yourself into an immortality campaign. It can be a real boost to healthy self-esteem, but as a public service, please pick a good one. It’s no good boosting your self-esteem with a grand plan that will steer us all into a dangerously deep trough.