Health

Inside the Psychiatric Hospital

The importance of family in providing adequate mental health care.

Posted June 4, 2014

I invited Karen Jung to write today’s blog. Karen just completed her first-year field practicum for her Social Work Master’s degree at a psychiatric hospital. Her insights are central to the theme of this blog.

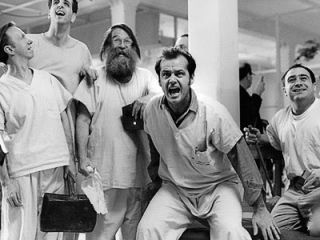

A scene from One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (1975)

After days of orientation, I still had no idea what I was getting myself into. The images of "psych wards" in my head were inspired by what I’d seen in One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest (1975) and It's Kind of a Funny Story (2010).

No one really knows what goes on in psych units. It's certainly not a place people would volunteer to visit. Mental illness carries a huge stigma in our society, eliciting negative images and stories, particularly with recent mass shootings.

Throughout my year of training, my perceptions about mental illness and mental health care changed. Now I’d suggest that people seek this opportunity because it provides a critical understanding of the elements needed for providing good mental health care.

As a social work intern, I was charged with meeting patients individually in order to complete psychosocial assessments, contacting family members and outpatient providers to obtain collateral information, and conducting family meetings.

The very first patient I met was an African-American woman in her 50’s. She had a dual diagnosis of mental illness (schizophrenia, paranoid type) and substance abuse. Her daughter, in her 30s, came in for a family meeting to assess her mother's progress. The daughter was a nurse at a psych unit at another hospital in the area. She told me that she decided to become a psych nurse because of her mother. She knew every aspect of her mother's health, including diagnosis, medication, and outpatient resources. How lucky the patient was to have such a well-informed daughter, I thought.

Patients with schizophrenia are often out-of-touch with reality; patients with bipolar disorder may downplay their manic symptoms; patients with depression may try to hide their suicide attempts. Collateral information is vital when it comes to mental health care. Family as well as outpatient providers see the patient from another lens and are able to provide information that the inpatient team can utilize to provide the best quality of care and help the patient on the road to recovery.

For every patient, I would call his/her family member and ask these questions:

- What’s been going on with the patient?

- What is the patient like at his/her best?

- Can the patient return home?

While some patients downright refused to have their family members contacted (with varying reasons), most of those I worked with agreed to provide consent when I explained that it would help them meet their treatment goals.

During the initial assessment, I would ask the patients to identify their support persons. I was surprised to learn that almost all the patients that I worked with had someone in their family -- father, mother, brother, sister, son, daughter, grandparents, even friends and neighbors – who had been helping them in the community.

Whenever I called one of these support persons to obtain information needed to help the patient, they were more than willing to help. They understood that it was important in their loved one’s treatment process. Some were truly involved in the treatment process, from day one of the onset of the patients’ illness. Some could list more than a handful of medications with correct dosage that the patient was taking. They provided such extensive information that it often seemed as though they were medical professionals.

The husband of a patient who had admitted herself to the hospital after days of hearing voices telling her to kill herself was furious when I called him. He was frustrated about his inability to help his wife, telling me that strict privacy laws prohibited him from helping her. Even as his wife’s caretaker and durable power of attorney, because the patient had yet to sign the consent form for him, he had no right to discuss her treatment information. When she finally did sign the consent form I called him. At the end of our conversation, he thanked me many times for letting him know that his wife was getting the help she needed.

This case was not uncommon. At the end of each call, I could always sense a feeling of relief and gratitude from the family members, especially when they learned their loved one was making progress.

While it can be frustrating to navigate the health care system, especially for mental health care, when done right, patients can benefit so much more in their inpatient mental health treatment process with the support of their family and community. If HIPAA laws were modified so that family could participate in the treatment more easily, patients would benefit. This was the most important lesson I learned from my field practicum. As a future social worker, I hope to continue learning about the mental health issues in our society and develop ways to make the treatment process more collaborative and fluid for the patients, family members, and care providers alike.

I also have come to shed my misperceptions on what is going on in a psychiatric hospital. A pleasant, safe environment to work in, I will certainly miss some of the patients I worked with.