Your Life as a Number

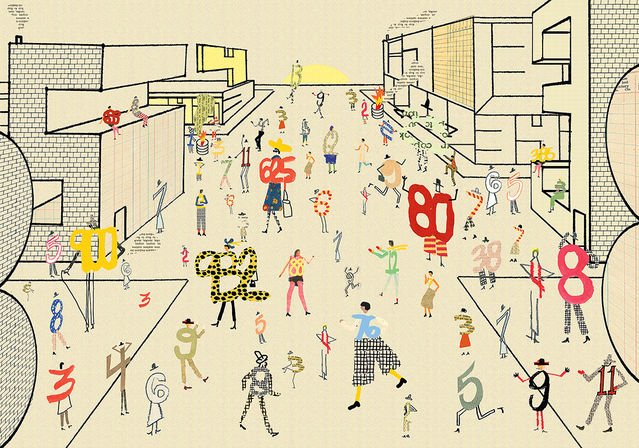

Social-credit systems may soon rate our personal worth based on finances, behavior, and friends. How will the pursuit of a top score change us?

By Jayne Williamson-Lee published June 24, 2019 - last reviewed on February 3, 2020

As you go about your day—texting friends, rating Uber drivers, searching Wikipedia—you create an immense trail of data. Every time you order from Amazon, reserve an Airbnb, or research quantum physics, you leave digital traces that the companies you patronize can access to predict your future behavior, or at least the behavior of people who share your demographic indicators. Most of us are aware of this privacy tradeoff: It’s the cost of doing business in the digital age, and it underwrites free delivery and frequent-user discounts. But at the same time, some far less transparent data brokers are hard at work sizing up your personal history and converting your tendencies into distinct scores that, without your knowledge, signal to companies—and perhaps government agencies—what kind of person you are, how much you’re worth, and how well you deserve to be treated.

Since the coming of the digital age, if not before, political commentators, science fiction writers, and consumer advocates have warned that, as data collection and analysis improved, we would each inevitably be reduced to a number—our past, quirks, and personality distilled to a single integer spit out by a machine to which we could not appeal. That day may have finally arrived, and the ramifications of this new era are just beginning to emerge. One of many concerns: Social media allow artificial intelligence systems to layer our personal connections onto our ratings. In other words, a friend or relative with poor social credit may become a liability, forcing uncomfortable decisions about whom to associate with.

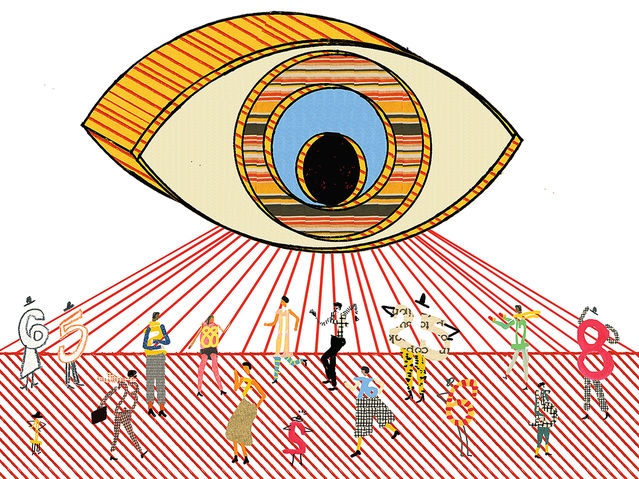

Data brokers are collecting the information we’ve knowingly and unknowingly revealed about ourselves, creating profiles of us based on demographic indicators that they can then sell to other organizations. They are participating in what Harvard Business School professor Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism,” in which companies employ systems that spy on consumers in exchange for services. Facebook, for example, provides a network to connect with family and friends in exchange for access to personal information it can use for marketing purposes.

“A surveillance society is inevitable, it’s irreversible, but more interestingly, it’s irresistible,” says Jeff Jonas, a data scientist and a board member of the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), a public interest research center in Washington, DC. “You are doing it. When you sign up for free email, the terms of use that you don’t read say that all the email data is theirs. Even if you delete your account, they can keep it for two years. This is data they can use for machine learning.”

You never see the results of the data brokers’ learning, and their clients, who make decisions based on its products, may never see you. “It’s not us as human beings that the government or institution makes decisions based on,” says Sarah Brayne, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Austin. “It’s our data doubles.”

CLV, or customer lifetime value, is one of the numbers that has been attached to us. This score grades a consumer’s potential long-term financial value to a company; it’s likely that you already have more than one. Data gathered from transactions, website interactions, customer-service exchanges, and social media profiles all influence a CLV score. Once the number is determined, its application is pretty simple: High-value customers receive better offers and faster customer service, while others are left on hold.

There is no current means of finding out your CLV score. This differentiates it from a traditional financial credit rating. And yet, even though you can check that latter number, follow tips for improving it, and even petition to fix errors, the companies that compute your credit rating won’t tell you exactly how they come up with it, citing proprietary algorithms and competitive concerns. For all the peppy commercials about tracking your score, in the end, it’s fundamentally opaque.

As institutions become more invested in representing patrons in strictly numerical form, people’s ability to put their best face forward is restricted, and that can come with a psychic cost. “Any time you make a human being look less human—voiceless, faceless, focusing less on their mental states—that is fundamentally dehumanizing,” says Adam Waytz, a social psychologist at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

China Ranks Its Billion

This ongoing experiment in impersonal human representation got its start in the United States, where the first credit rating, now commonly known as FICO, was devised in the 1950s. But the movement is reaching its fullest incarnation today in China, where the government and the private sector are moving forward with the most pervasive rating system yet imagined—a ranking of every citizen in the world’s most populous nation, based not just on economic factors but on a wide range of behavioral and social criteria as well. In the Chinese national government’s plan, which officials claim will be solidified by 2020, all individuals will be given an identity number linked to their social-credit records. Their records will include information from their transaction history, internet search reports, social contacts, and behavioral records, like whether they have ever been caught jaywalking. Businesses will also be given a “unified social-credit code.” Records eventually will be aggregated into a centralized database, though implementing a system at that scale will still require overcoming substantial technological challenges.

The social-credit plan was first revealed in a 2014 policy document and was presented as an approach to promote greater trust within Chinese society. In response to widespread concerns about corruption, financial scams, and corporate scandals—including an incident involving tainted baby formula—the Communist Party proposed a system that would “allow the trustworthy to roam freely under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.” The stated goal is to reward good behavior while punishing bad acts. Rewards for high social credit—in other words, being deemed trustworthy—may include perks like free access to gym facilities, public transportation discounts, and shorter wait times in hospitals. Punishments for low social credit could include restrictions on renting an apartment, buying a home, or enrolling a child in one’s preferred school.

Local governments in several Chinese cities are rolling out trial implementations of social rating. In Rongcheng, each resident starts with a baseline score of 1,000 and can earn additional points for “good” behavior like donating to charity or have points docked for “bad” behavior like traffic violations. Private companies such as Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial are also launching their own scoring programs. Ant’s Zhima Credit app employs data collected from over 400 million customers to generate scores for participating municipalities. Its algorithm factors in conventional credit information as well as users’ behavior, characteristics such as what car they drive and where they work, and, crucially, their social network connections. An individual’s score, then, could fluctuate based on not only his own actions but those of his friends—a brother-in-law going online to play videogames, for example, could lower it. These programs are currently on an opt-in basis, although officials are urging citizens to enroll.

Uncovering Trust

At a deeper level, credit scores and social ratings are referendums about who should be trusted. As such, they are high-tech proxies for a judgment call we have evolved over thousands of years to make face to face. Even with all of our experience, judging whether to trust someone is no easy task. Still, we understand that in most situations we can reap more benefits by working together than by going it alone, a strong incentive for mutual trust.

While it’s to our benefit to be able to detect whether people are signaling that they are trustworthy, those exact trust signals have eluded researchers, says David DeSteno, a psychologist at Northeastern University, because most have looked for distinct physical cues—a particular flash of a smile or cock of an eyebrow—when establishing trust actually involves a more complex set of repeated signals. In economic games studied in his lab, he found that, when playing in person, people were better at predicting whether a partner would be untrustworthy than when they played online and could not observe such cues. “Most of our communication online is information-sparse,” he says. “All the signals we’ve evolved to use over thousands of years to give us a better chance of predicting trust are gone.”

A social-credit rating that draws primarily on one’s online activity may fail to get at an individual’s true character, especially if data collected in one arena is applied in others. A high financial-credit score can signal to a lender that you are likely to pay back your debts, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that you should be trusted to watch someone’s children or remain faithful in marriage. “When people’s ratings are related to the same type of interaction,” DeSteno says, “they will probably have decent predictive value.” The context is stable, and judgments can be reliably applied. In a system such as Zhima’s, however, which aims to apply ratings in a range of domains, including the Baihe dating site, your financial history could torpedo your chances of finding a spouse or building other meaningful relationships.

There’s a problem with relying on reputation that’s been fixed by an external number. If it’s positive, “it gives us the sense that someone deep down is always trustworthy, while we know that most people’s moral trustworthiness shows some degree of flexibility,” he says. “If the costs or risks or benefits of interacting with someone don’t change, then reputation is a good indicator. But if suddenly something changes dramatically, it may not be.”

Is That You?

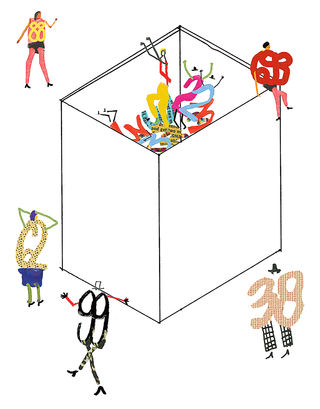

If we believe an algorithm is wrong about us, it feels unfair. On the other hand, even if a rating accurately reflects who we are, warts and all, does it mean we should be more accepting of all the potential social, legal, and financial consequences? What if we are working to change? What if we, like most people, behave differently in different contexts?

People will certainly try to game the social-credit system, DeSteno believes, because of the importance of virtue signaling in communities: “We all try to signal that we’re good, that we’re honest people. And as we have moved online, the question has become, how are we going to do that?” He cites services like ReputationManager that promise, for a fee, to clean up your virtual record and put the best face on it. “People are going to try to find ways to alter their score.”

But if there is no means of independently influencing one’s social rating, then no matter how blunt an instrument it turns out to be, Brayne says, it may simply become a fact we can’t change. The algorithms are proprietary and their data, out of our reach. The new reality: Our score is an index of our character, and we can’t stop its circulation.

“We have to believe that others are always going to make inferences about us based on the idea that our data doubles are correct,” Brayne says, and also that those inferences must be right. “They start to take for granted that this data is a pure reflection of the world.” Living in our score’s shadow could force us into a new awareness of how we present ourselves, understanding that invisible tabulators may be tracking us at any time. Which of our associates is bringing our score down? Do our purchases look responsible enough? Can we ever let our hair down and be ourselves in public?

Being yourself could become less appealing if you know that scoring systems are judging you all the time in relation to everyone you know. The launch of China’s system will give social psychologists much to consider. Broad inferences about network effects may be made as algorithms attribute the qualities of an individual’s friends to that person as well. People could become more conscious, and wary, of those they choose to surround themselves with if they know those people could have a negative impact on their social ranking. According to some reports, scores may be used to help determine whether someone can get a promotion, keep a pet, and even get high-speed internet connection. The ramifications are not hard to imagine: People whose futures are tied to the score may make cold calculations about friends’ likely numbers in an effort to make sure no one becomes a drag on their or their family’s prospects. And they may decide against friending some individuals—or whole groups of people altogether.

“If I think that information is going to be used by banks in deciding whether or not to lend to me,” Brayne imagines, “then I wouldn’t want a bank to know that I have a bunch of friends who have defaulted on their mortgage or who are low-income, because they might assume some kind of network property where I’m more likely to be poor or default on my loan, too.”

Once word gets out that a person has a low score, his social life could suffer. “Opinions might extremify, as they often do in cases of rumor and gossip,” says Nicholas DiFonzo, a psychologist at the Rochester Institute of Technology. He and his colleagues cite the “Matthew accuracy effect,” a phenomenon in which rumors about people, either negative or positive, become more extreme over time. It’s usually socially unacceptable to bring up a rumor you hear about someone to her face, especially if you don’t know her well, so people become informationally segregated. A social-credit system might engender a system of echo chambers arising spontaneously as opinions and presumptions about people circulate through networks. “What it could end up feeding into,” DiFonzo explains, “is a dynamic where, for instance, I end up not associating with you, and my opinion of you gets reinforced in a social network in which people talk about you, but you don’t get to hear what they say.”

In such a system, changing one’s fate becomes a formidable challenge. “You tend to be permanently put into a category, and you don’t have a chance to rectify or to make good with new relationships and new opportunities,” DiFonzo says. “The system is potentially unforgiving if you want to change.”

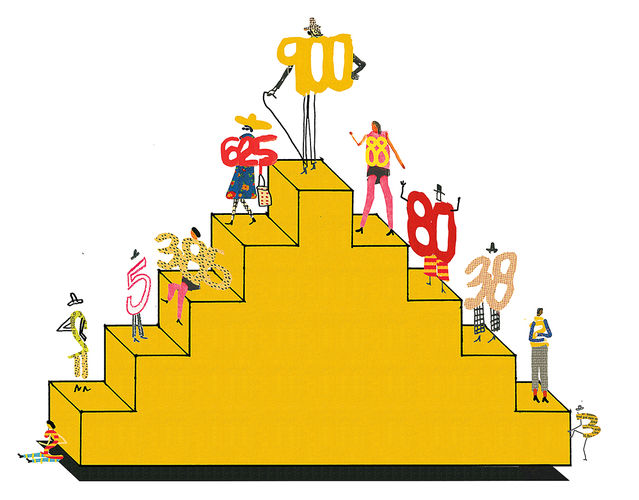

The Matthew accuracy effect is based on the Matthew effect in science, coined by Columbia University sociologist Robert Merton in 1968. The effect describes how people given some responsibility—or, in the academic context in which Merton proposed it, trusted with research funding—will tend to be given even more over time, justifiably or not. In contrast, people given less responsibility initially will be given even less over time. The effect derives its name from the passage in the Gospel of Matthew in which Jesus states, “For everyone who has will be given more, and he will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken from him.”

The Matthew effect could be powerfully reinforced with algorithmic feedback. Some people deemed “untrustworthy” in China’s pilot programs have already been sent into a downward spiral in which they are systematically denied more and more privileges until they become second-class citizens. This happened to Liu Hu, a 42-year-old journalist who was effectively blacklisted after losing a defamation case. Among other effects, he could not log into travel apps to buy train or plane tickets, his social media accounts—where he posted much of his investigative journalism—were censored and shut down, and he was put under house arrest. Despite publishing an apology and paying a fine, his status has not changed. On the other hand, as the Matthew effect proposes, high-scoring individuals could become entitled to more and more privileges over time and pass their benefits along to their children so that their offspring start life with access to the best education, medical treatment, housing, and more.

Recourse is limited for those who wish to rehabilitate their reputation with the government or with neighbors who see them get rejected for a perk because of their low score. “There are important effects on the communication structure,” DiFonzo says, “because I’m cut off from communication with people who are hearing this about me.”

People can expect their scores and ratings to affect their interactions with institutions in similar ways. CLV scores already determine how companies treat individuals and what products and offers are advertised to them based on whether they are judged to be members of high- or low-profit cohorts. That’s not the only context in which personal ratings come into play: In the health-care system, people are routinely sorted into high- and low-user categories based on their frequency of seeking care; in the criminal-justice context, growing use of data analysis may lock people into high- or low-risk categories, determining how they will be treated by law enforcement going forward. “If we’re collecting data on people in order to offer them better music recommendations on Spotify or movie recommendations on Netflix, fine; that’s one level of stakes,” Brayne says. “But if the interventions are how much the police are going to stop you, those have really direct and obvious implications for social inequality.”

At that point, system avoidance could come into play, she says. Once people come into contact with the criminal justice system, and carry that on their record, they tend to avoid institutions like hospitals and banks, as well as formal employment and education “in these really patterned ways. That type of surveillance shapes how you interact with other important institutions.”

Behavior Intervention

Social scores and rankings can also be seen as moral judgments that could affect people’s self-worth. “If you are assigned a lower social-credit score,” Waytz says, “it can make you engage in a process of self-perception in which you see yourself as less moral than others and less worthy of being human.” In this process of self-dehumanization, people may perceive themselves as being less capable of basic mental processes, such as the ability to plan or remember things or the capacity to feel pain and pleasure. In sharp contrast to a social-rating system’s stated objective of enforcing moral behavior, there is evidence that feelings of dehumanization instead could lead people to engage in more unethical behavior.

Waytz and his colleagues conducted an experiment in which they presented participants with a moral choice. They were asked to predict the outcome of a virtual coin flip. If their prediction was correct, they earned two dollars. In the neutral condition, the virtual coin flips were rigged to always be consistent with participants’ guesses. But in a different condition, the program was rigged so that participants’ guesses would be consistently wrong. They would then encounter an error on the screen telling them their prediction was correct when in fact it wasn’t. They could either report on a questionnaire that there had been a problem or claim money they hadn’t earned. Nearly half of participants chose to take the money—and in a later task, those individuals were significantly more likely to cheat again than were those who had reported the apparent problem. Critically, the “high-dishonesty” participants also reported lower human capabilities on a survey than those who had not been presented with an option to cheat. “When people behave unethically,” Waytz says, “they are more likely to dehumanize themselves, and if people dehumanize themselves, they’re also likely to behave unethically.” It’s a cycle that could be reinforced on a societal scale when a significant percentage of the population discovers they’ve been labeled less worthy of positive treatment.

Findings like Waytz’s and those cited by DeSteno point to the real possibility that social-credit systems could do more harm than good. “Whenever people live in quantified ways, they feel less human,” Waytz says, “and people treat them as more of a store of value rather than as something having real dignity.”

But a high social-credit score could also have a damaging effect on an individual, at least morally. “There’s work that shows that as people’s status goes up, they tend to be less ethical,” DeSteno says. “They will lie to their employees more or not treat them the same way—and they’ll be hypocritical in their judgments. That is, they’ll view certain kinds of transgressions as not morally objectionable if they engage in them themselves, but will still condemn other people for doing those things.”

On the other hand, high scores could theoretically direct people’s attention toward their behavior in a way that creates a sense of pride. This already plays out in the behavior of so-called credit-score fanatics who aspire to be in “the 800 club,” reflecting a standard high score in traditional financial-credit ratings. These men and women perceive an 800 as a significant status symbol. But because the FICO algorithm isn’t public, they share apparent secrets of their success with one another to help other enthusiasts try to game the system.

As behavior becomes an element of social ranking, achieving a high score could, for some, become a powerful motivator. If individuals want to reap the practical benefits and feel pride in having a high score, they may work to improve their behavior. “When people are missing pride—when they don’t feel as good about themselves—that motivates them to change their behavior to do better,” says Jessica Tracy, a psychologist at the University of British Columbia. In her research, she has found that low levels of pride are a driving factor in behavioral change. Runners feeling less confident about their progress draw on pride as an impetus to devise a plan to improve performance, and students less proud of their exam results are driven to study harder. “We can trace their increased performance across exams back to that lack of pride they initially felt,” Tracy says.

While there can be a positive relation between pride and motivation, “it has to be the right kind of pride,” Tracy says, because it is a two-sided emotion. Authentic pride is associated with feelings of confidence, accomplishment, and self-worth, while hubristic pride is associated with arrogance, grandiosity, and conceitedness. By directing people’s attention to their score and social status, as opposed to their inherent feelings of self-worth, social ranking could facilitate feelings of hubristic pride, especially if individuals constantly evaluate their rating in relation to others and seek external gratification for their accomplishments.

Research shows that people tend to be more strongly motivated to improve for intrinsic reasons—to feel better about themselves. Pushed to improve for explicitly extrinsic goals such as raising their social-credit score, Tracy says, “people actually show lower levels of performance and success. External reinforcement for good behavior is probably not going to be as effective at generating the kind of behavior that they’re looking for as a system in which people want to be good because, internally, that makes them feel good about themselves.”

Navigating social-credit systems will present individuals with novel challenges. Even the relatively transparent FICO credit scoring has had social and behavioral effects. While people can appeal their data and modify their behavior to change their score, they still must play by the system’s proprietary rules and would have difficulty navigating the financial system without participating. More sophisticated scoring algorithms that take into account aspects of life beyond the financial put even more at stake, engendering a new dimension through which institutional actors, government agencies, and even close friends can discriminate among people.

Social-credit systems threaten to perpetuate existing social stratifications by codifying and in turn validating them. They also raise the prospect that people may become more protective of their scores than of their relationships. If we become unwilling participants in such a social experiment, advocates warn, it will be crucial that we remain skeptical of schemes that could more closely connect us with authority while pushing us further out of touch with other people. “It’s going to get harder and harder to have secrets,” Jonas says. “And if you know it’s going to be hard to have secrets, then I envision two kinds of futures: One could be, everybody’s trying to be ‘normal.’ Or, people will be who they want to be, and the world will embrace diversity. That’s the future I really want.”

Jayne Williamson-Lee is a freelance science writer based in Denver.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.