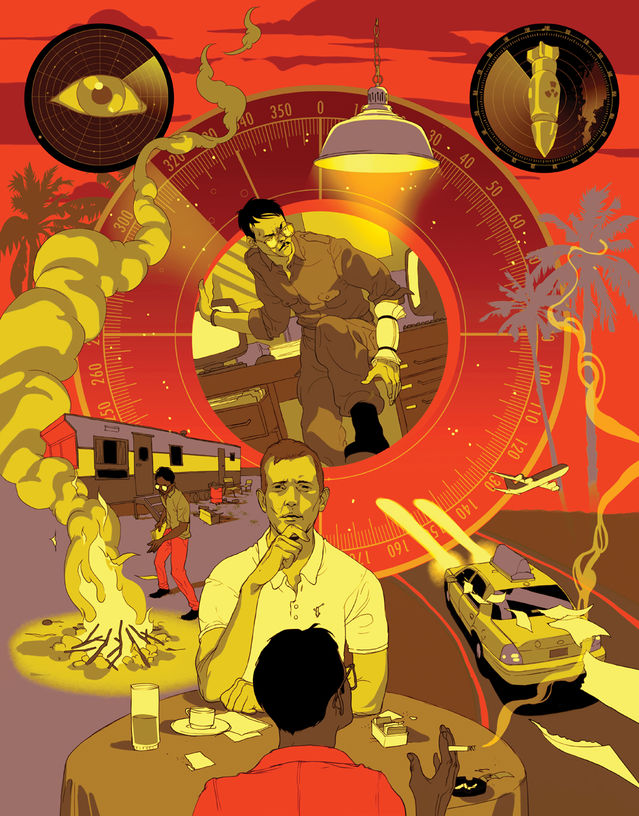

Agent Provocateur

Joe Navarro was a young FBI agent with a special expertise. He managed to trap one of the cleverest spies of the Cold War. The case gives a new meaning to counter-intelligence.

By Hara Estroff Marano published March 7, 2017 - last reviewed on May 15, 2017

It was Rod Ramsay's cockiness that first struck Joe Navarro. At 27, three years out of the army, Ramsay was living in a Tampa trailer park with his mother and flipping pancakes for not quite a living. Yet on that August day in 1988, he didn't hesitate to shower disdain on one of the two federal agents who had dropped by, just for asking some questions about his military service that he deemed too mindless for intelligent conversation.

In Germany, earlier that morning, a former U.S. Army officer, Clyde Conrad, had been arrested on suspicion of passing top-secret military plans to Russia through Hungary. For years, Conrad had been the chief document custodian at the Eighth Infantry Division based in Bad Kreuznach, West Germany, before retiring to live in the countryside with his German wife.

Navarro, an FBI agent in Tampa, and Al Eways, an Army intelligence officer down from Washington, were among the many intelligence agents fanning out across the United States that late-summer morning, interviewing anyone who might have had any knowledge about or contact with Conrad at Bad Kreuznach. Ramsay had been stationed there from 1983 to 1985. Forty-five miles from Frankfurt, the base was a critical link in the defense of the West. Its vaults held detailed documents about troop size and movements of Army and NATO forces, contingency plans for unusual events, manuals on military signaling systems, tactical nuclear weapons plans, even nuclear codes in the event that the Cold War suddenly, catastrophically heated up.

For Navarro, it was a routine visit, one of hundreds of interviews he conducted every year. No one answered the door at the trailer, but a neighbor directed the agents to a nearby tract house where Ramsay was thought to be house-sitting for a friend. After scrambling to throw on some clothes, Ramsay appeared at the door. Tall, scrawny, and jittery, he was noticeably relieved when Navarro explained that they just needed to pick his brain about the Eighth Infantry Division.

The house was small and hot, made all the more uncomfortable by the steady stream of smoke emanating from Ramsay's ever-present Marlboro. Once past their minor skirmish, Ramsay was answering questions amiably and quickly. It was hard to miss how much he enjoyed showing off what he knew—about NATO, about the strategic importance of the base, about history, about military tactics. And how he had worked in the documents section.

But when Eways got around to mentioning Clyde Conrad, there was a long pause, as if Ramsay had to stretch his memory, before he acknowledged the name. Even more striking to Navarro was the tiny tremor that seemed to pass through Ramsay's hand upon hearing Conrad's name—because it carved a visible, if vanishing, trace. The smoke rising from Ramsay's cigarette jogged a quick Z before resuming its smooth upward drift. And then it happened again.

When an hour went by and they were still talking, Navarro suggested they move the conversation to a hotel room and order lunch. There, in air-conditioned comfort, Ramsay opened up about the documents housed at the base and his life in Germany. Navarro took the opportunity to conduct a private experiment. He waited until Ramsay was well into another cigarette. What, he asked, was this guy he worked for, this Clyde Conrad, like? Another twitch and another crimp in the smoke stream.

By the end of the day, Eways was on his way back to Washington, content to leave the case of Clyde Conrad in the hands of the Germans. Navarro, however, was puzzled. Wasn't it really America's place to prosecute American spies? And what if Conrad had conscripted others to help him get documents and deliver them into enemy hands? Hadn't Eways mentioned that Conrad himself had been recruited by an Army officer before him, one who had since defected to Hungary, making Conrad a "second-generation" operator?

Largely self-schooled on the intricacies and oddities of human behavior, Navarro understood things that few people ever notice. He knew, for example, that the minuscule tremors of Ramsay's hand were not under voluntary control; they were perturbations registered by the autonomic nervous system. And weirdly, such reactions are very word-specific: Clyde Conrad was enough to rattle Ramsay. It took Navarro two years and 42 interviews to learn exactly why.

Face Time

"Most people think that interviewing is about getting a confession," says Navarro. "It's about face time, about spending so much time with an individual that they willingly reveal something to you. If you go for the confession, you get resistance. If you get people comfortable enough, they'll make all the revelations you need." Angle the questions right, never hit straight on, never hammer away at something but circle back to it another time, and sooner or later you get it all.

Navarro learned quite a few things about Ramsay that August day: That after two years he had flunked out of the Army—he failed a random urine test for marijuana, which he smoked a few times a week. And he spent "a fortune" on prostitutes; prostitution was legal in Germany, and his tastes were costly. Not only was Ramsay elastic about regulations, Navarro concluded, he enjoyed a lifestyle that required more money than he was likely earning as a sergeant. It had to come from somewhere. Conrad, for his part, was taking shape as the ultimate predator, one who knew how to target the needy.

The FBI agent also learned that Ramsay worked where the Army's operational plans for war—G-3, in military speak—are not only made and stored but also updated almost weekly. And until he failed the urine test, he had top-secret clearance to monitor them. Ramsay saw the same classified documents that Colin Powell saw.

Navarro learned, too, that Ramsay was smart. Very smart. There are not too many people who, on a cigarette break, ask a no-nonsense FBI agent his thoughts on chaos theory and the butterfly effect. And if Ramsay, although only a high-school graduate, wasn't intellectually engaged, there was no getting anything out of him, except maybe a heap of contempt.

Enemies Within

It's a long, improbable way from the quiver of a hand to a court conviction for

espionage. First Navarro had to convince his boss in the Tampa outpost that there was something worthy of pursuit, that the scrawny but whip-smart loser he had just met might be a spy—the third generation in an operation that might be continuing even after Conrad's arrest. And his suspicion was based solely on . . .smoke signals.

Then he had to muster proof, a formidable task because all the hard evidence was in the hands of the Russians, and they were not about to turn it over. Or it was in Germany, and the FBI would not authorize a visit just because some rube down in Tampa thought it was the scene of a crime.

The greatest roadblocks Navarro faced were put up by his own agency. Aside from the still-unknown extent of information compromised, the very existence of a long-standing spy ring operating out of a U.S. Army base was bound to make every intelligence agency look negligent and incompetent—and they looked a lot worse when Navarro figured out that the FBI's own Washington Field Office had failed to adequately pursue the investigation.

But it troubled Navarro that America might be exposed to grave threat— perhaps especially Navarro, a Cuban refugee ripped from his homeland at age 8, when Fidel Castro seized power. He had always harbored a keen sense of gratitude to his adopted country. "It was about my responsibility for my family to say to a nation, 'Your generosity was not misspent.'"

Off Base

Through 42 interviews, Navarro was able to document what was arguably the largest spy ring in American history. Most of the proof came from Ramsay himself, because he turned out to have a memory so exact it rendered 100 percent verifiable every revelation Navarro was able to charm out of him. Ramsay also developed an affection for Navarro, looking up to him and enjoying the mental stimulation he brought to Ramsay's disorganized life. In some ways, they became a team, the two of them against a disbelieving Washington.

When, for example, Ramsay confided that he and Conrad had rented an apartment off base to hold the vast number of documents he was borrowing to copy and sell to the Hungarians, the Army was openly mocking. "You're being used," Navarro was warned. Ramsay couldn't provide an exact address. He had gone there only on foot; he knew the route, never paid attention to street names. No personnel in Germany could confirm any such apartment, Navarro told him at one meeting, propelling Ramsay to the window in such despair he threatened to jump. Ramsay's need to be believed worked well for Navarro long after the agent was able to calm him down.

Administratively as well as psychologically, every revelation was a burden on Navarro. Each one required recounting in a report. From 7:00 to 10 :00 each morning, the agent recapitulated all he had learned the day before. A four-hour interview might generate a report of nine or 10 pages. Each report had to be filed, in multiples, before noon, in time for FBI headquarters to get it seen at the highest levels of government. There were potential implications for the Pentagon, for military bases in Europe, for the State Department, for national security, and eventually, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the White House.

Working the Angles

Early in his conversations with Ramsay, Navarro learned that Ramsay's mother was divorced and that he had had little contact with his father. It may be that Navarro came to seem something of a father figure to him—someone who was interested in him, someone he could learn from, much as he had from Conrad.

Weeks into the investigation, FBI headquarters ordered the case to be put on hold. By the time Navarro was allowed to resume it a year later, Ramsay was living in a trailer in Orlando and driving a cab. His love of books—he might consume two a day, tearing the pages out as he went, a habit he picked up from Conrad—led him to favor waiting long stretches in the cab line at the Orlando airport. It also ensured that he could barely afford to eat.

That made him especially receptive to Navarro's new plan. The agent would drive the hour and a half up from Tampa and take Ramsay to dinner at the Embassy Suites in Orlando. Then they'd head upstairs to a room readied for hours of talking, after which Navarro would drive back to Tampa.

To establish an atmosphere of ease, Navarro abandoned his FBI garb for a polo shirt and khakis. He partnered with fellow Tampa agent Terry Moody. Because Ramsay enjoyed the company of women, the presence of Moody, a Jessica Lange look-alike, would give Ramsay an extra incentive to show off all that he knew. In fact, says Navarro, "Moody's presence assured our success." Dinner was more than just a fueling necessity: It's hard to refuse a request from someone who has just fed you, Navarro knew.

Even the way they proceeded to the hotel room—the furniture strategically rearranged before Ramsay's arrival—was carefully choreographed: Navarro first, then Moody, then Ramsay, in ritualistic procession. Navarro and Moody took up preassigned positions, leaving Ramsay to relax, shoes off, on the sofa. The seats were all at angles to each other—nothing confrontational—and so placed that Navarro and Moody were at a slightly higher eye level than Ramsay. We humans are, after all, primates, and signals of dominance are important in interactions, Navarro believes. "No one," he says, "confesses to a 15-year-old." The ritual of room entry and the one- or two-inch seating-level difference were subtle, he felt, just enough to register subconsciously. Ramsay would see through anything more obvious.

Byzantine Maneuvers

Day in, day out, Navarro's biggest challenge was to conjure ways to keep Ramsay interested enough to continue talking. The minute their reports were filed, the two agents would review the growing stack of revelations and set informational goals for the day's conversation, then strategize until 4:00 P.M. about how to meet them.

Sometimes they were tasked by the Army or other agencies to get specific information: Which version of Operation Plan 4200 was copied, and when? When did specific plans go over? To whom did they go? How much was paid? What documents were the Hungarians still interested in? Interest in a specific document pertaining to troop movement, signal manuals, or tactical nuclear weapons plans meant it hadn't been seen and the information was still protected.

But most of the time they had to first find a subject Ramsay wanted to talk about and steer that into, say, nuclear codes. The Byzantine Empire. Fractal geometry. Navarro sometimes found himself on weekends scrambling to get up to speed on a subject. Knowing Ramsay's fascination with chaos theory, the agent might launch a philosophical discussion about little things affecting big things to discover some new facet of the case, like how Ramsay got documents to the secret apartment.

Navarro learned that Ramsay penetrated the innermost sanctum of the base—the Emergency Action Center, where classified communications were kept in two safes. Ramsay ingratiated himself with the guards by hanging around and relieving their excruciating boredom. He'd entertain them with coffee and conversation until, eventually, they felt comfortable leaving him in charge while they took a cigarette break—a clear violation of rules. Ramsay timed their absences. The average of seven minutes afforded him enough time to enter the safe, roll up a sleeve, roll a document around his forearm, "clip" it with a couple of rubber bands, roll down his sleeve, and wait calmly for his comrades to return.

Later, at the apartment, he’d videotape the growing stash of material—he found it faster than photocopying. He had devised an ingenious way to conceal the information. He would record it over a Disney video; even if a cassette had to be examined en route out of the country, no border guard, he was certain, would sit through Mickey’s Christmas Carol to notice the classified material buried an hour in.

Mind Games

The interviews could last for hours. One went on for 12 hours straight. “It was mind-bending,” Navarro recalls, “because I had to remember all the facts. I’d take a bathroom break and write things down quickly.”

Corroborating the information Ramsay divulged was critical. It had to be bulletproof in court. “I was concerned with how we would prove everything,” recalls Navarro. Could he and Moody get Ramsay to repeat something he had told them days or weeks before in the exact same way? “We needed to test his memory to demonstrate that he was a reliable witness and we hadn’t inadvertently supplied him with information.”

The agents constructed puzzle games of remembering. Out of the blue, they might hand Ramsay a blank sheet of paper and challenge him to remember where some specific individual sat, and he would draw that. Then they’d ask him to expand on the information. What office was next door? Where were the doors? Where were the copy machines? Pretty soon Ramsay was diagramming the entire G-3 plans section. In 42 interviews and 127 pages of Ramsay’s admissions, Navarro and Moody never found one discrepancy in his retelling.

In Europe, Ramsay had had occasion to accompany Conrad from Bad Kreuznach to Austria. Conrad was teaching him the spy trade and, during the decades of the Cold War, Vienna was the spy capital of the world. It was there that they sometimes passed off documents to the Hungarians, who then furnished them to the Russians. In his conversations with Navarro, Ramsay recalled encounters at a Wienerwald restaurant near the main train station and described the place from memory. When Navarro later went to Austria to corroborate the information so he could present it to a jury as evidence of Ramsay’s believability, he found the descriptions so exact that he could practically smell Ramsay’s cigarette smoke.

During another interview, Ramsay recalled a U.S.-French operational plan in phenomenal detail. Not only did he cite a section in what later proved to be word-for-word accuracy, he also specified the page and the position of the section on the page. Army brass thought it hilarious that Navarro actually believed Ramsay—until they got their hands on the document. Then they began worrying about what else the guy knew, because everything was in his head in photographic detail and it was all highly marketable.

The piece de resistance, however, was not in his head. That was “the biscuit,” as it's known in military ops, a credit card–like piece of plastic printed in code, authorizing a nuclear launch. The President of the United States carries one at all times. Ramsay also had carried one in his wallet, a parting gift to himself when he left Bad Kreuznach—perhaps a self-appropriated annuity policy—but he burned it after first meeting Navarro. Ramsay said that he buried the ashes behind his mother’s trailer because he thought the agent might be back the next day with a search warrant. The FBI was able to confirm Ramsay's familiarity with the biscuit, something he should never have seen.

Extreme Show-and-Tell

Once Washington learned that Ramsay had come into possession of a nuclear authenticator, the interviewing took on a new urgency. Navarro and Moody were determined to find out who else might have been involved in espionage. But naming others was the one area where Ramsay was defiantly silent. If he wouldn’t offer up the information, Navarro would have to find a way to extract it.

And so Navarro devised what might be the ultimate game of show-and-tell. He would present a series of names, the names of everyone who had worked in the document vault during Ramsay’s time at Bad Kreuznach. The agent was counting not on verbal response but on what his colleagues called, not without admiration, “that voodoo shit”—his expertise at reading flickers of facial demeanor typically generated without conscious awareness and often referred to as “tells.”

A colleague dispatched to get from the Army a list of anyone known to have worked with Ramsay came back with 32 names. Navarro printed each one in big letters on a 3-by-5 index card and, counting on Ramsay’s intellectual competitiveness, challenged him to test his recall. Navarro would flash the card just long enough for Ramsay to read the name—perhaps a second—and then Ramsay was to utter the first personality descriptor that came to mind. Asshole, nice guy—that sort of thing. Sitting barely two feet away, Navarro positioned himself more to look than to listen and focused closely on Ramsay’s eyes. Twice Ramsay’s pupils constricted—an automatic response to threat or concern.

Days later, after the Army provided files on the two men implicated, Navarro asked Ramsay if he thought anyone else might be talking to the Feds. Then he slapped down photos of the two men. An angry Ramsay described in detail exactly how they had helped him get documents out of the vault. Navarro's trick, yes, but one approved by the courts.

Human Dilemmas

As if the two years of interviewing didn’t present enough hurdles, Navarro and Moody had to endure a number of articles about the case that somehow found their way to major news outlets. In 1989, for example, The New York Times reported on the arrest of Conrad and speculated that there were Army men formerly stationed in Bad Kreuznach but now back on U.S. soil who had also been involved—information calculated to spook Ramsay. “People leak stuff all the time when they want to undermine something,” explains Navarro. “There were innumerable leaks on this case, done with the intention, I believe, of derailing further inquiry.”

After all, Navarro’s ability to get information from Ramsay rested not only on his behavioral “voodoo” but on another delicate commodity—good will. At any time, Ramsay was free to hire a lawyer and stop talking, or to run. He always had with him something of great value to the enemy: His photographic memory alone contained enough information for the Russians to quickly demolish the defenses of the West.

Compounding the pressure Navarro felt was the fracturing of the Soviet empire. In November 1989, the Berlin Wall came tumbling down. The Warsaw Pact was about to become history. While many in the East and West were cheering, the intelligence community was not. They were terrified that the KGB would initiate hostilities to prevent the dissolution of the Soviet bloc. There was precedent: It was hard to forget the Prague Spring of 1968, when, assisted by the KGB, the Soviet army rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the reforms initiated by Alexander Dubcek. And there was current reality: “There were vocal forces in East Germany wanting the Soviets to come in and rescue the country,” Navarro recalls. “No one knew which way it would go.”

Then, too, there was the mounting dissonance in Navarro’s own head. Yes, it was morally just to pursue a man who had put America in grave danger, but there was also the lying—to Ramsay’s mother, who was calling Navarro several times a week to make sure her son wasn’t headed for trouble, and to Ramsay himself. “I told him, ‘You’ve got to understand. I’m the investigator. Arrests are not up to the investigator. Arrests are up to the U.S. Attorney.’ I could see him grasping on to that, where as any attorney he might have hired would have said, ‘Shut up, and come and talk to me.’”

Does Joe Know?

In June 1990, Navarro was able to persuade Washington to authorize the arrest of Roderick Ramsay. Normally, agents are happy to cuff the bad guy. But both Moody and Navarro declined to take part. They asked Ramsay to come down to Tampa for a conversation. When he walked into the hotel suite they had reserved, he was dressed, ironically, almost exactly like Navarro—in khakis, a salmon-colored polo shirt, and penny loafers. As he exited the hotel—he had to get back to Orlando for his taxi shift— an agent approached him and displayed his badge. Ramsay offered no resistance. He did, however, have one question: “Does Joe Navarro know about this?”

Navarro and Moody witnessed the scene from the hotel suite, but they found nothing to celebrate. “I didn’t want to grab drinks with anybody,” Navarro recalls. “There was nothing to high-five. I saw only multiple tragedies: a mother with a son who had been a problem his whole life. A very intelligent mind wasted. And the horrific damage done to the United States”— although at the time of the arrest the full scope of betrayal was as yet unknown.

.

After Ramsay left Bad Kreuznach, Conrad had recruited yet another generation—a typist in the G-3 typing pool. During her tenure, top secrets were passed to the enemy even before the American commanders saw them.

For all of his wiles, Ramsay made a lot less money from the sale of secrets than anyone might have imagined. Before his arrest, Conrad had stashed away millions, largely in gold coins. Ramsay got no more than $20,000. He did it, mostly, for the thrill, the sheer stimulation. As he once told Navarro, “If I had met you earlier in my life, I might have turned out differently.” It was a case, says Navarro, of “learned sociopathy.”

Roderick James Ramsay was tried and convicted of espionage in 1991. He was sentenced to 36 years in prison. After serving nearly 23 of them, he was released in 2013.

To learn more about Joe Navarro and the spy ring mentioned in this article, please see Three Minutes to Doomsday, which will be released in April.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the the rest of the latest issue.