Can One Man Save American Business?

Hitendra Wadhwa teaches current and future executives how to breathe. He believes that self-regulation can achieve what market regulation cannot—great business leadership.

By Dorian Rolston published July 2, 2013 - last reviewed on December 21, 2020

"You're going to hear a lot of weird shit today,"a Columbia University business student announced as his peers filed into the weekend retreat that tops off one of the school's most popular courses, Personal Leadership and Success. "Just leave your judgment at the door."

Ever since 2009—shortly after the housing market collapsed, the finance industry was shaken by its own recklessness, and the economy descended into recession—Hitendra Wadhwa has been teaching the wildly overenrolled course to the current and future elite of American business. The award-winning professor promises not how to make a living but how to live.

Mumbai-born, Bollywood-handsome, trained by spiritual gurus in India, as well as by management scholars at MIT, and experienced in American business, six-foot-four Wadhwa straddles two world views: "the material advancement America has been leading" and "the spiritual wealth that has existed in certain other cultures over time," especially in India. The two are not at odds with each other, he insists. "It's important to have both. One trains you on mastering your inner life, the other on mastering your outer life."

The basic claim Wadhwa makes is that inner life matters—increasingly—in business. "Your thoughts, your beliefs, your inner hungers, your emotions, your values, your motivations are all inner-life issues lost from view in the typical focus of business and management—but they nevertheless spill out in attitudes and get played out in behavior," he tells leaders-to-be.

Crystallizing mind-sets into missions, articulating purpose into goals, and pursuing them according to consciously explored values not only infuses executives with authenticity but can make innovation and economic growth instruments of good for all of society. Unfortunately, Wadhwa finds, although the business climate is increasingly complex, it currently operates on too narrow a spectrum of the human psyche, limiting the resources leaders draw on and the positive impact they can have on markets and other measures of societal well-being.

Drawing on findings in neuroscience and psychology—as well as on the personal trials of such great leaders as Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill—Wadhwa schools students on what science knows about inner life. But at the retreat, science cedes to storytelling, and participants get to actually engage in introspection—some for the first time in their overachieving, Ivy-schooled, blue-chip lives.

Wadhwa asks students to recall "crucible moments." For those whose lives have been defined strictly by visible achievements, "there's a tremendous stirring that happens," he says, calling storytelling "powerful for your own awareness about your values and what matters to you."

"No one broke my heart the way that firm did," one woman reveals to the group. She cursed not being offered a job by McKinsey & Company, the premier management consulting firm said to have groomed more of America's CEOs than any other company. So shaken was she by the rejection that "I actually wanted to die. I would stare at the knife in my kitchen." Now she could look only at the retreat-center floor. "I couldn't believe that one person had such power over me," she confided. "The things that we overachievers let define us, we can't let define us."

Leaning against the back wall of the room, hands folded across his chest, Wadhwa looks pleased. The deeper the students probe, the more they seem to penetrate layers of gilded identity. "They live in a world of outer achievement," he says of the students, driven by strictly "short-term, material, self-centered pursuits."

Wadhwa contends that business chiefs must lead as much from within as from without, move from Masters of the Universe to Masters of Themselves. You can't fully direct the outer environment until you can direct your internal environment, he believes. "So I pose the question, which kind of leader do you want to be?"

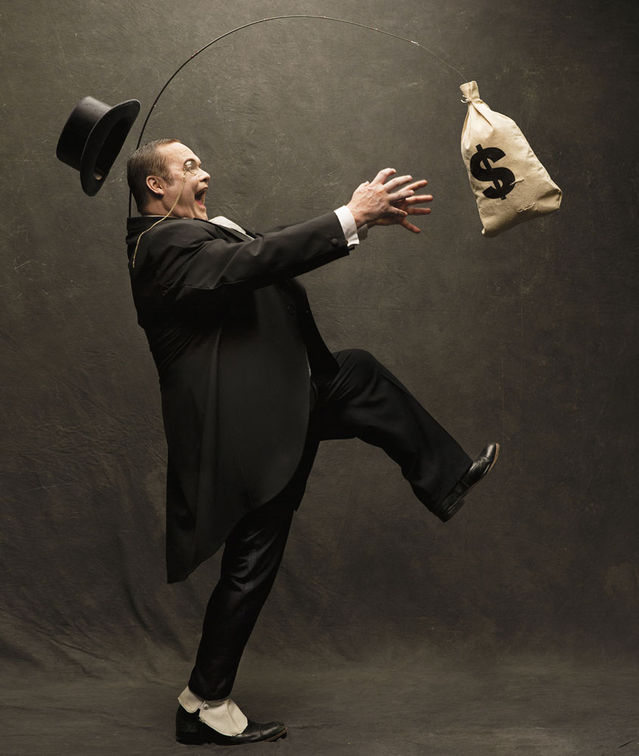

HITENDRA WADHWA wants companies to value the whole person, not just the business person.

"Back straight, shoulders arched," Wadhwa eventually commands softly. The screen at the front of the retreat center displays a businessman seated in a lotus posture on a crisp $1 bill. As the professor leads the group through meditation exercises, he explains that a bent spine obstructs the flow of energy that helps usher in self-awareness, from which leadership begins.

Wadhwa is not the first to teach "soft skills" to business students or to claim that personal values are essential in the corporate world. Stanford Business School began offering Interpersonal Dynamics, a course on emotional intelligence that students know as Touchy Feely, as early as 1966. Since then, similar courses have been added at many B schools.

"Authentic leadership starts from within and then moves without," insists William George, professor of management practice at Harvard. George has studied hundreds of leaders whose failures, he contends, stem not from lack of intelligence but from a dearth of self-awareness. Leaders, he finds, need to be "able to understand external pressures and have the resilience to stay grounded," to resist "pleasing the stock market, their own compensation, power, fame."

Even when Wadhwa joined the marketing division of Columbia Business School a decade ago, "the idea that self-awareness and emotional intelligence matter was not new," observes Joel Brockner, chair of the management division. "But what Hitendra is doing—the depth to which he is taking it—certainly is new." The storytelling is transformational, Wadhwa believes. It actually flips the participants inside out.

Wadhwa sees large gaps in the inner life of today's business heads. An obsession with material rewards has replaced the intrinsic motivation that comes from personal leadership. Behavioral economist Dan Ariely concurs. A professor of psychology at Duke University, he contends that the current incentive system of business is predicated on an oversimplified view of human nature. "The logic is that you put a ton of money in someone's path and that by thinking about the money they will somehow do a better job." In fact, Ariely has found just the opposite to be true: Extrinsic motivation is no match for intrinsic motivation. His studies have shown that, after a certain point, those who are best compensated turn in the worst performances.

If leaders are blind to the influence of incentive structures on their own psyches, so are they unaware of themselves in general.As Ariely has reported in Predictably Irrational, people typically downplay the effects of states of arousal—induced, say, by anger or even hunger—although these conditions disrupt their thinking even when they remain outwardly calm. "If you just cultivate more of a sense of self," Wadhwa says, "you will be less likely to be duped by forces that are all around us. It's very important to create buffers between ourselves and our environment." For him, the ultimate buffer is self-awareness.

An overfocus on financial outcomes not only sacrifices the need for personal meaning but thwarts societal contributions. According to a recent survey by the business magazine McKinsey Quarterly, a majority of executives worldwide confess to having a responsibility to—but short-shrifting—"the broader public good." Unlike loopholes, which may be closed by new rules, these gaps represent holes in the psyche that require new values. "Change won't be something we do through purely legislative measures," Wadhwa says. "It's got to be psychological."

Merged Cultures

As a boy in India, Wadhwa explored various spiritual traditions, teaching himself meditation by age 10 and yoga a year later. "I was drawn to the contemplative questions about the secrets of success, happiness, fulfillment, and the meaning of life," he recalls. Seeking a way to infuse a broader consciousness into daily life, he discovered the teachings of Paramahansa Yogananda, among the first to bring yoga to the West (Mark Twain's daughter was a devotee).

After graduating with honors in mathematics from the University of Delhi, Wadhwa left for the U.S. in 1988. He earned an MBA and a Ph.D. in management from MIT, then joined McKinsey, counseling America's senior executives on business strategy.

In three years there, he saw his colleagues, who were ostensibly monitoring the missteps of the business world, succumbing to them just the same. "People were writing on what's broken in business and how to fix it," he recalls. "But the level of analysis, identification of problems, and search for solutions was often not deep enough."

His faith in capitalism undimmed, Wadhwa went on to launch two marketing companies. The first, Paramark, was eventually acquired. The second, Delphinity, founded in 2002, has counted J.P. Morgan, Chase, American Express, and Best Buy among its clients; it remains active under Wadhwa's ownership.

But amalgamating two cultures proved challenging. Wadhwa struggled to maintain the pace of American business—constantly setting, striking, then resetting targets. He felt stifled by the action-oriented orthodoxy, which he believes is too outcome-driven, "too focused on incremental ideas and their execution." The relentless demands "handcuffed" him, he says, and drowned out moments of reflection.

He joined Columbia part-time in 2003 and taught marketing strategies. But he soon found that the concerns of many students echoed his own—how to reconcile business and personal values.

In 2007, he began teaching full-time and a few years later founded the Institute for Personal Leadership. Affiliated with Columbia, the institute offers three-month-long online seminars to executives worldwide. Wadhwa is now expanding his teaching into an online network of personal leadership that, he believes, can create a new model of business education.

Personal Profits

"If you have to choose between two models of the company, one only about profit and the other about profit but also about other stakeholders, which would you choose?" asks Tom Donaldson, a professor of ethics and law at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business who has monitored how executives worldwide answer. Thirty to 40 percent of those in the U.S. choose profit only. By contrast, only about 10 percent in Japan do. "In the last 10 years," Donaldson observes, "there's been a growing concern among business academics asking fundamental questions about what the corporation is really about."

The vote of American business leaders is reflected in the mission statements of many companies, observes Gerald Davis, professor of management at the University of Michigan's Ross School of Business: "We exist to create value for our share owners on a long-term basis by building a business that enhances The Coca-Cola Company's trademarks." "Sara Lee Corporation's...primary purpose is to create long-term stockholder value."

In pledging themselves to their shareholders, today's leaders have essentially adopted the culture of Wall Street, says Karen Ho, a professor of anthropology at the University of Minnesota. Contributions are measured, and rewards doled out, strictly according to share price fluctuations. In 1996, Ho was working toward a Ph.D. at Princeton when she decided to study Wall Street from the inside. She landed a job as an internal management consultant at Bankers Trust in New York. Six months later her department was eliminated. As she reported in Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street, "the rationale was that we were a fixed expense that detracted from shareholder value."

Today executives across all sectors distill their raison d'etre to serving those with shares while ignoring the interests of those without—most workers, customers, society at large. But it wasn't always the case. Leaders in the past have balanced many constituencies. During the Depression, for example, General Electric refused to fire a single worker. But by 1981, led by "Neutron Jack" Welch, the company began cutting manpower, reducing payroll by 25 percent—although Welch later had a change of heart and called shareholder value "the dumbest idea in the world."

"Once the pressure exists to maximize profitability and to compensate people to reflect stock price," says economist Marina Whitman, a professor of business administration and public policy at Ross, "the individuals in the middle of it start to think of the signals in more personal ways." Ballooning levels of executive pay not only represent a leader's performance but create a sense of power, self-worth, and social status. "You go from economics to psychology," Whitman observes.

Prestige can be considered a type of economic good, adds psychologist Jonathan Haidt, a professor of ethical leadership at NYU's Stern School of Business. But unlike money, prestige is in limited supply. "We can all have more money, but only 1 percent of us can be in the top 1 percent," he points out. The result is that executives jockey for position, taking risks to outdo one another in a competition for status.

The competition is fiercest on Wall Street, where Ho saw the leadership subscribe to market fundamentalism, a belief that as profits are secured, all else will follow—jobs, industry health, income equality, even the integrity of the environment. Bankers indeed have come to see their approach as noble. Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein notably called it "doing God's work."

But "God's work" is increasingly turning the public off. According to polls conducted by GlobeScan, support for capitalism and free enterprise declined from 80 percent in 2002 to 59 percent in 2010, and the public holds business leadership partly responsible. At Harvard in 2012, the Kennedy School's National Leadership Index found only a "moderate amount" of confidence in executives and "not much" in those in finance.

The pressure to demonstrate profits can not only subsume all other values, it can up the appeal of questionable methods. Last fall, another case of insider trading came before the courts. Implicated was the former chief executive of the very company considered the wellspring of business acumen, the company hailed as the "best CEO launch pad" in the country—McKinsey.

"Don't get me wrong," says Tim Kasser, chair of psychology at Knox College, "I think there are some bad people in corporate America. The real problem is that it's a bad culture. It activates and encourages those materialistic values, and ends up suppressing more intrinsic, pro-social, and maybe spiritual values."

Kasser sampled a couple thousand people from 15 nations. He asked them what they value most and what they value least. Physical Health and Safety cluster together. Hedonism and Spirituality are as far apart in the results as it's possible to get.

The value most opposite Financial Success is Community. "It's relatively difficult for people to simultaneously focus on the desire for making money and enhancing profit at the same time as on people outside of their in-group," says Kasser. In other words, people struggle to simultaneously value greed and generosity. Activating one value also activates other values clustered with it, and depresses those values opposed to it.

As Dan Ariely puts it, and his own studies show, "once market norms enter, social norms leave." Financial success, he says, "crowds out the value of a social good." Merely thinking about money, he finds, constricts people's concerns and orients them toward themselves. They become "more self-reliant and less willing to ask for help, and less willing to help others." Yet corporate America is unaware of these psychological forces, which are at its heart, he says. "People study too much economics. So money becomes the only incentive people think about."

"You can see the punch line coming here, right?" Kasser goads. "To the extent that a business leader becomes increasingly focused on maximizing profit, there's a corresponding decline in focus on the good of the community." In other words, "It's completely predictable that you have things like Enron and all the scandals where people do things that hurt others."

"These are well-intentioned people who under strain and stress just break down a little bit—get a little bit more angry, less patient, less considerate of others," Wadhwa says wistfully. "They all have that inner voice, which is always there, but often what is lacking in their execution is the self-discipline."

In contrast, Wadhwa points to Southwest Airlines, the country's largest low-cost airline and the most consistently profitable airline over the past 40 years. It was founded and until recently led by Herb Kelleher, whose clear sense of purpose reversed the usual equation of focusing on the betterment of investors. Kelleher believed it was most important to make his own people happy in the expectation that all 46,000-plus of them would make customers happy, so they would keep returning, which would keep the company profitable and shareholders happy. "People are inspired by meaning," says Wadhwa. "When you create an organization whose culture is larger than any individual sense of meaning, then you can create more natural, more intrinsic levels of motivation. People feel a sense of purpose to their work."

A Good Cheat Code

This course, Wadhwa acknowledges, is only "a one-time immersive experience." Can the gains endure?

"The most important thing was doing the work of trying to understand what's important to me," says one alumnus of the executive MBA program, who works in operations at a Wall Street investment bank. Defining her values enabled her to "step back from the day-to-day frantic life that everyone is subject to. Running towards goals, you never sit down and really think about if they're yours or just part of what you get packaged with as you go through your career." What persists is an awareness of whether the decisions she makes are "based on what's really important to me and the sense to pull myself away from the treadmill that everyone else is running on."

The apparent disparity between the "soft skills of self-mastery" and the "hard skills of investing, accounting, and strategy" that drew another student to the course confront him every day as general manager for a large publicly traded drilling company. He oversees a $100 million division with over 400 workers just as the industry has begun to erode. "My bosses are hammering shareholder value over all else," he confides. "But I'm seeing the long-term picture, where profit is not in conflict with quality of life and job retention and satisfaction." He considers the self-awareness instilled by the course "a competitive advantage, like playing a Nintendo game with the cheat codes."

Kasser believes business schools must train leaders to change the culture from within. Wharton's Tom Donaldson agrees. "The mind-set in modern business is sparked by what we teach in universities and business schools. At some level, he adds, "we all know there's something wrong with the current model. But that's not what we teach. It's almost like the line out of The Godfather: 'It's business. It's just business.'"

The socialization process is such that early in graduate school future business leaders go numb to nonfinancial concerns. "You can see it," says Rodrigo Canales, assistant professor of organizational behavior at Yale. "As soon as you ask students 'What business decision would you make in this moment?' all human values drop to the background. They think there's a different mind-set you need to use and that it's only a technical decision." Surveys by the Aspen Institute show that in their first year, 43 percent of male enrollees aim to make a contribution to society; by their second, only 29 percent do.

It's "the thrill of joining the social and economic elite," observes psychologist Geoffrey Miller, a visiting professor at NYU's Stern School. "They come in typically with five to eight years of business experience, they meet other bright and ambitious carefully selected students, they think they've gotten there through purely meritocratic selection, so they deserve to be masters of the universe.

"That means everybody else who isn't a shareholder is a loser, including 99 percent of consumers and most of the company's workers," Miller adds. "It does tend to instill a very predatory attitude toward other people and toward society."

The irony, Tim Kasser finds, is that materialistic values not only lessen concern for others, they undermine job performance and depress well-being.

Wadhwa's course, or something like it, may be just what American business needs—less number-crunching, more introspection. It's just that a few lectures and a retreat are not enough against the pull of everyday business environments.

"Every community has its own culture," he says. "I was a different person in graduate school at MIT, at McKinsey, in Silicon Valley. Each culture has a different mind-set and beliefs that by osmosis get assimilated into your own self: what is considered to be cool or uncool, the definition of a good life. All these things silently shape our behaviors and choices."

With that realization, Wadhwa is building an international online peer-to-peer platform for his graduates—now numbering over 2,000—to help them integrate personal leadership into their daily lives and, together, to serve as a critical mass for change. "Part of the journey of reengineering business is about aligning people more with their inner voice than with the noise going on outside them," he says. "It is very rare for someone to be able to maintain the self-awareness and self-discipline to step back on his own."

Resisting the Pressure Cooker

Hitendra Wadhwa identifies five pillars of personal leadership. The first pillar is purpose. Anchored in values, purpose not only drives leaders forward from within but allows them to escape the hedonic treadmill that constantly escalates demands for the outer markings of success yet is ultimately unfulfilling. Happiness is measured by progress, not paycheck.

Wisdom, the second pillar, requires harnessing emotions, thoughts, and beliefs so that at critical moments, emotions don't hijack the more rational centers of the brain.

Meditation is just one technique to monitor thoughts and feelings so they can be consciously deployed. Along with solitude, it helps create self-awareness, the third pillar. Discovering one's inner core is both empowering and freeing for leaders, Wadhwa finds: Business success is no longer conditional on the evaluations of others. Leaders instead can focus attention on what matters most.

The fourth pillar, love, is an expansion of the sense of self that enables leaders to share in the joys of others. Finding success in the success of others encourages leaders to develop their people to make them successful. There's an important return on investment, says Wadhwa. "People will in turn be motivated to have you succeed at your own goals."

Growth is the fifth pillar. "One of the core aspects of leadership is the capacity to be ever-renewing," says Wadhwa. It involves moving toward the ideal self that everyone harbors but which is often sacrificed as businesses leaders are swept along by the endless stream of pressure from without. And it encourages leaders to course-correct failure as a stepping-stone toward learning and success.