Intelligence

Why the Brain Is Shrinking, and What It Means for Us

Part 2: How could we have accomplished so much with our shrinking brains?

Posted June 17, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Brain size is of little scientific value in explaining how intelligent an individual human is.

- In recent history, when humans have scaled the heights of cognitive innovation, our brains have actually shrunk.

- Having fewer neurons, along with less body mass, means lower energy costs. This means less time finding food.

This post is Part 2 of a series on brain size and intelligence (Part 1 is here).

As I have written previously, there is little evidence that bigger brains necessarily make an animal smarter, both in terms of the relative size across species, as well as for individuals within a species. This latter comparison includes us: brain size and indeed the size of brain components is of little if any scientific value in explaining and predicting how intelligent an individual human is.

At the species level, many people are familiar with the idea that humans have especially big brains. It is true that, based on our body size, our brains are bigger than would be expected. They have expanded remarkably over evolutionary time. Human brains have tripled in size compared to four million years ago. The brains of human ancestors at that time were literally pint-sized (about 16 ounces in volume), while today we have almost a pitcher full of neurons.

Yet as comparative neuroanatomist Maciej Henneberg notes, we are not alone in experiencing this dramatic expansion: animals in the horse family (equids) have experienced the same tripling of brain size during this time. As Henneberg wryly observes, “There are no known indicators of the change in equid intelligence” during this period.

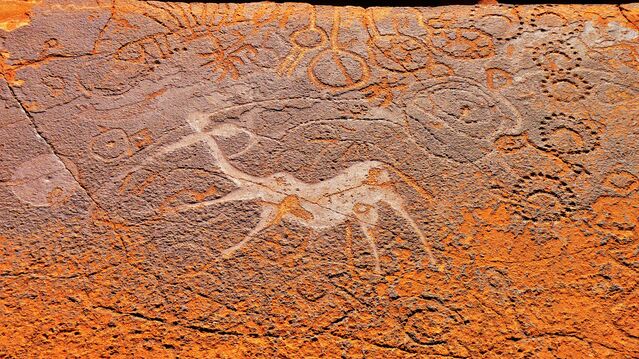

Even more strikingly, there is evidence that in our recent history, when humans have scaled the heights of cognitive innovation, our brains have actually shrunk. In the last 30,000 years, our behavior has become dramatically more complex, leading to the birth of civilization. This period saw major advances in tools, weapons, architecture, and art. As Henneberg has found, based on measurements of fossil skull size, the brain of our species appears to have decreased in size by around 10 percent over this period. Roughly, this works out to as many as five million neurons lost every generation.

It’s worth noting that fossilized remains of skulls from the paleolithic are exceedingly rare, so the available data on human brain size in the past are not extensive: they only represent estimates from a few dozen individuals. Yet there is good reason to believe these patchy data are generally correct: we know with greater confidence that human bodies were bigger in the past, and brain and body size are tightly coupled. Since our bodies (which leave more abundant fossils) are about 10 percent smaller than they were 30,000 years ago, our brains likely shrunk by a similar amount.

How could we have accomplished so much with shrinking brains? Part of the answer is that sheer size matters little, as I have argued. In fact, given that our fully human brains were already quite sophisticated 30,000 years ago, and are organized essentially the same way as they are now, we may have benefited from somewhat less brain mass. Having fewer neurons, along with less body mass, means lower energy costs. All else being equal, this means less time finding food. With lower energy costs, perhaps this also means more time and energy can be devoted to innovation and exploration. We start to see much more evidence of art, storytelling, and advanced tool-making after 30,000 years ago.

At the same time, the accretion of more material culture may represent the offloading of more and more information from our brains to objects. Innovation over the past 30,000 years didn’t necessarily require the reorganization of our brains (and there is no evidence this has occurred). Instead, we developed a more complex culture that transmitted new information from one generation to the next, all while preserving past innovations. This stored information can be transmitted faithfully for hundreds or thousands of years even in nomadic hunter-gatherer cultures.

Because of culture, no one person need keep all the knowledge in her head; it can be shared across the culture. This has been called the "cultural ratchet." Moreover, a durable object itself contains information about how it came into being. In this way, it becomes unnecessary for each person to learn and remember every innovation anew in each generation. Over time, we would no longer need as many neurons to encode memories (memory capacity does seem to be related to brain size in primates, though this doesn’t equate to intelligence). This offloading could give us the smaller and less costly but more accomplished brain we have today.

You can still argue that this is correlational evidence, which is tricky to interpret. As scientists, what we would really like to do is design a careful experiment. In the case of brain size versus intelligence, what we want to do is breed animals to have bigger brains. This has actually been done, though of course not in humans. We’ll explore this work in the next post.

Copyright © 2021 Daniel Graham. Unauthorized reproduction of any content on this page is forbidden. For reprint requests, email reprints@internetinyourhead.com.

LinkedIn image: insta_photos/Shutterstock. Facebook image: Antonio Guillem/Shutterstock

References

Culotta, E. (2010). Did modern humans get smart or just get together? https://science.sciencemag.org/content/328/5975/164.summary

Henneberg, M. (1998). Evolution of the human brain: is bigger better? Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 25(9), 745-749.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2011). Scaling of brain metabolism with a fixed energy budget per neuron: implications for neuronal activity, plasticity and evolution. PloS One, 6(3), e17514.