Anxiety

Choose to Think in New Ways

Research explores an accessible, online program to reduce anxious thinking.

Posted October 19, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Imagine that you’re at the grocery store. As you walk down an aisle, you see your neighbor placing items in their cart. You wave to them, but they keep their head down. Then, they leave the aisle without saying hello. As you continue shopping, you can’t help but think about why your neighbor ignored you. Did I do something to offend them? Are they embarrassed to say hi to me in public? What did I do wrong?

People with symptoms of anxiety often jump to negative conclusions like the ones above. These interpretations of events can be quite pervasive and are linked to feeling anxious and upset. Why is it that people think this way, and why is it more common for people with anxiety?

Cognitive biases are patterns of thinking that influence our emotional responses. For people with anxiety, negative cognitive biases can make ambiguous situations seem more dangerous or threatening. Even though the outcome of an ambiguous situation is uncertain, like the scenario above, people with anxiety tend to interpret them more negatively.

It’s important to recognize that other interpretations of why your neighbor didn’t say hi to you are entirely possible. For example, you might think: they could be running late for something or they likely just didn’t see me. Instead of assuming the negative, you simply accepted that your neighbor was busy and moved on. Flexible thinking where you consider alternate perspectives is a much healthier way of thinking that can help reduce negative feelings like anxiety.

So, how do we combat cognitive biases? How do we train ourselves to think more flexibly?

One way is to seek out therapy. Currently, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is the gold standard for treating anxiety. However, therapy is not always a viable option. It can be hard to schedule consistent appointments or may cost more than someone is able to afford. Also, it can be difficult to overcome the stigma that surrounds getting help from a therapist.

Another way to develop more flexible thinking patterns is with Cognitive Bias Modification for Interpretation (CBM-I). CBM-I is a relatively new, online form of anxiety treatment that directly targets your thinking patterns. The main goal of CBM-I is to target rigid, often negative cognitive biases and train people to think in more flexible ways. For some people, doing CBM-I may be enough on its own to reduce anxious thinking, but for others, it can be a useful supplement to therapy or may serve as a stepping stone on the path to getting help.

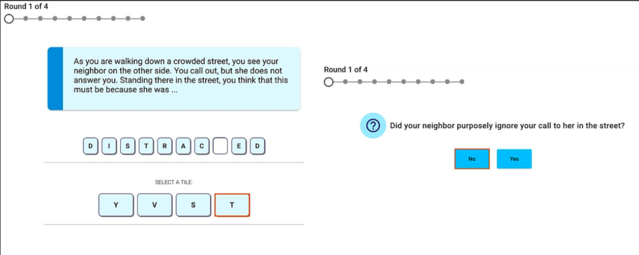

Much like CBT, CBM-I requires active participation from the individual. However, unlike most forms of CBT, CBM-I is self-guided. In a typical CBM-I session, the individual is presented with an ambiguous situation, meaning that the outcome is unclear. The individual reads about the situation and then fills in the missing letter of the last word of the situation. That last word is extremely important because it determines the outcome of the situation. After reading the situation, the individual is asked to answer a comprehension question to make sure they were paying attention.

CBM-I interventions are often structured as brief sessions that take place over the course of a few weeks. For example, our lab’s online CBM-I intervention, called MindTrails, delivers one 15- to 20-minute training session every week for five weeks. This structure allows participants to get repeated practice, which in turn gives them more opportunities to train their brains to think more flexibly.

This picture is an example of a CBM-I training session. It’s from MindTrails, an experimental CBM-I study developed by our lab at the University of Virginia. On the left, there’s an example of a training scenario, followed by a word with a missing letter. The final word - distracted - provides a resolution for the ambiguity set up in the rest of the scenario. Users select the missing letter from the available tiles so that they engage with the content and don’t just click through. On the right, there’s a question to check understanding and reinforce the meaning of the previous training scenario.

There are myriad benefits that come with CBM-I. First and foremost, it’s incredibly accessible. Many CBM-I interventions, like MindTrails, are available online. This means that it can be adapted to fit anyone’s schedule. A college student studying for a test late at night can complete a session on their computer during a study break from their dorm room, a busy parent can log on from their mobile device while they wait to pick up their kids from soccer practice. Anyone seeking help can access it anytime, anywhere, from any device that they choose. Additionally, some CBM-I interventions are free.

As noted, CBM-I is a relatively new form of anxiety treatment. That means, like everything else, it’s not perfect and research is still needed to study its effectiveness. While studies have shown that CBM-I training is effective with acrophobia1, social anxiety2,3, obsessive beliefs4, anxiety sensitivity5, contamination fears6, generalized anxiety disorder7, and depression8, results have been mixed on its effectiveness in an online setting. However, CBM-I’s effectiveness in terms of reducing negative thinking has been promising.

Now, imagine that you’re at the grocery store. As you walk down an aisle, you see your neighbor placing items in their cart. You wave to them, but they keep their head down. Then, they leave the aisle without saying hello. You think about how you’re okay with this because most likely, your neighbor just didn’t see you. So, you continue your shopping, hoping that your favorite cookies are still in stock.

Authors: Tylar Schmitt, Alexandra Werntz, & Bethany A. Teachman

References

Note: We are a group of researchers from the University of Virginia investigating the effectiveness of an online CBM-I program called MindTrails. It is designed to reduce anxious thinking and encourage people to think in more flexible ways. The program involves five 15-20 minute sessions that are spread out over approximately five weeks. If you’re interested in participating in this private, free, and flexible program, you can register at mindtrails.virginia.edu

1. Steinman, S.A. and B.A. Teachman, Reaching new heights: comparing interpretation bias modification to exposure therapy for extreme height fear. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2014. 82(3): p. 404-17

2. Brettschneider, M., et al., Internet-based interpretation bias modification for social anxiety: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 2015. 49, Part A: p. 21-29

3. Bowler, J.O., et al., A comparison of cognitive bias modification for interpretation and computerized cognitive behavior therapy: effects on anxiety, depression, attentional control, and interpretive bias. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2012. 80(6): p. 1021-33

4. Williams, A.D. and J.R. Grisham, Cognitive Bias Modification (CBM) of obsessive compulsive beliefs. BMC Psychiatry, 2013. 13(1): p. 1-9.

5. Steinman, S.A. and B.A. Teachman, Modifying interpretations among individuals high in anxiety sensitivity. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 2010. 24(1): p. 71-78

6. Beadel, J.R., F.L. Smyth, and B.A. Teachman, Change Processes During Cognitive Bias Modification for Obsessive Compulsive Beliefs. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 2014. 38(2): p. 103-119

7. Hayes, S., et al., The effects of modifying interpretation bias on worry in generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 2010. 48(3): p. 171-178

8. Blackwell, S.E. and E.A. Holmes, Modifying interpretation and imagination in clinical depression: A single case series using cognitive bias modification. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 2010. 24(3): p. 338-350