Motivation

What Keeps Us Going Creatively When the Going Gets Tough?

The motivational value of both long-term and short-term goals.

Posted November 11, 2018

Many of our important projects and goals require extended effort – effort stretched out over long periods of time, from months, to years, or even decades. What keeps us going on these projects, pursuing our long-term goals, even when, in the short-term, the road ahead seems riddled with bumps and potholes, steep hills to climb, or unanticipated setbacks?

Imagine you are embarking on an ambitious new creative project – say you want to launch your first solo artist exhibition of paintings or sculptures, or your first interactive video+sound installation, or to publish a substantial written work such as a novel, or an extended theoretical or historical analysis. Should you set highly specific and concrete attainable goals for each day, or for each week?

But we have many aspirations and hopes – should you be able to tell yourself just why this project is the one you should be taking on right now? Should you ask yourself what it means for you, or why you're taking on this big project rather than another one?

There is no single easy answer to these questions. Most of our goals do not exist on their own, in isolation from other goals, and we can think of our goals in several different ways, each of which can help us with different aspects of our thinking and motivation. Still, there are some pointers and guidance that research has uncovered.

Let's look at two common ways of thinking about our goals, and the benefits and possible drawbacks of each. We'll draw first on the insights from a team of three researchers at the University of Bern, in Switzerland, and then on findings from recent work by researchers working in Canada, at the University of Waterloo.

Goals as hierarchies, or trees

One way we can think about our goals is as trees or structured hierarchies of interconnected aims, with some goals being highly overarching or "superordinate" and others being more narrow, specific, or subordinate "stepping stones" (routes) to other goals. Superordinate goals often capture the meaning or importance of what we are doing, that is, why we seek to do what we do. They are often closely linked to our values, or our very broadest aims that span many different contexts or circumstances across our lives and steer our attention, feelings, and choices. Subordinate goals often delineate the specific methods we need to take to reach a given goal, that is, how we can achieve the desired aim.

So, if we reflect on why we want to launch a new large creative project, we may bring to mind our deep-seated beliefs about why we think creativity is an important or core value for us, such as that we believe we should try to help ourselves and others experience – and make – surprising and beneficial forms of newness in the world.

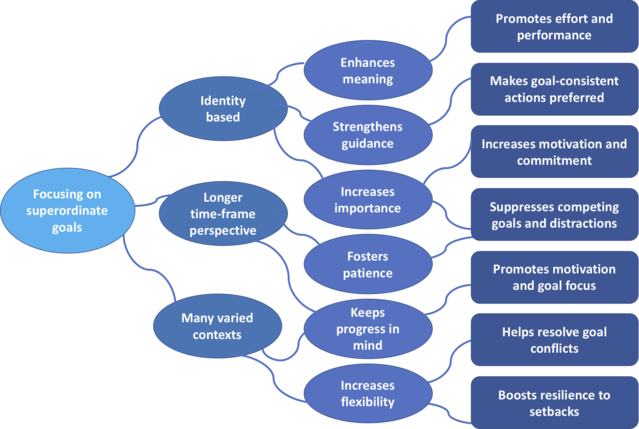

Some of the ways that bringing to mind our superordinate goals can shape and benefit our thinking and motivation are pictured below.

Thinking about our values and our sense of who we are could strengthen our sense of the meaning and the importance of what we are doing. Bringing our superordinate goals to mind could also foster a steadying sense of patience – no great creative work of art or science or culture was accomplished without forgoing some shorter-term rewards that loomed alluringly large and attractive in the moment. It also may encourage us to stay resilient and flexible because we realize that any one concrete shortcoming, any one specific setback, is only that – one among many situations and circumstances.

These may be some of the cognitive and motivational processes that lead to the often-observed beneficial buffering effects of the social-psychological intervention, called "values affirmation" or "self affirmation." In values affirmation, individuals under chronic stress or stereotype threat are asked to think about and write about their core values.

Values affirmation has been found to counteract the harmful effects of negative stereotypes on cognitive performance measures, academic outcomes, and health behaviors. Especially relevant here, values affirmation has also been found to bolster verbal insight problem solving and also to boost nonverbal insight problem solving and abstract relational reasoning. Several interrelated mechanisms have been proposed to undergird these benefits, including increased resilience, constructively orienting to errors, and regulating negative emotions while staying attuned to big-picture goals.

But does thinking about our goals as hierarchies, ranked by how important they are to us, capture everything we need? What might it leave out or lead us to overlook?

Goals as networks, or interconnected maps

The importance of a goal is not the only characteristic of our goals that we may want to consider. Exclusively taking a strictly hierarchical picture of our goals, based on their importance, may make it difficult to see other significant interrelations between them. For this reason, it may also be valuable to think of our goals as forming a network, or an interconnected map. In this network, goals that are closely related to one another would appear next to each other, and goals that are important to us would have more connections than other goals.

Take the goal of doing well as a student. Some of a student's goals will relate to the courses and coursework she has, when each assignment is due, how complex the assignments are, and how much uncertainty she has about the time and effort required to complete them. Other goals of the student will focus on her relationships with family, peers, or roommates and activities she engages in with them. In addition, the student may have goals related to leisure, volunteer work, sports activities, or other extracurriculars; and also her daily living arrangements relating to shopping, cooking, cleaning, sleeping, etc.

Thinking of your varied and various goals in this way, and placing them next-to-next in an association-based networked map, may call your attention to subtle or nonobvious interconnections that you hadn't noticed before. Indeed, researchers have suggested that this way of picturing our goals may be especially beneficial for sparking what they call "integrative" creative thinking. This form of thinking draws heavily on associative processes and may be a form of creativity that involves especially frequent and repeated shifts between divergent and convergent creative processes.

To test this goal-network idea in relation to integrative creative thinking, the researchers asked 191 undergraduate students to complete a paper-and-pencil booklet visualizing their goals for university success. The students were randomly assigned to sketch out their goals for succeeding at university in one of three ways:

(1) using a hierarchical map – with a clear ordering structure, where the higher-order goals are superior to, and encompass, the lower-order ones, and where lower-order goals may be the means to achieve higher-order goals

(2) using an interconnected network – with goals that are closely related to one another forming clusters, and goals that are more important having more connections

(3) using a series of steps – with goals organized along a timeline, such that achieving a goal at a later point in time depends on achieving goals at earlier points in time.

To test the students' "integrative" creativity, they were challenged with a creative story re-writing task. In the story re-writing task, students first read a short summary of the fairytale about Snow White, and then were asked to rewrite the story "using their wildest imagination" – developing an entirely new version of the story. Four raters, blind to the participant's condition, rated the creativity of the stories.

As they had hypothesized, the goal-network approach gave the greatest boost to creativity. The goal-network group showed the highest amount of integrative creativity on the story re-writing task. Other analyses suggested that this boost did not seem to come about because of differences in the number of goals generated for the different goal-mapping groups or other factors.

What should we make of all this? Some questions to think about...

We must not draw strong conclusions about creative processes from any one empirical study or any one theoretical perspective on the nature of goals. Still, there are reasons to think that there are benefits to both thinking of our goals in terms of our values and a hierarchy of their importance, as well as in terms of how our many goals interrelate with each other.

Putting together these recent exploratory forays into how we can and do think about our goals, seems to give rise to many new questions:

- How often are we aware of the ways in which we are picturing our goals? If we find ourselves "creatively stuck" (or otherwise stuck in our thinking) can we intentionally prompt ourselves to try adopting a different model of our goals to propel ourselves forward both cognitively and motivationally?

- What type of goal model do you most often assume when thinking about your aims and aspirations? How do your different ways of picturing your goals shape or channel your creative processes?

- How might you change the structure, or content, of how you think about your goals to more strongly foster your patience and persistence when the road ahead looks steep, or steeped in uncertainty?

- If you were asked to draw three different network maps of your goals, each showing different interrelations, or different vantage points on your goals, what goals would appear as important in each of the different networks?

- Are there any goals that are no longer "really yours" – that have become disjoined from other goals, or replaced, or merged into new aims?

- What are your "F.I.R.S.T" goals -- For the long-term, Individualized, Recurring, Superordinate, and Thematic?

References

Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371.

Creswell, J. D., Dutcher, J. M., Klein, W. M. P., Harris, P. R., & Levine, J. M. (2013). Self-affirmation improves problem-solving under stress. PLoS ONE, 8, Article e62593, 1–7.

Höchli, B., Brügger, A., & Messner, C. (2018). How focusing on superordinate goals motivates broad, long-term goal pursuit: A theoretical perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1879, 1–14.

Kung, F. Y. H., & Scholer, A. A. (2018). A network model of goals boosts convergent creativity performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1910, 1–12.

Wen, M-C., Butler, L. T., & Koutstaal, W. (2013). Improving insight and non-insight problem solving with brief interventions. British Journal of Psychology, 104, 97–118.