Dunning-Kruger Effect

Dunning-Kruger Isn't Real

The least knowledgeable people are not the most overconfident.

Posted December 30, 2020 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

The Dunning-Kruger effect is commonly invoked in online arguments to discredit other people’s ideas. The effect states that people who know the least about a topic are the most overconfident about that topic while people who know the most tend to be more humble and accurate in their self-assessment. It seems intuitively right, and it’s often a way to undercut people who present their opinions and arguments with "absolute certainty" that they’re right. The only problem is that the Dunning-Kruger effect itself is wrong.

Discussion about the Dunning-Kruger effect recently surfaced online in response to a blog post in which a blogger contacted a statistically savvy psychologist at George Mason University, Patrick McKnight, to work through recent criticism of the effect. The way they approached the problem reveals a lot about how to check what we think we know about psychology research. (I've since found that this ground was previously covered in a 2010 blog post, and most of the deep insights come from a 2006 paper.)

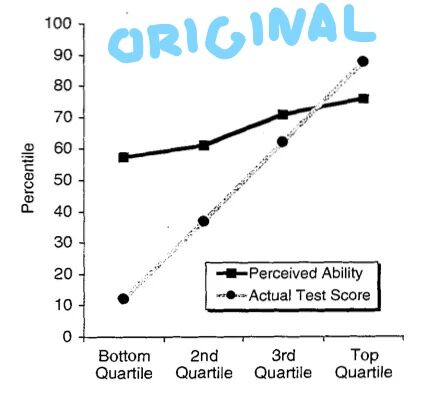

First, let’s consider how we came to believe in the Dunning-Kruger effect. Classic studies on the topic ask people to judge how well they would perform on various tests of intelligence and social skills, and then compares their actual performance on those tests to their peers. It turns out that people who did the worst estimate their performance to be much higher, relative to their performance, than others. In fact, this over-estimate of how well they did gets smaller and smaller the better the person actually did. This suggested to psychologists Dunning and Kruger that people who don’t know much are more overconfident than those who know a lot.

This seems like a reasonable interpretation of the data. However, a next step often taken in other sciences—but seldom taken in many areas of psychology research—is to try to create a specific, mathematical description of the process underlying the effect. This is a model. Models allow us to create a simplified universe where we know exactly how all the pieces fit together—because we’ve written out what we think is happening. The goal is to then see how well this description of the process fits the real data we collected. If the fake data we got from the model looks like the real data we see when we actually measure people, we can have some confidence that the model is right.

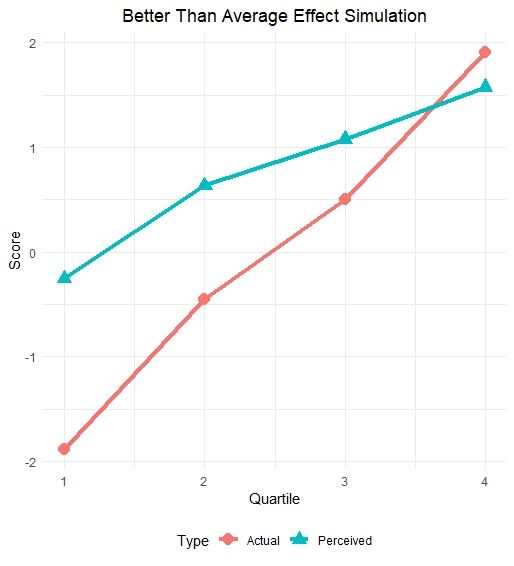

The controversy stirred up around Dunning-Kruger by the recent blog post was based on McKnight finding that he could create something that looked a lot like the Dunning-Kruger effect from a model where the worst performing people weren’t any more or less wrong about their skill level. People were just wrong randomly, and the pattern looked similar to the one originally published by Dunning and Kruger. A refinement of this was then posted by Benjamin Vincent of the University of Dundee in Scotland. In Vincent’s version, people were biased, but there was no difference between those who know the most and those who know the least. Everyone was just a bit overconfident in their abilities, no matter what level they were at. This matched the observed data beautifully.* (I reproduced the figure below, adjusting the data slightly to suggest that it's harder to measure people's real skill than their personal judgments. Code is publicly available here.)

In a paper out this year, Gilles Gignac and Marcin Zajenkowski follow arguments that the Dunning-Kruger effect can be better explained by the combination of two factors:

- The “better than average” effect (the universal positive bias Vincent explored).

- Regression toward the mean (a statistical pattern common when two variables aren’t perfectly related).

Further, they argue that if the Dunning-Kruger effect is actually about people with little knowledge in an area not knowing how little they know, then we would expect other statistical patterns that aren’t seen in real data. Instead, they use a sample of 929 people’s scores on IQ tests to show that the results look like classic Dunning-Kruger—but are actually better explained by everyone being overconfident and there being normal statistical error.

This debate highlights a point central to recent discussions of how best to reform psychology. On the one hand, reformers (like me) suggest that we need to make sure that the effects we publish can replicate. Otherwise, we risk drawing conclusions about patterns of data that might have just been a fluke. On the other hand, reformers from the mathematical psychology and modeling community suggest that we need to start by considering how the processes might work—starting with the model—before deciding what results we would expect to see. They would argue that even a result that replicates consistently, like Dunning-Kruger, might not properly explain what’s going on if we don’t stop to think about the process that leads to the result. The Dunning-Kruger debate of December 2020 illustrates very clearly why psychology reform needs to do more than just make sure research replicates.

So now if someone online says something cutting about how the person they're arguing with is too stupid to know they’re wrong, you can point them to this post. There is no Dunning-Kruger. Everyone thinks they’re better than average. How’s that for taking the wind out of a dunk?

* Incidentally, Vincent argues that this shows that there is a Dunning-Kruger effect, because people are biased, but that’s it’s just a different effect from the one in the literature. Knowing more doesn’t make people less biased: Everyone’s equally biased. I’m saying this means we have a different effect, but the argument is just about whether we shift the meaning of Dunning-Kruger or use a different label.

References

Kruger J, & Dunning D (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77 (6), 1121-34 PMID: 10626367

Burson KA, Larrick RP, & Klayman J (2006). Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: how perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (1), 60-77 PMID: 16448310

Gignac, G. E., & Zajenkowski, M. (2020). The Dunning-Kruger effect is (mostly) a statistical artefact: Valid approaches to testing the hypothesis with individual differences data. Intelligence, 80, 101449.