Coronavirus Disease 2019

5 More Ways That COVID-19 is Not Like the Flu

The molecular details help explain why SARS-COV-2 is so dangerous.

Posted May 8, 2020 Reviewed by Devon Frye

This post continues from my previous article, which discusses the clinical differences between COVID-19 and the seasonal flu. These two diseases progress so differently because the viruses that cause them, SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza, respectively, have very little in common. Here I discuss the fine molecular details of these two viruses and how they attack us.

1. The Virus Particles

Viral particles come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, and compositions. While this may sound like an esoteric detail, the composition of viral particles is what determines how a virus finds and enters its preferred host cell. Viruses are called obligate intracellular parasites, because they cannot do almost anything on their own. They must enter a host cell and hijack it. They then reprogram that host cell to become a factory for making more viruses, eventually spilling them out to attack more cells.

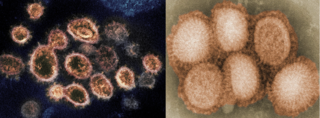

Both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 particles consist of a lipid envelope, which is an outer covering made of fat molecules taken from the previously infected host cell, the one that produced the virus. This is why handwashing is a key defense against both viruses—soap dissolves the fatty envelope and destroys the viral particles.

Embedded in the lipid envelopes are so-called "spike proteins." For influenza, this spike protein is called hemagglutinin (HA), while the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is called glycoprotein S (gS). HA and gS are totally unrelated and unlike each other. Because the spike proteins are what find and stick to the host cells, this explains why influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infect totally different cells.

2. Host Cells

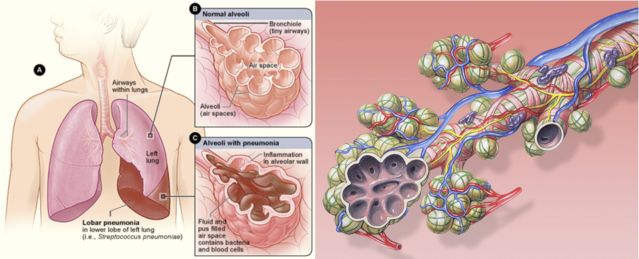

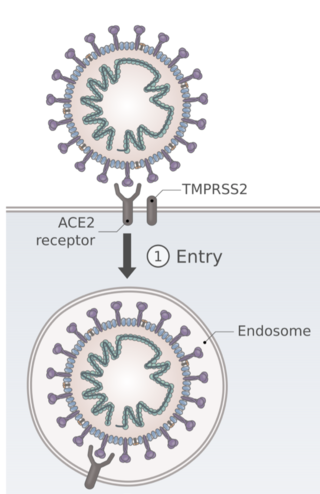

The HA spike protein of influenza sticks to sialic acid, which pokes out from the surface of the cells that line the throat, nasal passages, and larger airways of the lungs. Those are the target cells of influenza, which helps explain why this infection results in heavy mucus production. The gS spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, on the other hand, sticks to the ACE2 protein which is found on cells very deep in the lungs. Totally different spike proteins means totally different target cells.

In fact, the main target cells of SARS-CoV2 are the alveolar cells, which form the very end of the airways, the microscopic sacs of air surrounded by blood vessels where gas exchange takes place. In other words, SARS-CoV-2 viruses infect the exact cells where oxygen is absorbed by the lungs. This is why severe cases of COVID involve dangerously low blood oxygen levels. No matter how much air they inhale, these patients cannot absorb enough oxygen because the cells in which this happens are ravaged by the infection. Normal air only contains about 20 percent oxygen, so giving patients 50 percent or even 100 percent oxygen usually helps.

(UPDATE: A new study found that ACE2 receptors are also found in the nasal passages and, while this is not the main cause of morbidity and mortality, it is likely the route of first entry for the virus, helping explain why this bug is so contagious.)

3. Receptor Proteins

As mentioned above, influenza viruses bind to sialic acid, which is found on the inner surfaces of the large spaces throughout the respiratory system. Influenza binds there, enters the cells, and begins the infection. The receptor protein that SARS-CoV-2 binds to, however, is called ACE2 and this is a much more interesting story. In fact, COVID-19's path to infection through ACE2 might explain a few of the peculiar things about this illness.

ACE2 stands for angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and, as the name implies, it is a critical protein for maintaining our blood volume and our blood pressure. It is located in the tiniest air sacs in our lungs because this is where it can make extensive contact with the bloodstream through the millions of tiny vessels that surround these air sacs. We know that individuals with high blood pressure and other cardiovascular diseases are at increased risk of developing and dying from COVID-19 and the ACE2 receptor may be partially to blame.

In addition, there is data that patients on ACE2-inhibitors (a blood pressure medication) have better outcomes than those with high blood pressure that are not on ACE2-inhibitors, not only further implicating this receptor in the severity of COVID-19 disease, but also opening up a potential avenue for treatment. ACE2-inhibitors are among the many drugs being tested as COVID-19 treatments.

ACE2 might also explain two of the demographic patterns of COVID-19. This disease seems to infect children only very rarely, unlike influenza, which sickens children mercilessly. This is believed to be because the lung cells of children have much less ACE2 on them than adults' do. The SARS-CoV-2 virus simply doesn't stick to children's cells.

Further, men are at greater risk than woman, by a factor of two, of both contracting and dying from COVID-19. Once again, the expression of ACE2 may explain this, as it is known to be expressed more in men. Hypertension is also more common in men than in women. ACE2 may be the key factor connecting all these variables.

4. Genetic Material

SARS-CoV-2 is in the Coronavirus family and the viruses that cause the seasonal flu are Influenza viruses. While both use RNA instead of DNA for their genetic material, SARS-CoV-2 has a single piece of +RNA (or "sense RNA") which looks very much like our own natural mRNA and can be read by our cells as such. This genome encodes 14 proteins and is very large by viral standards.

The genome of influenza viruses, on the other hand, consists of several small pieces of RNA, which is itself very unusual among viruses. Their tiny genome encodes just 8 proteins, but, even more strangely, it is made of "-RNA" (or "anti-sense RNA"), which cannot be read by the cell in its original form.

While this may seem like an arcane difference, it shows that the two viruses are only very distantly related. They are in the same phylum (the way that humans and great white sharks are), but their ancestors diverged tens or hundreds of millions of years ago. Also, the different kinds of genomes means they hijack our cells in different ways.

5. SARS-CoV-2 is a "Novel" Coronavirus

With occasional exceptions, the strains of influenza that circulate globally each year, causing the seasonal flu that sickens millions, are variations of earlier strains that have also circulated. They are not wholly new to us, just mutated a little bit. This means that the antibodies we have from getting the flu (or a vaccine) in previous years are often partially effective in future years. They won't completely inhibit the new strain, but they will weakly stick to it, like a weight dragging it down, and this reduces the severity of the infection, slowing its progress while our immune system scrambles to generate specific antibodies. This translates into a shorter, less severe illness.

SARS-CoV-2 recently jumped from bats to humans, making it a "novel" virus. It is not merely a variation of something our body has seen before. (Despite the similar name, it is NOT a mutant of SARS-CoV-1, which caused the SARS outbreak of 2002.) As far as our immune system is concerned, SARS-CoV-2 is entirely new and none of the antibodies in our arsenal recognize it.

Therefore, the infection has a big head start, unfettered by any antibodies. By the time we begin to make antibodies to fight it, it has already established itself throughout our lungs (and other tissues, it seems). Once an infection is entrenched in our own cells, it is much harder to clear because we can't simply kill all the virus-producing alveolar cells because then our lungs won't work at all. In fact, that is part of why COVID-19 is so deadly. Both the virus itself and our immune system team up to attack the very cells that perform a critical role in our bodies—getting oxygen from the air.

The flu is occasionally caused by novel viruses as well, recently jumped from some other species. You've probably heard of swine flu, bird flu, and so on. That's precisely why these were deadly pandemics and not just the regular seasonal flu. They weren't just slight tweaks of viruses that we've been building antibodies for over the course of our lives. (Side note—if you get the flu vaccine every year, you likely build up cumulative immunity that can protect you in future years.)

***

It is tempting to want to minimize the terrifying threat that COVID-19 poses, but COVID-19 and the flu are very different illnesses because they are caused by very different viruses. The continued comparisons are not just unhelpful, they are part of wild conspiracy theories and a massive misinformation campaign that public health officials are now calling the infodemic.

Please be part of the solution, rather than the problem, by sharing articles based on real science without political agenda. And please stay home as much as possible. When you must go out, wear a mask, keep your distance from others, and wash your hands thoroughly before and after. By slowing the spread of this disease, we can give our scientists and healthcare providers the time they need to develop treatments that are urgently needed for the most vulnerable among us.