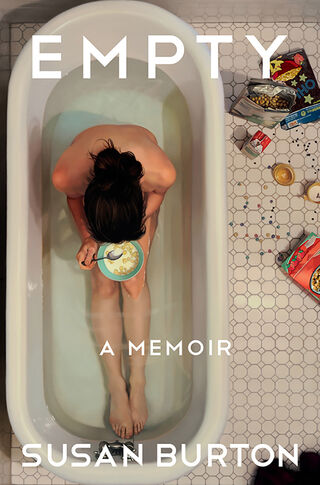

Satisfied: Learning to Confront Anorexia and Binge-Eating Disorder

Coming to terms with disordered eating in adulthood.

By Susan Burton published June 19, 2020 - last reviewed on July 14, 2020

2000

Days in Chicago began with muffins. Blueberry muffins, four to a plastic pack, from a Whole Foods with massive aisles, the scale of this grocery store as novel to me as the sprawling prairie city itself. I’d spent my early twenties in Manhattan, cramped and exhilarated. I’d moved to Chicago for a dream job, but I felt homesick and dislocated.

I was 26 and a producer of a public-radio show. For years I’d listened to this show and had imagined working there—and then a job had opened up. On the night I’d stood at a FedEx counter, sealing the envelope with my application, my boyfriend had said, “If you send this, you’re going to get that job.” Getting the job would require me to leave New York, and him. It felt like an impossible decision, and as soon as I had to make it, I started binge-eating again.

Since my mid-teens, I’d cycled between anorexia and binge-eating. During college the bingeing had taken over my life. I’d dropped classes, burrowed under the covers of my top bunk, closed my eyes. But I was too ashamed to tell anyone about what I did. When I finally managed to stop, I resolved to never speak of it. It’s no surprise to me now that what I never examined came roaring back; also no surprise that it returned when I had a difficult choice to make. I had always used bingeing to get away, avoid, dissociate. But as a young woman, I didn’t see any of this. I just hated myself for losing control.

One night in April I came home from work, the softball-size muffins I’d consumed in the morning having finally “dissolved,” which was how I thought of it. I had a headache, as I did most days. The obliterating flood of sugar would recede by mid-morning, and a dull pain would follow. I hated myself; I couldn’t think, except to beat out the mantra, must not eat, must not eat. On the patio at lunchtime, a coworker had opened the lid of a homemade chickpea salad, and I’d watched her longingly, jealously. I wanted what she had. Which was not so much the food itself, but what it represented, something regular, even-keeled. There was nothing “even” in my days, in the spike and crash and quiet fury, in the exhaustion, isolation, and stoniness.

I was going to eat perfectly tonight and tomorrow, start fresh. On the stove, I boiled water for couscous and heated frozen peas. The range, a dated one, bore the name of a manufacturer called Caloric. This was the dark humor of my rental: an appliance named for the metric that defined my life.

This bland meal was not satisfying. But the only way I knew to satisfy myself was by doing what would come next; of course it would, I knew it would. Who was I kidding? As soon as I had put the bowl in the sink, I was crossing the kitchen and opening the built-in hutch that after six months I still thought of as belonging to the previous renters; it held their smells, their dust. I was a transient, nothing here was mine. Except for the food. That was mine. And bingeing. That was mine, too. That force of feeling—desperation, ferocity, release—was known to me entirely.

I tore open a bag of pretzels, dug in a hand. These pretzels, shaped like chain links on a necklace, dense and honeyed, dried my mouth. But I never drank during a binge. I addressed any problem with food alone. Thirst I would sate with frozen yogurt. I went to the freezer, which did feel like mine. The landlord had replaced it before I moved in, as if he intuited what I needed most, an insulated case for my most precious treasures.

I kept going and by the end I was scared, my heart fast, my body thick. I walked across my apartment, stripping off my clothes as I went—bland clothes from a chain store, clothes that I didn’t think were “me.” So many of my questions were about who I was and what was mine, but I couldn’t engage them because I couldn’t reach them. They were buried beneath all the food, everything I’d eaten compacted on top of them.

2012

On an August morning, living in Manhattan once again, I settled into a stuffy room in the library. I’d chosen this room precisely because it was not air-conditioned. At 38, I was always cold—anorexic again, though I didn’t perceive this as a term that applied to me. I didn’t think I was thin enough to be anorexic.

I hadn’t binged for years. Eating had shifted into not eating: an equation of undoing. What I didn’t see, or refused to, was that this was an equivalency. Eating was the same as not eating. Both used food to manage feeling.

There was so much I still didn’t understand about my eating disorders, but this was a morning on which I began to crack the lid.

I opened the cover of my laptop. I was doing research in a science database when I thought: I bet there’s stuff about binge-eating in here. What preceded this thought, I’m not sure, but once the idea arose, the urge to type the phrase into the search box was insistent. I pressed Return, and my heart sped; this felt taboo. I’d still never told anyone about my bingeing.

I’d always found identification in novels and memoirs, but that morning I found it in academic papers that described not only my symptoms, but the feeling state that had accompanied them. A paper, published in Psychological Bulletin in 1991, captured my experience of bingeing exactly, as a “short-term escape from an aversive awareness of self.” Yes, this is how it felt to be “narrowing attention to the immediate stimulus environment and avoiding broadly meaningful thought.”

I was buoyant with recognition. But my appreciation was almost literary, focused on the precision of the description. I didn’t take the next step. I didn’t ask the questions the paper might have prompted me to. What am I shutting out? What don’t I want to face?

2019

On the subway home from therapy, I felt as raw as I had during the session.

At 45, I was finally working toward recovery from my eating disorders. In the course of writing a memoir of my adolescence, I’d come to recognize how profoundly my life had been limited by my problems with food, and that solving these problems was not just a matter of setting them down on paper in private but of understanding them with another. While I’d tried therapy more than once in my adulthood, I’d never gotten past the initial consultation. The difference now was that I was ready to open up and that I had found someone I wanted to open up to, a psychoanalyst who specialized in eating disorders and addictions. With her, I was exploring why I’d used food the way I had and facing up to how I used it still.

At home in my kitchen, I opened the refrigerator. It was lunchtime. I wanted yogurt with a little granola. This was contained, predictable. But I knew it would leave me wanting more. In the past this would have been precisely why I’d chosen it, for the empty feeling that would follow. Now I was trying to learn how to feel satisfied.

There were leftovers: roast chicken, kale, and cauliflower with slivered almonds and currants. I sat down and opened the newspaper. Reading while I ate was an enduring habit, part of the detachment that had once been central to a binge. While I’d never returned to bingeing, food was still something I went into a tunnel to consume. I still used it to dissociate.

When I finished, I went back to the counter and put more on my plate. Was I hungry? I wasn’t sure. But I knew that once I stopped eating I would have to return to the world. I would have to face whatever I didn’t want to face, decide whatever I didn’t want to decide, do the next thing. I ate more so that I didn’t have to go back yet.

I felt the small panic I always felt when faced with an empty plate.

So many of my behaviors and thought loops were so entrenched. Once I would have pushed the thoughts away and determined to be “better.” But now I was curious about them. What exactly was I so scared of this afternoon? What choice didn’t I want to make?

There were a lot of reasons I’d struggled with food. It wasn’t going to be simple to untangle them, and it wasn’t going to be easy to change. But I had started to ask the questions, even if I didn’t know the answers yet.

I broadened my attention and left the “immediate stimulus environment.”

I stood up from the table and returned to the world.

Susan Burton is the author of Empty: A Memoir. She is an editor of This American Life.

LinkedIn Image Credit: Creativa Images/Shutterstock