Education

Hiding in Plain Sight

Historical research about intellectual disability.

Posted February 2, 2017

Guest Blog written by Diana (Dee) Kantovich, Assistant Director, Peer2Peer Coordinator, Taishoff Center for Inclusive Higher Education, School of Education, Syracuse University

“If you believe that people have no history worth mentioning, it’s easy to believe they have no humanity worth defending.” --William Loren Katz

Everything you thought you knew about the history of people with disabilities in the United States is wrong.

It’s understandable; disability is not a topic covered in your standard American History curriculum. While there are occasional mentions of disabled individuals—Helen Keller comes to mind—the lives and experiences of disabled people are largely ignored. And that’s a shame; it is a fascinating topic that has volumes to teach us about how American culture views differences, defines stigma, and responds to change.

Fortunately, there are places like the Museum of disABILITY History in Buffalo, New York that can introduce the public to this history. The museum is a project of People Inc. and focuses specifically on the history of people with intellectual disabilities, a history that is particularly hard to find. Of all disability categories, intellectual disability is the most stigmatized and the least often studied through a historical lens. Throughout the history of the United States, people with this label often lived invisible lives. Approximately 10% of people diagnosed with intellectual disabilities vanished into the special hell of large state institutions. Other people lived in their home communities, under the care of their families or the state; however, their freedom to work, to live independently, to marry, and to make families of their own were curtailed by policies, attitudes, and other forces beyond their control. Families, aware of the stigma, sometimes actively avoided drawing attention to their disabled loved ones. While other groups of disabled people could write their own histories and memoirs, people with intellectual disabilities often had both limited literacy and opportunity to tell their own stories.

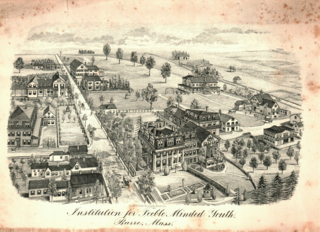

Even the earliest form of community involvement—public education—was not guaranteed to students identified with intellectual disabilities until 1975, when the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA) was passed. However, before the 1970’s some classes did exist in the public schools, and there were private schools for children with disabilities. The first experiments in teaching intellectually disabled children began much earlier, in 1848. It was at the Museum of disABILITY History that I saw an early photograph of this school. The caption under it identified the school as an “Institution for Idiots” in Barre, Massachusetts founded by Dr. Hervey B. Wilbur. I was intrigued. It took several years of work, but in September of 2016, I published my book Beautiful Children: The Story of the Elm Hill School and Home for Feebleminded Children and Youth.

While searching for a focus for his medical work, Dr. Wilbur discovered the work of a French doctor named Edward Seguin. Seguin had begun trying educational techniques to teach children diagnosed as “idiots” who were confined to the Bicetre Insane Asylum, and he had met with unexpected success. He began writing about what he called the “physiological method of treatment” for intellectual disability, resulting in his book titled, Traitement Moral, Hygiène et éducation des idiots et des autres enfants arriérés, published in 1846.

The method emphasized the direct teaching of the body and the senses to engage with, understand, and control the environment in which the disabled child lived. It was not so different from the teaching and learning of typical children, but disabled children needed more time and more intense teaching and practice to master these skills. Dr. Wilbur, thrilled by this new information, took a few boys with cognitive delays into his home to teach them using this method. By 1851, his work had gained such renown that he was selected to become the Superintendent of the New York State Asylum for Idiots, the second publicly funded state school for the intellectually disabled (Massachusetts had the first). He recruited Dr. George Brown to take over the small school in Barre, Massachusetts, which came to be named the Elm Hill School and Home for Feebleminded Children and Youth. Dr. Brown’s family maintained the directorship of this private school for the next ninety-five years, until it finally closed in 1946.

With what we know now about the horrific conditions in large state institutions, and the disadvantages of segregating students with intellectual disability, it’s hard to wrap the mind around the place called Elm Hill. However, for its time, the school was revolutionary, and not just for its use of the physiological method. State schools around the country adopted the physiological method; in order to keep their funding, however, the schools only accepted children who had the best chance of becoming independent and productive enough to return to their communities. Elm Hill, being privately funded by well-to-do parents had no such mandate. They could take the children who could not walk, talk, or feed themselves, and could return them to their families in better health and easier to care for, as well as children who could learn to read, write, and work independently.

As the number of students grew, the school grew, too. The school was situated on several acres of lush farmland. As part of their “treatment” the students were taken outside as much as possible. Many students had their own horses and carriages. They spent their days doing exercises in the gym, learning basic academics in the classroom, performing chores to learn how to follow a routine, and attending evening entertainments that befitted their social station, under the watchful eye of the teachers, matrons, and directors. The students lived in private and semi-private rooms, with boys and girls separated into different buildings.

In 1876, Dr. Brown joined a group of other directors who operated schools for the “feebleminded”, and together they created the Association of Medical Officers of American Institutions for Idiotic and Feebleminded Persons (the association still exists as the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities or AAIDD) to study the causes of intellectual disability and to share best practices for teaching. Catharine Brown, Dr. Brown’s wife, was elected to the association in her own right, and shared several papers over the years of her membership. She was a driving force behind the success of the Elm Hill School.

The golden years of Elm Hill and other schools lasted for about thirty years. Then, the great pioneers—Edward Seguin, Samuel Gridley Howe, Hervey B. Wilbur, and George Brown- died, and were replaced by men who had different views about people with disabilities and their place in society. There was great hope in the early years that children with intellectual disabilities could be “cured” or at least given the skills for complete independence in adulthood. When it became clear that intellectual disability was a lifelong attribute that might always require some support, the new directors questioned the need for such intensive teaching. The pseudo-science of eugenics became widespread and promoted the idea that people with intellectual disabilities (among many others) were “unfit” to marry and have children, and recommended strict segregation so that they would not become an undue “burden” on society. Tens of thousands of people were forcibly and unknowingly sterilized, some as a condition of release from institutions.

Elm Hill carried on into the 20th century by adapting to the times. They began to accept disabled adults as permanent residents, and the number of school aged residents dwindled. The school’s buildings and land began to be sold off for other purposes. Finally, Dr. George Percy Brown, the grandson of Dr. George Brown, decided to close the school permanently in 1946, and the remaining residents—all older adults—were transferred to other facilities.

Precious documents about the history of Elm Hill are stored in the archives of the College of Physicians Medical School Library in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the collections of the Barre Historical Society in Barre, Massachusetts. Far too often, people with intellectual disabilities have been relegated to a footnote in American history; the ongoing trauma of the eugenics era often meant that families were terribly ashamed of their disabled members and kept them away from a world that had labeled them a menace. To find a large collection with information about disabled people who were individuals with families, abilities, and interests is rare and enormously valuable. The College of Physicians collection even contains several journals kept by students about their daily activities, as well as extensive records of their medical and family histories.

The information is so complete that I could trace the stories of several students from admission until they left the school when it closed in 1946.

Most precious of all are the photographs. The Elm Hill School had an exhibition in the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, so the school and its buildings were extensively photographed for the display. Samples of student work for the exhibition are also preserved.

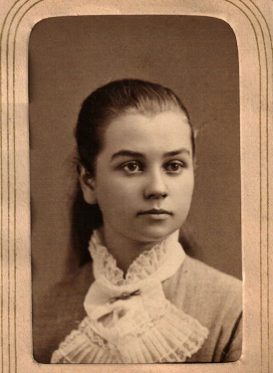

Two photograph albums stand out: one holds formal pictures of the staff and the other, formal photographs of the students. At a time when there was so much shame surrounding disability, these portraits are remarkable. The pictures were clearly taken to show the residents in their best light—they are wearing formal clothing, their hair is styled, and they are posed against elegant backgrounds. These children were loved and valued by their families and their caretakers. They were real people, with interests, ideas, and stories of their own.

All of this information points towards a much more nuanced history about the lives of people with intellectual disability than we previously understood. Certainly, some people were hidden away by their families or sentenced to live in horrible institutions. But there were many, many individuals who lived their lives without fanfare. Where are their stories? How can we use the lessons of history if the history itself is incomplete?

Practically everyone I speak to who is fifty or older can remember a family member, a family friend, neighbor, or someone else they knew growing up who had some type of intellectual disability. I feel an urgency about gathering these stories before they are lost for good. It nearly happened in my own family; my grandmother had two sisters who had significant physical and cognitive disabilities. After her death, and the death of my mother, aunt, and uncles, there was almost no one to remember that my aunts even existed.

Do you know an individual with an intellectual disability who was born in 1965 or before? Were their people with cognitive disabilities further back in your family? If so, please record the story before it’s too late. If you feel so moved, please share them with me at historyworthmentioning@gmail.com or on my Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/HistoryWorthMentioning