Proxemics

The Erotic Return of Footsie

Navigating "personal space bubbles" in the era of social distance dating.

Posted June 30, 2020

As anyone who has ventured into the realm of social distance dating knows, even slight trespasses of the 6-foot barrier now feel suddenly salacious.

When your 6-foot-distanced hiking date moves in (5.5 feet?!) to show you a picture on their phone, it feels like the quarantine-time equivalent of sneaking an arm around a shoulder, or, I don’t know ... a promise ring? Leaning into a date’s 6-foot bubble can be interpreted either as promiscuous behavior or a desire for commitment—leaving some of us wishing the quarantine overlord would materialize for a good old-fashioned “What are your intentions towards my daughter?” conversation.

Personal space is like an invisible bubble that we wear around ourselves wherever we go. When pigeons perch on telephone lines, they tend to space themselves evenly apart, and people do the same thing. While we now find people waiting in line at grocery stores and IKEA parking lots at 6-foot intervals, the tendency to space ourselves evenly was already there—just at shorter distances. We’ve always had personal space bubbles—which I find amusing to imagine as big pink soap bubbles we bounce around in—but now our bubbles have expanded. (To clarify, “bubble” refers here to personal space norms, not to the recent practice of forming “support bubbles” or “social bubbles” to socialize with additional households.)

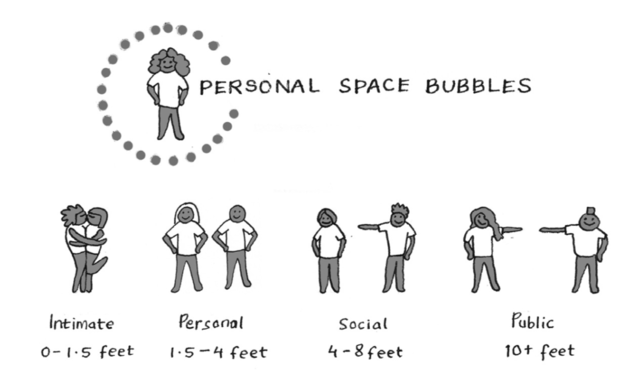

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall was one of the first researchers to establish “proxemics” — personal space dimensions — through a series of observational studies conducted in the 1960s. Hall discovered that people have four key sizes of personal space bubbles, which we inflate and deflate depending on where we are and who we’re with. But Hall believed there was more to read into proxemics than calculations of population density. He saw the space between people as a form of communication.

Working in the US State Department to train foreign service personnel for posts in disparate parts of the world, he encountered intercultural communication issues from Japan to Syria to Germany. He found that “the way in which both time and space were handled constituted a form of communication.” This “silent language,” he believed, functions like part of the DNA of the cultures it is rooted in.

The dimensions of our personal space bubbles have always varied culturally (and sub-culturally, even within the US), but also according to the closeness of our relationships. Hall found that the most intimate level (0 to 1.5 feet) was reserved for romantic partners, comforting gestures, and special scenarios like sports and theatre seating. At the personal level (1.5 to 4 feet) we interact with close friends and pass by people in a shop or the office kitchen when necessary. For more formal and impersonal dynamics, we wear our social distance bubble (4 to 8 feet). And for public settings — performing or speaking to an audience — we prefer a distance of more than 10 feet.

After many months of practicing social distancing, we’ve developed a whole new set of personal space bubble norms. Looking at Hall’s diagram, one might say we’ve moved each type of social interaction into the next level of space bubble, like hermit crabs moving into bigger shells.

Personal connections (close friends and family we don’t live with) have been bumped up to the social distance range of 6 feet. You may notice that it feels especially awkward to maintain the proper distance from your closest pals. The “social distance” bubble communicates the more distant type of interaction you would have had with a casual acquaintance in the past. And then there’s a new iteration of close talkers. The neighbor who comes right up to the 6-foot line for a casual chat when you wish they would respect your 10-foot public interaction bubble!

Navigating in this new “silent language” is perhaps most confusing for dating, where progression from the social to intimate space bubbles usually plays a key part in communicating interest and developing closeness. Is your hot Saturday night social-distanced date sitting a whole 12 feet away because he’s playing it safe? Or is that extra 6 feet saying that he’s just not that into you?

It is often said that 90 percent of communication is non-verbal, and one of Hall’s most interesting theories was that our bubble boundaries are defined by the distances within which human perceptual organs operate. Inside our intimate bubble, touch tends to trump verbal communication. Scent, temperature, and even taste are potentially palpable.

In the pre-pandemic personal bubble, you were within reach: standing elbow-to-elbow or one arm’s length away. Verbalization begins to account for a larger share of communication at this distance. But critically, touch was still possible in the personal bubble, whereas the social bubble placed you just out of reach. Moving towards the public bubble distance, we’re completely out of range for sensory inputs like smell (hopefully) and start to rely on more exaggerated movements and speaking volumes to communicate. I tested this theory out a few times—pre-quarantine—and was surprised to find how accurate it was. Whether sitting or standing, I found myself reliably just out of reach from informal “social” acquaintances I was in conversation with, while closer “personal” friends would be within reach.

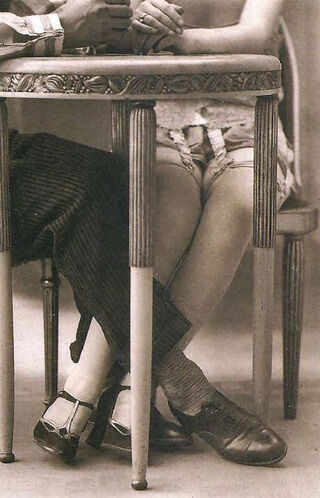

And this brings us to why playing footsie has taken on the proportions of intimate canoodling one imagines it might have held for our great-grandparents. Finding ways to feel like you’re still “within reach” of a date—while maintaining that critical 6 feet—can go a long way towards communicating on a tactile, personal level. Bodies come in all shapes and sizes, but most adults should be able to reach their toes out to touch while keeping their faces 6 feet apart.

But please, practice safe footsie! Find yourself some grass or sand to lounge on and stretch your legs out. Next time you get an awkward “someone else I took a 6-foot walk with tested positive so you might want to get tested too” phone call, you’ll be happy you kept your date safely outside your 6-foot bubble.

Sections of this piece are adapted from The Shaping of Us: How Everyday Spaces Structure Our Lives, Behavior and Well-Being (Trinity University Press, 2019).

Please note: While some of Hall's assumptions in cross-cultural comparison have not held up to the test of time, his findings on personal space as a form of communication have persisted as an important psychological principle.

References

Hall, E. T. (1968). Proxemics [and comments and replies]. Current Anthropology, 9(2/3 April-June), 83-10, 84.

Bell, P.A., Greene, T.C., Fisher, J.D., & Baum, A.S. (2001). Environmental Psychology, 5th Ed. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College Publishers.

Hall, E.T. (1959). The Silent Language. New York: Doubleday.

Hall, E.T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. New York: Doubleday.