Pareidolia

When Is a Face Not a Face?

Our minds are wired to recognize patterns, but does that set us up for mistakes?

Updated November 3, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

I recently wrote about the geode that went viral because of its resemblance to Cookie Monster. In that article, I called pareidolia, the human quirk of finding patterns in random sets of data, “a mistake of the mind.”

Face pareidolia, what we experience when we look at the Cookie Monster geode, occurs so quickly we don’t have time to analyze what’s happening. The whole process takes place outside our conscious awareness and in just 170 milliseconds.

Our brain's large facial recognition areas latch on to the common characteristics of a face—two dots over a line are usually enough—and fire off a “face!” signal. By the time we become aware of what we’re looking at, we’re already seeing a face, making it very difficult to “un-see” these illusions.

There’s a philosophical question, though, behind the physiology of pareidolia: Is it really a mistake?

When is a face just a face?

In an article for The Atlantic, Rebecca J. Rosen wrote that “things around us do sometimes actually have the shapes that constitute a face. How can we say this is pareidolia, a strange phenomenon that is supposedly the byproduct of millions of years of evolution, and not just the basic truth that sometimes shapes do look like things they are not? ‘

Rosen suggests that we should take these perceptions at face value if you’ll pardon the pun. She locates pareidolia in the world out there, in the physical similarities between objects.

“Faces are, after all, just a series of well-arranged polygons,” she writes. “Sometimes, inevitably, shapes will be arranged in the formation of two eyes, a nose, and a mouth.”

Always illusions

I take a different perspective. I locate pareidolia in the world here, in the way our bodies and our brains translate input to sensation to perception.

I’d say that whenever we misidentify an object as something it isn’t, no matter how close the resemblance, we’ve been fooled by our senses and by the very specific ways our sensory systems have developed to interpret the world around us. These types of perceptual errors happen because we unconsciously prioritize certain aspects of what we see over others.

Look again at that Cookie Monster geode. In some ways, yes, it’s an excellent likeness. The proportions of the two round circles at the top and the oval underneath, as well as the blue tint of the stone, are very suggestive of the Muppet.

In other ways, though, the two couldn’t be more different. The texture of the rock is smooth and reflective instead of furry and matte, its colors are pale and creamy instead of rich and vibrant, and, most important, the image in the geode is two-dimensional instead of three-dimensional.

Because of the way our minds are wired, though, the rock’s apparent facial features leap out at us, pushing all of those other attributes into the background. If our face-detection systems weren’t so hair-triggered, we might see the differences more than the similarities.

Hacking our perceptions

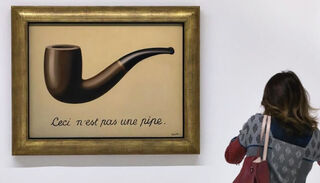

The images we see in art are also illusions. A photograph or painting of a person isn’t really a person. Our visual systems compare the lines and colors we see on two-dimensional surfaces to patterns of line and color we’ve seen in the three-dimensional world, and we can be fooled into thinking we're looking at an object when all we have in front of us is a flat sheet of paper.

Art exploits the mind’s capacity for pattern recognition. It’s an example of hacking our own systems for fun and enjoyment, and it’s just one of many ways we artificially manipulate our environment to take advantage of our biology. We make processed foods that gratify our cravings for salt, fat, and sugar; we compose music out of sounds we find soothing or appealing; we build heating systems and air conditioners to keep our homes at a temperature that feels comfortable.

None of these things have meaning outside the human experience. Something tastes delicious, sounds harmonious, or feels comfortable only insofar as a person perceives it that way. Deliciousness, beauty, and comfort don’t exist in the world around us—they’re qualities of the world within us. They arise from the meeting between a person and the environment.

In just the same way, facelike objects are only facelike from a human point of view.

Whether we see pareidolia as an error or a feature of the human mind, the phenomenon forces us to ask a fundamental question: Can we ever really know the world outside of ourselves? Or is everything we perceive—be it a face, a picture of a face, or a stone that looks like a face—an illusion in its own right, input from outside of ourselves that’s been refashioned by our bodies and brains into something uniquely and beautifully human?