Ethics and Morality

The Pandemic Is a Test of Our Ethics. Will We Pass?

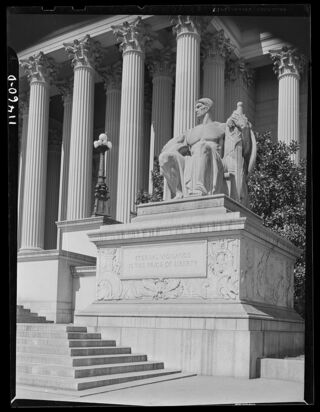

Eternal vigilance, for our health and everyone's, is the price of liberty.

Posted November 15, 2020

It has been noted that the ongoing pandemic has exposed fault lines in our society, in particular with respect to the gaping inequities that divide people along economic and racial lines. The virus has also thrown into relief the realization that Americans do not have a shared understanding of the value of—or even the need for—ethical behavior.

By way of example, this is the case of the music therapist and the geriatric care coordinator. All names have been changed.

Kara is a music psychotherapist who works in the private homes of older adults with dementia. Verbal communication is not possible. Because music offers special access to their emotional lives, Kara practices one of the few approaches to psychotherapy available to them.

Dr. Kurtz is a medical doctor who works as a geriatric care coordinator. She matches families of people with dementia to allied health care practitioners such as Kara.

On March 4, not long after it began to dawn on people that the U.S. would not be spared, Kara wrote these patient notes: “Today Petra was sleepy half the time, otherwise cheerful and laughing. She had a runny nose and the discharge from her right nostril was slightly greenish in color.”

Kara was not wearing a mask on this day. Just five days prior, the Surgeon General of the U.S. told Americans to stop buying masks, stating falsely that they were “not effective.”

Kara continued to treat her client under the assumption that if anyone in the household became sick, Dr. Kurtz would let her know. Ten days later, Kara experienced a brief but urgent gastrointestinal mishap.

In the beginning of April, right around the time that the CDC started recommending face masks in public, Kara walked into her client’s apartment and recognized the smell of bleach. Petra's husband had suddenly dropped dead over the weekend.

Kara checked in with the care coordinator, who insisted that COVID-19 was not the cause of death. Even though Dr. Kurtz had a history of not being completely honest, Kara continued to believe she would get any information vital to her own health and well-being.

By May 15, the safety benefit of masks had become clear to anyone open to hearing it. On that day, Kara wrote to Dr. Kurtz: “Given what we know about this virus, the fact that some aides are not wearing masks feels like a serious risk—to the patients’ health, and also a liability risk.”

Dr. Kurtz finally revealed that tests had showed her patient had enormously high levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Based on her false assumption that people without symptoms could not be infectious, she claimed that Kara was not at risk. This is a logical fallacy known as the appeal to ignorance, often expressed this way: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. And sure enough, within a few weeks it was shown that asymptomatic carriers are in fact a significant vector. (For now, we'll leave aside the fact that the aides not wearing masks went home to neighborhoods with some of the highest infection rates in the city.)

Kara tried to reason with Dr. Kurtz, pointing out that based on the early data starting to come out, she didn’t have enough information to make her determination about risk.

As predicted by the backfire effect, Dr. Kurtz became defensive: “You think you know something because you read reports. You’re not on the front lines in the hospitals like I am. You don’t know what’s happening on the ground.”

Kara's assumptions about the world were crumbling all around. After all, Dr. Kurtz was bound by the Hippocratic oath: First, do no harm. And Kara had grown up believing in Abraham Lincoln’s affirmation at Gettysburg of a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. It was still inconceivable to her that those in authority would take actions that put Americans’ lives at risk.

This pandemic has been a test, and the degree to which so many people in authority have failed that test has sharpened Kara’s ethical consciousness. The experience has solidified the importance of the responsibilities that come with freedom. Her own ethical code of conduct has been reshaped in the forge of the pandemic to include the following:

- In this era of weaponized disinformation, we have a responsibility to manage our information diet.

- We have a responsibility, to ourselves and society, to think critically and control motivated reasoning.

- Ethical behavior means giving priority to peer-reviewed research over one’s own anecdotal experience. This goes for everyone; medical doctors are not exempt.

- Being anti-science is unethical. Willful ignorance is unethical.

- We carry out our responsibility to others by wearing masks. We carry out our responsibility to ourselves by assuming that others are not acting ethically.

- The grown-ups have left the room. No one in authority is going to save us.

- Our society has slipped into a dangerous zone where a sizable number of people believe they have the right to make personal choices that directly lead to the deaths of others.

I think of the inscription, falsely attributed to Thomas Jefferson, that greets visitors to the National Archives in Washington, D.C.: “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” We live in a moment that amplifies the scope of that sentiment. Not only must we be on constant guard against those who want to destroy American democracy, we must also protect ourselves against those who put their own personal liberty above the health, safety, and well-being of others.

I think also of an internet meme that caught my attention this year. It reads: “I don’t know how to explain to you why you should care about other people.” Being ethical includes figuring out how to make the case on a daily basis for why people should care. Our future as a country depends on our ability to communicate that message.