Trauma

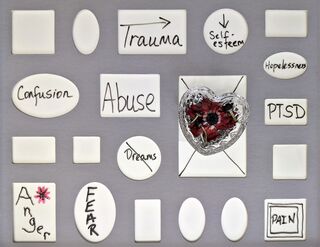

How TikTok and Twitter Get Trauma So Wrong

Understanding mental health misinformation on social media.

Posted September 30, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Trauma is presented in an overly simplistic way on social media, including misinformation about symptoms and poor understanding of diagnosis.

- It is important to understand why mental health misinformation is rife on social media, and to determine accurate sources of information.

- Mental health information on social media should be considered only for psycho-educational purposes, and from qualified professionals.

The marriage of mental health and social media is interesting. Many of my clients use online resources to support their mental health in various ways, including online support forums and psycho-educational Instagram reels. Social media can be helpful in providing easy, bite-sized pieces of information and is a good information-sharing tool. The same positive attributes (ease of use, the capacity to reach large numbers of people) also leaves social media ripe for abuse.

As a trauma-trained therapist, I often see the manner in which trauma (and other mental health disorders) are discussed on social media and am left angered by the misinformation provided.

On social media, trauma is presented neatly and simply in a specific format, usually accompanied by catchy music, or a dance ("if X happens, or if you have Y, then you have trauma").

Examples of this are:

"If you like to watch your favourite show over and over, it may be trauma" and

"If you are a perfectionist, it may be trauma."

Most of the statements presented in this format involve things that may be correlated with trauma, but a correlation is very different from a causal link. Equally, there are a host of non-trauma-related reasons people are perfectionists or watch their favourite shows repeatedly. As an example, I know The Mindy Project is always guaranteed to make me laugh, and I will watch this after a hard day at work to switch off. Making bold statements like these removes all the complexity and the capacity for individual formulation and exploration of a person’s difficulties, and reduces mental health to something entirely mechanistic.

In my work with clients, I always consider a history of trauma, but diagnosis of post-traumatic difficulties is very specialised and involves good clinical history taking, assessment of symptoms, consideration of differential diagnoses (e.g., does someone have PTSD or generalised anxiety disorder?), assessment of the impacts on a person’s life, and consideration of a range of treatment options.

It’s also common for trauma to be conflated with other diagnoses, and for diagnoses to be used incorrectly. For example, I have recently seen posts that state:

"If your partner had an affair, you may have PTSD," and

"If you have ADHD and struggle to do things, remember that you have experienced a lifetime of actual traumas which are now C-PTSD, and that is why you avoid anything which might disappoint people."

Both PTSD and C-PTSD have very specific diagnoses, which involve the need for life-threatening events to occur (for a diagnosis of PTSD; DSM-V), or, "exposure to an event or series of events of an extremely threatening or horrific nature, most commonly prolonged or repetitive events from which escape is difficult or impossible" for C-PTSD (ICD-11).

While the punishment some young children with ADHD may receive may certainly meet the criteria for C-PTSD, this is not the case for all people with ADHD. Neither is worry about disappointing people and task avoidance, a symptom of C-PTSD. It may be a clinical feature for some trauma survivors and some people with ADHD, related to how someone has experienced the events of their life and the compensatory beliefs they have formed after ("if I never hurt or disappoint someone, I won’t be hurt") but is certainly not the case for all people. Statements like these lack nuance and specificity.

Conflating diagnoses in this manner and providing people with misinformation about symptoms is unhelpful and ultimately harmful because it creates misunderstandings about people’s difficulties, may send people down rabbit holes in search of treatment, and often extends and muddies a person’s healing journey. We do trauma survivors (or those with ADHD, or any other diagnosis) no favours by offering neat and appealing—but fundamentally inaccurate—explanations.

It's important to note that the primary purpose of social media is to entertain and generate money. While there are some excellent and skilled mental health professionals with social media channels, the majority of the people who use these channels to share information are not trained mental health professionals; and are instead writers, journalists, content creators, and influencers.

Their task is to grab your attention and to sell you something (a click, a follow, or time spent watching will translate to money) and simple, attention-grabbing statements are the quickest way to do this. It's common for trained mental health professionals to fall into this trap on social media as well; the general structure of most channels does not lend itself well to nuance. Many people have misunderstandings about trauma themselves, and most influencers and content creators do not have the qualifications or skills necessary to sift through complex research and clinical information. While some people have valuable lived experience, lived experience in a specific area itself does not confer an understanding of concepts such as differential diagnoses—unless someone also has specific training. The algorithms of most social media sites are tailored to present clickbait information and to continue to show you information that is like the information you have already expressed interest in, possibly sending you down a funnel where all you see is information about trauma (or ADHD/BPD/autism) until you determine you have this diagnosis.

When working with clients, I always suggest that they use social media for psycho-educational purposes only (i.e., not for specific information about their own diagnoses), that they rely on content creators who have actual qualifications in mental health, and that diagnoses be made by trained professionals. To support people to truly understand, remedy, and manage mental health difficulties, we need to reduce misinformation, and social media is currently failing at this.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., ... & Cloitre, M. (2017). Evidence of distinct profiles of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 trauma questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 181-187.

Friedman, M. J., Resick, P. A., Bryant, R. A., & Brewin, C. R. (2011). Considering PTSD for DSM‐5. Depression and anxiety, 28(9), 750-769.

Szymanski, K., Sapanski, L., & Conway, F. (2011). Trauma and ADHD–association or diagnostic confusion? A clinical perspective. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 10(1), 51-59.

Conway, F., Oster, M., & Szymanski, K. (2011). ADHD and complex trauma: A descriptive study of hospitalized children in an urban psychiatric hospital. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 10(1), 60-72.