Attachment

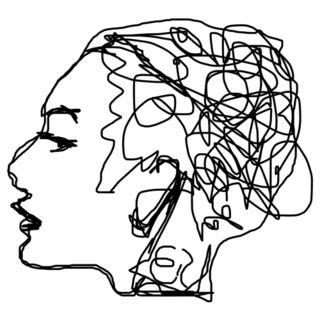

Ghosts in the Machine: Mental Representations Run Our Lives

Subjective internal representations matter more than objective external facts.

Posted January 6, 2020 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

One of Freud’s most important and enduring contributions to our understanding of human psychology is the idea that mental representations matter greatly to our commerce with the world. The core notion is simple: internal representations of people, events, and relationships shaped by past experience guide our present perceptions and reactions as well as our future expectations. We see the world not as it is, but as we are.

An early expression of this idea is found in Freud’s concept of "transference," which is the unconscious projection of feelings and desires, often those formed in childhood, onto a new, current object. In other words, transference involves viewing a present encounter with one person in terms of previous encounters with another. This transference mechanism, according to Freud is “a universal phenomenon of the human mind…and in fact dominates the whole of each person's relations to his human environment.”

Transference happens when something about the present circumstance cues up a past internal representation related to the circumstance. As the psychologist Drew Westen puts it: “The psychoanalytic concept of transference is predicated on the view that people's wishes, fears, feelings, and perceptions of significant others will resemble prototypes from the past… to the extent that aspects of the person or situation activate those mental prototypes.” If something about the therapist reminds me of my father, I will then project onto the therapist qualities and dynamics associated with my relations with my father.

According to Freud, the patient sees in the therapist "the return, the reincarnation, of some important figure out of his childhood or past, and consequently transfers on to him feelings and reactions which undoubtedly applied to this prototype." Transference is a tool of psychotherapy insomuch as it makes visible the client’s unconscious representations.

This idea was developed further by some of Freud’s followers (and dissenters), mostly under the umbrella of object relations theories. In the object relations framework, an object is “that to which a subject relates” (for example, if I love my mother, then my mother is the object of my love). Object representations are the mental images we form of objects, our ways of "possessing" them internally—the memories, expectations, or fantasies we have formed about them through experience. These representations, in turn, guide our commerce with the world.

One early and influential example of how this works is found in the classic work of John Bowlby, the early 20th-century father of attachment theory. According to Bowlby, the child’s early interactions with the world—most importantly the parents—result in the development of an "internal working model"—a set of beliefs about how oneself, the world, and other people are to be regarded. This early template then becomes the filter through which future encounters are assessed. In Bowlby’s own words:

“Each individual builds working models of the world and of himself in it, with the aid of which he perceives events, forecasts the future, and constructs his plans. In the working models of the world that anyone builds a key feature is his notion of who his attachment figures are, where they may be found, and how they may be expected to respond. Similarly, in the working model of the self that anyone builds a key feature is his notion of how acceptable or unacceptable he himself is in the eyes of his attachment figures.”

For example, a child whose parents are unpredictable, cold, insensitive, and incompetent may internalize a working model that sees the self as unworthy of care, the world as a chaotic and dangerous place, and other people as hurtful and unreliable. That child will then move through the world with those ideas shaping how they expect things to go and people to behave.

Attachment theory research has identified three main attachment patterns. Secure attachment (Type B; found in about 65-70 percent of infants) is associated with warm, responsive, and competent parenting and with the most optimal child development outcomes. Two insecure attachment styles, Anxious-Ambivalent (Type C; 10-15 percent) and Avoidant (Type A; 20 percent), are associated with more problematic early relations and suboptimal developmental outcomes.

Interestingly, research has suggested that these early representations relating to parent-child interaction may replicate in adult romantic relations. For example, in one early study, the researchers Cindy Hazan and Phillip Shaver asked their adult participants to endorse one of the following paragraphs relating to their characteristic romantic relationship style:

A. I am somewhat uncomfortable being close to others; I find it difficult to trust them completely, difficult to allow myself to depend on them. I am nervous when anyone gets too close, and often, others want me to be more intimate than I feel comfortable being.

B. I find it relatively easy to get close to others and am comfortable depending on them and having them depend on me. I don't worry about being abandoned or about someone getting too close to me.

C. I find that others are reluctant to get as close as I would like. I often worry that my partner doesn't really love me or won't want to stay with me. I want to get very close to my partner, and this sometimes scares people away.

The researchers found that, quite like with parent-child attachment, roughly 60 percent of adults classified themselves as secure (paragraph B), 20 percent as avoidant (paragraph A), and about 20 percent as anxious (paragraph C). Moreover, some evidence further indicates that early parent-child attachment can actually predict patterns of romantic relations. In other words, those who grew up with a secure attachment to parents are more likely to have a secure attachment style with their romantic partners in adulthood.

The idea that our mental representations shape our movement in the world is useful in other ways too. For example, in my clinical practice, I often see clients who deal with phobic, trauma-induced fears. Understanding how representations work provides useful insight into how those reactions are formed and how they may be treated.

To wit: A client was attacked by a dog when she was a child—a terrifying, traumatic event. She has since been avoiding dogs out of fear. Now, the dog that attacked her is gone, and the client is no longer a child, but if she sees a dog—even a small one on a leash—she’s still inclined to run away in fear. Clearly, her reaction does not correspond to who she is now (a big, strong, knowledgeable adult) or to what the dog in front of her is (tiny, leashed, and trained) but to the "self" and "dog" constructs as represented in her traumatic memory. In this situation, her avoidance of dogs has prevented her from revising these representations, and so when a dog is present, her mind goes back to the old representation created at age four—she is small and helpless; the dog is a scary, violent monster.

Therapy, in this case, will involve exposure to dogs, which over time will allow her to revise her "I-dog" relational schema to represent better who she is now (larger than a dog, stronger, capable of self-defense) and what dogs really are (mostly friendly, non-dangerous).

In my class, while discussing the power of representation, I often ask those students who really love their mothers to raise their hands. I pick an especially enthusiastic responder. Then I tell him, “Your mother is not special!” This, of course, provokes fierce objections. But then I point out that if we ran his mother through a battery of objective tests of skills, personality, values, competencies, and talents, she would come out around average on most of them (as would most of us). Objectively, she’s just another Jane, not at all special. Then I suggest to the student that his mother is indeed special to him, subjectively, due entirely to their unique mutual history. Thus, his idea of "mother" corresponds not to the actual person she is, but to the representation of her in his mind.

That student is all of us.