Relationships

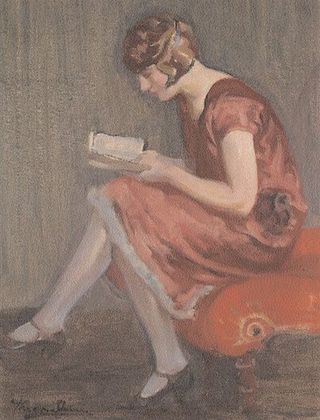

Still Hooked on Books

When the distractions of 21st-century life get you down, books can lift you up.

Posted October 30, 2015

In the summer of 2003, when my nephews were still traveling in car seats, I happened to ride along with them and their parents on a Saturday excursion. After reaching our destination, my brother parked the family van and prepared to unbuckle his sons from their seats.

Unexpectedly, he encountered some resistance from my older nephew, who had been reading a book en route and wanted to continue. This minor conflict prompted an astute observation from his younger brother, who was five at the time. Gazing at his big brother from the confines of his car seat, my younger nephew said to him, with great delight, “Books are really friends for you!”

Hearing this pronouncement, I had to suppress both a happy smile and the urge to shout, “For me too!” For as long as I can remember, books have been my friends and my companions—on train trips and plane rides, on long winter nights and lazy summer afternoons, in brightly lit diners and dim cafés. They are solace, joy, enlightenment and inspiration in tangible, portable form.

My romance with the printed word began when I was still a small child. I distinctly remember a long-ago car trip of my own with my family when I was perhaps four. We stopped for gas, and the gas station attendant noticed me in the back seat with a children’s book in my hands and a serious expression on my small face.

“What’s she doing?” the attendant asked my parents with a friendly smile as he finished pumping gas into our car.

I don’t recall what they said, but I must have felt free to deliver my own response. “I’m reading,” I said emphatically. This made him smile even more—a reaction that I silently and scornfully dismissed, even though my mother was also smiling indulgently at me from her spot in the front passenger seat.

From then on, there was really no stopping me. I read my way through grade school and junior high, gobbling up books one after the other. Titles that still linger in my mind include (in no particular order): “Beautiful Joe,” “King of the Wind,” “My Friend Flicka,” “The Pink Motel,” “Island of the Blue Dolphins,” the “Sue Barton” nurse novels, “Little Women,” “Pride and Prejudice,” “The Diary of Anne Frank,” “Up the Down Staircase” and several paperbacks my mother read and passed along to me, including “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

High school brought more sober fare, including the searing “Manchild in the Promised Land,” “Soul on Ice,” “Siddhartha” and “Crime and Punishment.” My teachers assigned some of these books, and some I found on my own by haunting an independent bookstore in a local shopping center. But my fate for the next several years was sealed when I encountered “Romeo and Juliet” and “Macbeth” in an English class and fell in love with the musical, magical language of William Shakespeare.

I think it was my thoughtful brother who, for one of my birthdays in high school, gave me a Viking paperback “Portable Shakespeare” that had seven complete plays, all of the sonnets and selections from 25 of the Bard’s other plays. This compact book became one of my most treasured possessions, and I am proud to say that I still have it, although the pages are now dog-eared and I had to tape the spine after it finally split apart from years of use.

As a college English major, I extended my romance with Shakespeare and other British writers. I also studied contemporary American poetry, and even tried my hand at writing poems—although, thankfully, none of my attempts survive in published form. As a graduate student in English literature, I continued my Shakespeare studies and fell head over heels for Geoffrey Chaucer, who still seems to me one of the most acute observers of humankind ever to put pen to paper.

After three years in graduate school, it began to dawn on me that, much as I loved reading and writing about literature, I might not love the life of a full-time academic that I was preparing myself for. I left graduate school, moved to New York, and in the process of “finding myself,” started reading the works of the many brilliant women writers I had neglected in college and graduate school, including the novels and essays of Virginia Woolf.

Two years later, I headed back to school again—this time to learn to be a journalist. I hoped this profession would allow me to combine the love of writing that reading had instilled in me with my desire to be of service in the troubled world of the here and now.

Journalism proved to be a much better career choice for me. But though I left the university life behind, I never abandoned my love of reading. I lived a somewhat nomadic existence for many years, with moves to New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and Honolulu. But I insisted on bringing my boxes of books with me on every move, and as the years passed I continued to discover authors and books to add to my collection.

In 2003 I returned from Honolulu to Pennsylvania, where I had grown up, to help take care of my mother, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. My books made the trip back across the Pacific Ocean, and they helped sustain me during several hard years when my mother’s declining health was my top priority.

Since my mother’s death in 2009, I have tried to step up my reading and also branch out from the novels and short stories that remain among my favorite categories to read more biographies, history and contemporary non-fiction about pressing social issues. And in the back of my mind, I am hatching a plan to delve back into Shakespeare—both the plays I know and love and those I never quite got around to reading, such as “Antony and Cleopatra.”

In a world where information is increasingly transmitted via 140-character tweets, Facebook posts and pundits of all political persuasions on cable news shows, I realize I may seem hopelessly behind the times. But still I persist, encouraged in part by the dark vision of a prolific writer of science fiction—a genre that, ironically, I have largely ignored in my decades of burying my nose in books.

Ray Bradbury’s 1953 dystopian novel “Fahrenheit 451” takes place in an oppressive future where books are banned and people spend their days staring at mindless entertainment on wall-sized electronic screens. Acting on tips from neighbors, government “firemen” search the homes of people who are hiding books. The fireman’s job is not to put out fires but to start them by soaking the books in kerosene, lighting the kerosene, and thus reducing the home and the books in it to ash. (Fahrenheit 451 is the temperature at which paper burns.)

I saw the film version of “Fahrenheit 451” when I was in college, several years after its original 1966 release. In one particularly vivid scene, the firemen invade the home of a middle-aged woman and discover her sizable hidden cache of books. Before they can set fire to the books, however, she does so herself. The woman, dressed in a cardigan, wool skirt and pearls and looking like a beloved high school English teacher, stands on the flaming pile of books and burns with them, preferring this excruciating death to life in a world without books.

I distinctly remember watching that scene in horrified fascination in college and thinking to myself, “That’s me in 40 years.” What I didn’t know then was how much the world in 40 years would come to resemble the world of “Fahrenheit 451”: homes with giant electronic screens on the walls, a population anesthetized by watching them for hours, and a segment of our political leaders seemingly intent on encouraging ignorance instead of combatting it.

In his forward to the 1993 40th anniversary edition of “Fahrenheit 451,” Ray Bradbury made a chilling observation. He recalled “…a prediction that my fire Chief, Beatty, made in 1953, halfway through my book. It had to do with books being burned without matches or fire. Because you don’t have to burn books, do you, if the world starts to fill up with non-readers, non-learners, non-knowers? If the world wide-screen-basketballs and footballs itself to drown in MTV, no Beattys are needed to ignite the kerosene or hunt the reader. If the primary grades suffer meltdown and vanish through the cracks and ventilators of the schoolroom, who, after a while, will know or care?”

So my advice to you, gentle reader, is this: Visit a nearby library or bookstore, and borrow or buy a book or two today. You will make friends for life who will never let you down. You will have the thrill of travel without leaving home. You will gain knowledge, possibly increase your vocabulary and—just by letting your eyes travel down a page of print and your mind reflect upon what you are reading—commit a daring and radically empowering act. Readers of the world: Unite! You have nothing but ignorance to lose and a world of knowledge and insight to gain.

Copyright © 2015 by Susan Hooper