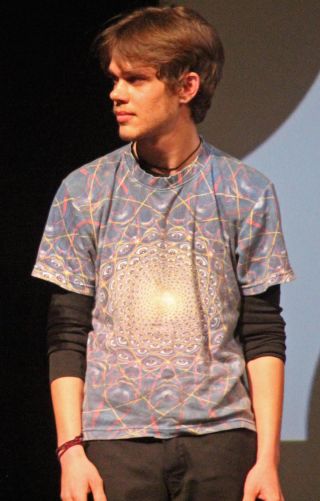

It is awards season, and Boyhood, directed by Richard Linklater, has already added six Oscar nominations and three Golden Globe wins to what will undoubtedly be a large basket of honors. The movie is remarkable because the fictional action of the story takes place over a twelve-year period, and the film itself also took twelve years to shoot. The core characters of the story were played by the same people over the entire period of filming, with each actor aging in unison with the fictional plot line. Most dramatically, the seven-year-old Ellar Coltrane was cast as the central character, Mason Evans, Jr., and as Boyhood’s coming of age story unfolds, the audience witnesses a cute first-grader turn into a gawky but appealing high school graduate. In this case, the physical transformation of these years of rapid growth was not accomplished with makeup, multiple actors, or computer-generated imagery. Aging happened the old fashioned way: by waiting for time to do its work. In the course of two hours and 45 minutes of viewing time, the audience witnesses the effects of twelve years on the faces and bodies of the four main actors: Coltrane, Patricia Arquette, Ethan Hawke, and Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, who was eight-years-old when filming began.

Ellar Coltrane plays Mason Evans, Jr.

Watching this movie is a remarkable experience because, once the viewer knows the backstory of the production process, she looks at the film with an inexorably altered eye. I liked Boyhood for many reasons, but it was a truly unique experience to watch each new change in Coltrane and the other actors as the story followed its linear path. The effect was dazzling, and somehow, it never felt gimmicky or contrived.

Now that the film will be getting more attention, it is worth considering why viewers admire it so much. I suspect very few people watch the film without knowing (or figuring out) the way it was created, but if there are such people, the psychologist in me would love to talk to them. What if no one had ever told you that the actors were filmed over a long period of time? What if you assumed the apparent aging of the fictional characters of Boyhood was accomplished using the usual Hollywood methods: makeup and multiple actors? Would you like the film as much? Would you consider it to be as worthy of awards?

The mind of the audience member is a curious thing. At the outset we are asked to engage in what Samuel Coleridge called “the willing suspension of disbelief.” The artist creates a world that doesn’t exist, and we agree to go there, inhabit it, and accept its sometimes unusual rules and premises. In Lord of the Rings or Star Wars or Harry Potter, science fiction and supernatural happenings are accepted as part of the bargain. However, when bad acting or bad writing reminds us that the fictional world is not real, the spell is broken and we are disappointed. In The Art of Fiction, novelist John Gardner said the writer’s task was to create a “vivid and continuous dream,” and if the writer draws attention to herself rather than to the story, she risks waking the reader from the dream.

Cider House Rules movie poster

But as viewers, we are not entirely unconscious dreamers. When we sleep we are often able to stand apart from the action of our dreams and recognize that the chaotic story we are witnessing is not real. This kind of double consciousness is always true of our experience of art. When we watch or read or listen to a fictional story, we know it is a fiction. Furthermore we come to our position as audience member with certain assumptions. For example, live theater is judged differently than a movie of the same story. I have had the somewhat unique opportunity of experiencing John Irving’s The Cider House Rules as a play (an adaptation performed over two consecutive nights), as a feature film, and as the original novel. I liked the novel, but I loved the play. Furthermore—and more to the point—I had a gushing response to the live production, but the movie left me cold. These somewhat similar art forms produced very different responses.

There are several reasons why I might not have liked the movie as much as the play. For example, there may have been an order effect: I saw the movie after I’d seen the play. In addition, the two-night theater production retained more of the original story than the much shorter film—despite a screenplay written by Irving himself. Furthermore, I am sure the live performance benefited simply from being live.

When you are at a play, no matter how swept up in the action you become, you are very aware of how the play has been produced. The story is being created for your benefit before your very eyes. The staging has inherent limitations of place and action, and the actors do not get a second chance to impress you. Even when their work does not achieve the smooth perfection of most film performances, we give the actor credit for doing it live. In contrast, movie audiences know that filmmakers can employ a variety of tricks to be certain the product we see is as good as possible. As a result, we are often tougher graders of films than of plays.

Whether the performance is live or on film, our knowledge of an actor affects our judgment of the work. In Foxcatcher most of us are familiar with Steve Carell’s normal appearance and voice and his previous work in comedies. The attention he has gotten for the role of the wrestling enthusiast, John E. du Pont, owes something to this prior knowledge of his very different past performances. Daniel Day Lewis and Meryl Streep have earned their reputations (and many Oscars) by transforming themselves into characters that are far afield of their prior roles and the people we know them to be offstage.

Steve Carell in Foxcatcher

Even when we don’t know the actor well, we give credit for substantial effort that is visible on stage or on screen. Eddie Redmayne is not yet familiar to most American audiences, but his Golden Globe winning and Oscar nominated role as Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything displayed a physicality that—along with an otherwise winning performance—has earned him deserved acclaim.[1] On the one hand, we know the transformation is artifice. But if it is done skillfully, the dream remains continuous, and we give the actor credit for an effective illusion.

This leads to an interesting conclusion. Without question, we must sometimes—perhaps often—be judging incorrectly. If we believe we are justified in altering our assessment of a work or a performance on the basis of the effort or “stretch” involved in creating it, then what if we can’t tell? What if the actor is unknown to us and is remarkably skilled at her craft, stretching mightily and seamlessly without our knowing? It is also possible that something that appears easy to us is actually very difficult for the actor. Imagine, for example, an actor who has a physical disability but takes on a role that requires her to appear able bodied? If she achieves a remarkably skilled illusion, we might miss entirely that she is not usually or consistently able to perform in this way.

In the case of Boyhood, there is no missing the effort. Once we are told what went into the production, we cannot remove the effect of that knowledge from our assessment of the film. The value we place on effort and stretch is similar to any other performance, but the specifics of this film are unique. Perhaps we would see Boyhood differently if no one had ever taken us behind the curtain, but once the manner of creation is revealed, that shared secret becomes an integral part of our experience of the dream.

Jerry Mathers as The Beaver

There is another interesting feature of the Boyhood phenomenon. It is not entirely foreign for audiences to watch actors age with their characters. I grew up watching the weekly television series, Leave it to Beaver and My Three Sons, both of which had child actors who returned year after year, aging in real time. More recently, during the ten years between 2001 to 2011, viewers watched Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson—the actors who played Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger, respectively—age with each successive Harry Potter movie installment. But in these cases, the audience experienced time passing in parallel with the action of the story. In the case of the Leave it to Beaver, we imagined the episodes occurring in the present, and when we tuned in each subsequent year, it made sense that—like us—Beaver and his brother Wally would be a year older. In a similar fashion, the Harry Potter movies were separated in time. The characters aged as we did. Perhaps at a somewhat slower pace, but aging over time nonetheless, while we moviegoers were away from the theater doing other things.

All of these cases are examples of something we might call age-concordant casting. Jerry Mathers, the child actor who played The Beaver, was plausibly the same age as the character he played. Both Mathers and The Beaver aged over time, but at all times, the actor’s age approximated the age of character he was playing.

Eddie Redmayne as Stephen Hawking

In Boyhood, age-concordant casting applies for the four central roles, but in this case, the story is a twelve-year-long family saga collapsed into a single two hour and forty-five minute film. When viewing a series, such as Leave it to Beaver or the Harry Potter movies, we periodically check in on a story that unfolds in something much closer to real time, and the aging of the actors remains concordant with the characters they play. In contrast, Boyhood is viewed in a single sitting. The story covers many years, and at all times the actors are age-concordant with the characters they play. In this case, we are aware that the compression of time has been accomplished by a very long production schedule and the recording of scenes throughout a twelve-year period.

As audience members—consciously or unconsciously—we bring all of this knowledge to our assessment of the film. It is unlikely we have seen anything like it before, and the unique experience of watching people age on screen is compelling. Delight in this transformation, combined with our knowledge of the effort that went into creating it, produces a unique movie experience.

[1] For an interesting argument about the appropriateness of casting an able-bodied actor in this and similar roles, see this article in The Guardian by Frances Ryan.