Identity

How Stable Is the Personal Past?

This research observed how life stories develop throughout the lifespan.

Posted November 9, 2017

Have you ever wondered what your life story would look like if you told it several times, at different moments in your life? Which life events would you keep in or leave out? And for what reasons?

According to narrative psychology, a person’s life story is not a mere chronicle of the facts and events of a life, but rather the way a person picks apart or weaves together those facts and events internally to create personal meaning. This narrative becomes a form of narrative identity, in which the experiences people choose to include in the story, and the way they tell it, can both reflect and shape who they are.

The most comprehensive form to present such narrative identity is presumably one’s entire life narrative, starting at the moment of birth, spanning the entire life span until the narrator’s present moment, and maybe including an outlook on the future. A life narrative does not just convey what happened, it explains why it was important and what it means for who the person is, for who she or he will become. Given that life narratives are informing our sense of self and constitute a part of our identity, they should exhibit at least some stability. After all, people would want some stability in their sense of self, wouldn’t they? So would they hold on to a life narrative, at least to some extent? If so, how stable is the personal past and does this change with age?

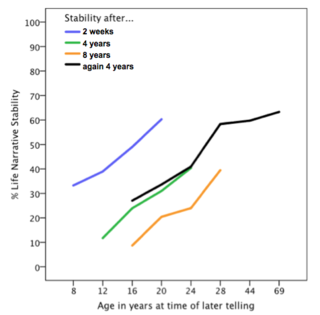

Driven by these two questions, in the longitudinal MainLife study conducted at the Goethe University Frankfurt, we asked people to tell us the story of how they became the person they are today – and we asked them the same question several times. More specifically, Tilmann Habermas started this longitudinal study in 2003 with four groups of 8-, 12-, 16- and 20-year olds who delivered their life narratives two weeks apart. At the next measurement time, in 2007, these four age groups were interviewed again, and two adult groups aged 40 and 65 years were added. In 2011, most of the participants came back for another interview, enlarging the cohort's sequential age range from 8 to 69 years.

Altogether, we had 523 entire life narratives, told throughout eight years but with different time intervals (Figure 1). To detect their stability, we compared which events were related repeatedly and which were not. Further, we analyzed whether normative events that biological development makes happen or that society expects to happen at a certain age—such as high-school graduation, first kiss, or wedding—would actually be more stable than idiosyncratic events, such as traveling.

We found that stability of life narratives decreases the longer the time span between two interviews, but increases with age. While 8-year-old Tim barely remembered what he had said four or eight years earlier and repeated only about 10 percent of his earlier life narrative, 24-year-old Tina repeated about 30 percent of her earlier life narrative. With older age, life narrative stability increased even more, so that our 69-year-old participants repeated about 70 percent of their earlier life narratives from four years earlier.

Yet these percentages do not say much without looking at which life events had been narrated. We indeed found normative events to be more stable than idiosyncratic events. Apparently, life events that normatively happen at a certain age and mark the beginning or end of life phases are told repeatedly, presumably because they serve to structure the life narrative. However, idiosyncratic life events also showed a certain stability, suggesting that some experiences are transformed into stable pillars of people’s narrative identity.

Developing a relatively stable life narrative is part of human development. Once we have figured out how we became the person we are at that moment and where we are going, we seem to at least partly hold on to it, which helps give us a stable sense of self. We recognize and present ourselves not only in the life story we tell but also in the life story we repeat.

References

Köber, C., & Habermas, T. (2017). How stable is the personal past? Stability of most important autobiographical memories and life narratives across eight years in a life span sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 608–626. http://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000145