Memory

Does Loss of Memory Equal Loss of Emotion?

Memories and emotions are deeply intertwined with one another.

Posted April 27, 2024 Reviewed by Pam Dailey

Key points

- Recall of a memory often brings up the emotion experienced when the memory was formed.

- Study subjects with memory loss retained emotions even after forgetting the experience that had evoked them.

- Loss of memory does not mean loss of emotion.

Emotions and memories go hand in hand. Many researchers have reported that memories of emotional events are easier to recall than memories of everyday events, like what you had for breakfast two days ago or whether or not you brushed your teeth today, despite the fact that these ordinary tasks are quite literally ones we perform every single day.

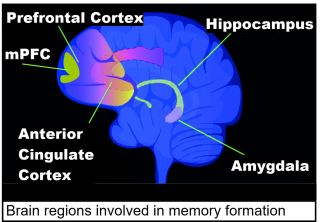

Neurologically speaking, there is a clear link between emotion and memory. Emotion affects the formation of a memory because emotions are both physiologically and cognitively arousing. This arousal activates the amygdala and the hippocampus, both of which are involved in memory formation and consolidation. So emotional memories are stored more effectively than are memories for the everyday event. Memories for emotional events tend to be vivid and detailed. These memories persist over time, along with memory for the valence (positive or negative) of the emotion that we felt when the event happened (Dolcos, LaBar, and Cabeza, 2004).

Notice that these especially vivid memories for emotionally charged events involve a clear and vivid memory for the cause of that memory. Most of us can easily remember where were we when the towers fell, who was with us, and our emotional reaction to that event. Memory of the event that caused the emotional reaction is intact and intimately linked to the emotions the event evoked.

So it is clear that emotions can and do influence memory. But does it work the other way around? If memory is impaired, what happens to emotion? In 2010, Feinstein, Duff, and Tranel examined memories for emotional events in a unique group of patients with severe anterograde amnesia. Anterograde amnesia is the inability to form new memories. Feinstein, et al were curious about whether the “sustained experience of an emotion was dependent upon… intact, declarative memory for the event that caused the emotion.”

Feinstein, et al. showed their participants, both amnesic and control, film clips that had been shown to reliably induce emotional reactions of sadness or happiness in previous studies. They then measured memory for details from the films in their participants as well as their self-reports of emotional state. Emotion was assessed before viewing the film (baseline) for both groups and then immediately after viewing, 10 minutes after viewing, and finally 30 minutes after they had seen the films. Memory for details from the film clips was measured approximately 6 minutes after participants had seen the clips.

There was a significant difference in declarative memory for details from the film between control and amnesic participants. The control participants remembered roughly 30 details from the films while the amnesic subjects remembered about five details on average. Emotion ratings measured as change from baseline fell to almost baseline levels in the control group. However in the amnesia patients, emotion ratings remained elevated even 30 minutes after viewing the films—despite the fact that memory for what had induced the emotion had all but disappeared by this time.

The valence of the emotion induced by viewing the film clips did not affect the outcome. Both sadness and happiness levels remained elevated long after memory for what had created these emotions had faded away.

In 2014 Guzman-Velez, Feinstein, and Tranel examined the link between memory and emotion in a group of patients suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), a far larger subset of the population than are severe amnesia patients.

Using the same experimental paradigm that Feinstein, et al used in 2004, they induced feelings of happiness and sadness in a group of patients suffering from AD and in healthy control individuals matched for age, sex (they tested both males and females), and education. And they found, once again, that despite not being able to recall the details of the films they’d watched, for AD sufferers’ emotional reactions remained elevated well beyond the point at which the details of the films, either happy or sad, had faded away. They likened this disassociation between declarative memory and emotions to being “stuck in a mood and you can’t remember why.”

These kinds of results may have implications for treatment and help for people suffering from AD. The actions caretakers and family have toward AD patients may have unintended consequences. Even though AD patients may not remember the specific actions that created an emotional response, the emotion itself may linger for quite a while. Perhaps “adopting an attitude of acceptance and giving the patients … positive affirmation can potentially induce prolonged states of positive emotion…while minimizing…instances of noncompliant and aggressive behavior.”

References

Dolcos, F., LaBar, K.S., and Cabeza, R., (2004). Interaction between the amygdala and the medial temporal lobe memory system predicts better memory for emotional events. Neuron, 42, 855-863.