Big 5 Personality Traits

A New Big Five for Psychotherapists, Part II

CAST offers psychotherapists a new big five.

Posted April 6, 2017

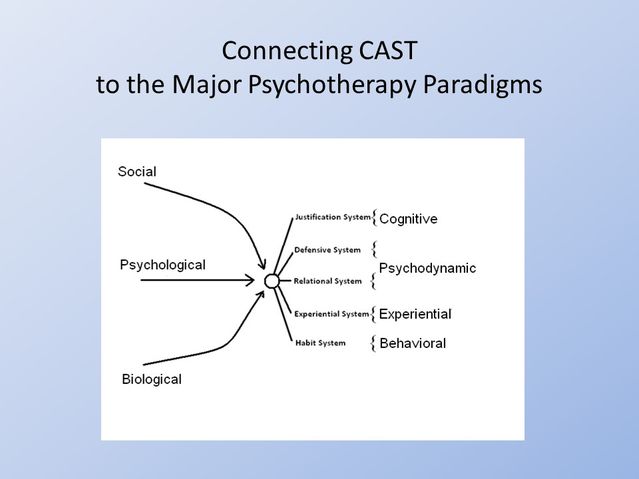

Character Adaptation Systems Theory (CAST) was recently published in the Review of General Psychology. CAST is an outgrowth of a new unified theory of psychology (UT) that sets the stage for a unified approach to psychotherapy (UA). It achieves this by reframing the key insights of the four major approaches to psychotherapy as emphasizing different systems of human psychological adaptation.

Part I of this two-part blog series provided the background to understanding how CAST changes the field of psychotherapy. An analogy to medicine was made and readers were asked to engage in a thought experiment and imagine medical specialists squabbling over which biological system was the key to overall health. We saw how silly it would be if cardiologists debated with those in orthopedics on whether the circulatory system or the skeletal-muscular system was central to overall health. The reason this sounded ridiculous is that we have a relatively unified picture of human biology and recognize these as different subsystems that connect to a whole.

CAST posits that the current situation in psychotherapy is akin to this thought experiment for the field of medicine. If we look at the major paradigms we see that they have particular elements of psychological adaptation that they tend to focus on. Psychodynamic theory focuses on key relationships and early attachments and how people defend against threatening material. Cognitive therapy focuses on how folks develop verbal interpretations, expectations, and attributions for who they are and how the world works. Behavioral therapies focus on basic learning and how habits are formed via associations and consequences. Humanistic therapies focus on emotions and perceptual experience and the congruence between our true selves and our social selves.

Given that the field is arranged in paradigms, we can step back and ask which one of these insights is central to human psychological health. That is, where do we need to focus our attention to foster human well-being? Is it on habits and lifestyles? Or emotions and emotional functioning? Or human relationships and attachments? Or defenses and coping? Or attributions, beliefs and values, and human narratives? Let’s extend our analogy with our medicine thought experiment, and imagine a conversation between different adherents to these major paradigms.

“The key to psychological health is learning,” says the behavior therapist. “We just need to pair the necessary associations and consequences with the right stimuli and effective functioning in the right environments”.

“No, that is not right. Things are not in and of themselves, but rather are how people interpret them. Thus, we need to look at thoughts, explanations, and attributions, and alter maladaptive thinking patterns into adaptive ones,” says the cognitive therapist.

“Not at all,” says the psychodynamic therapist. “Conscious thoughts just represent the tip of the iceberg. We have to help people gain insight into their defenses and help them understand how their current patterns of being connect to early attachments.”

“You are all wrong,” says the neo-Humanistic emotion-focused therapist. “Emotions are the key. We need to focus on how to coach folks on relating to and processing their emotions in a healthy and adaptive way.”

Instead of being difficult to imagine as was the case when we did this for the medical specialties, this debate is essentially the way the field is currently arranged. The UT argues that the lack of a clear, comprehensive picture of the science of human psychology caused certain gurus (like Freud, Rogers, and Beck) to emerge with “key insights” about human adaptation and develop training models and therapies for dealing with those issues. However, CAST suggests they were only looking at a piece of the puzzle, and if you translate their insights as mapping onto different systems of character adaptation, one can see this in a very clear light.

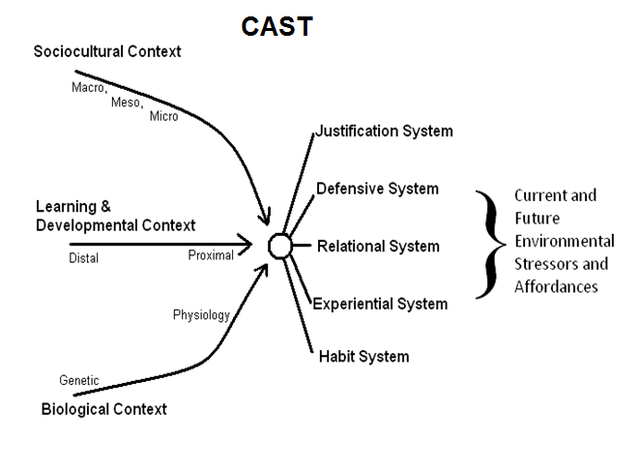

CAST encourages psychotherapists to ask: What if instead of these ideas being anchored in wholly different paradigms, the truth is closer to the fact that each major paradigm largely focuses on a particular system of psychological adaptation? Specifically, CAST argues that there are five systems of human psychological/ character adaptation. Much of human psychology is understandable through these systems, especially when we consider these systems as existing in biological, learning and developmental, and socio-cultural contexts. Below the five systems are briefly described. The subsequent section makes the direct linkages with the major paradigms.

All of this sets the stage for a radical transformation in how we think about the organization of the field. The implication is that the horse race between the major paradigms in psychotherapy is very much misguided. Instead, we need to step back and see that each paradigm is really just focused on a “piece of the elephant”.

The Five Systems of Character Adaptation

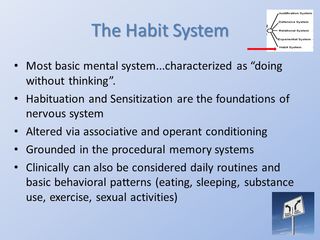

The Habit System

The first and most basic system in CAST is called the habit system. It consists of sensorimotor patterns and reflexes, fixed action patterns, and procedural memories that can operate automatically and be produced without any conscious awareness. As reviewed by Duhigg (The Power of Habit, 2012), habitual responses can usefully be divided up into three elements that form a loop. First, there is a stimulus or cue, which is followed by an enacted procedure or response, and finally, there is a rewarding consequence that functions to embed the response cycle in the mindbrain system. This is the habit loop. One of the more remarkable features of the habit system is that virtually anything can become a habit, so long as the procedure has certain fixed elements in it. A classic example of how relatively complicated patterns can become habituated is found in learning to drive a car. New drivers often experience an overload of incoming information when first sitting behind the wheel. Learning how to adjust the seat and mirrors, the correct angle at which to put the key in the ignition and the right way to turn the wheel when backing up all require intense conscious control the first few times they are attempted. However, the sequence becomes automatized in the habit system over time, such that advanced drivers can enact all the above without any self-conscious thought.

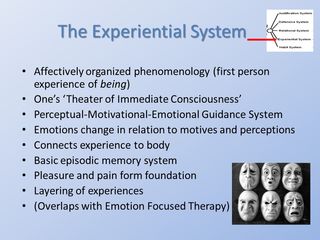

The Experiential System

The second system in CAST is the experiential system, which refers to the nonverbal perceptions, motives, and drives, and emotional feelings states that make up the subjective “theater of experience”. Examples of experiential phenomena include seeing red, being hungry, and feeling angry. Such “first person” mental experiences are emergent phenomena that arise from waves of neural information processing (see here). The UT frames the experiential system as linking perceptions, motivations, and emotions via a “control” formulation whereby objects and events are categorized and made meaningful by perceptual processes (i.e., what is it, where is it) and are then integrated and referenced against motivational goal templates (i.e., drives to approach or avoid certain states) which then result in action-orienting emotional response tendencies. This is called the P – M => E formulation, and is described in more detail here.

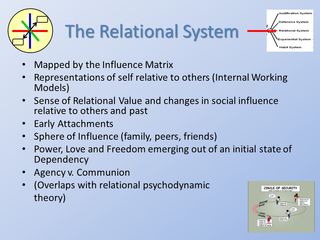

The Relational System

The third system in CAST is the relational system. It is conceptualized as an extension of the experiential system that emerges both as mentation becomes more complicated (i.e., as animals evolve with increasing cortical functioning) and as animals become more social (we are talking especially here about social mammals like dogs and primates). The relational system refers to the social motivations and feelings states, along with intuitive internal working models and self-in-relation-to-other schema that guide social mammals in general and people in particular in their social exchanges and relationships. It is important to note, then, that the relational system as considered here is not dependent upon verbal processing, although, of course, in humans, verbal processing can dramatically influence the operations of the relational system. The UT offers the Influence Matrix as a map of the human relationship system.

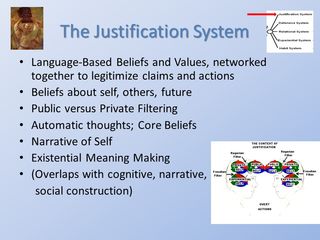

The Justification System

The justification system is the fifth system of character adaptation; however, it is useful to explain this system and then proceed to describe the fourth system, the defensive system, as the shape of the latter is influenced by the organization of the former. The justification system is the seat of verbally mediated thoughts and symbolic reasoning. It is organized into language-based systems of beliefs and values that an individual uses to determine which actions and claims are legitimate and which are not, to give reasons for one’s behavior, and ultimately to develop a meaningful worldview. Although individuals can learn how to engage in analytic reasoning via the justification system, the formulation provided by the UT is that the justification system is first and foremost a motivated reasoning system, one that is guided by (although not necessarily dictated by) nonverbal drives, goals, and intuitive frames, and is functionally organized as a reason giving system, rather than a purely analytical reasoning system.

The UT characterizes the human self-consciousness system as being unique in the animal kingdom. It works to develop “justification narratives” that allows an individual to navigate the cultural beliefs and values that legitimize actions (what sociologists call “social facts”). A feature of the system is that it seeks a “justifiable state of being”, which allows us to understand the nature of the fourth system in CAST.

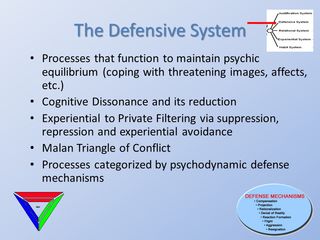

The Defensive System

The defensive system is the fourth system in CAST. Consistent with the UT formulation of the justification system, refers to the ways in which individuals manage their actions, feelings, and thoughts, and specifically the way individuals shift the focus of conscious attention to maintain a state of psychic equilibrium in times of threat or insecurity. The defensive system is the most diffuse of the character adaptation systems; however, it can nevertheless be specified by examining how images, impulses, cravings, and desires from the nonverbal systems (i.e., habit, experiential, relational) are integrated (or not) with the individual’s self-conscious justifications for being (see here for a more detailed blog on the defensive system). We reviewed the justification system prior to delving into the defensive system because the justification system seeks “equilibrium” such that the individual is in a “justified state of being.” A justified state of being is one that is secure and legitimate and thus individuals must manage thoughts and situations that suggest otherwise. Although there are a number of things that people are defended against, we can identify five broad domains, including: (a) death and the idea of death, (b) threats to one’s worldview and meaning making systems, (c) threats to one’s relationships with others, (d) threats to self-esteem or self-concept, and (e) painful feelings or memories. For an example of how the defensive system works, consider an adolescent who grows up in a household that is hostile toward homosexuality, but starts to experience homosexual urges. Here the justification system (i.e., the explicit belief that homosexuality is wrong) comes into conflict with the experiential system (i.e., sexual arousal in response to homoerotic material).

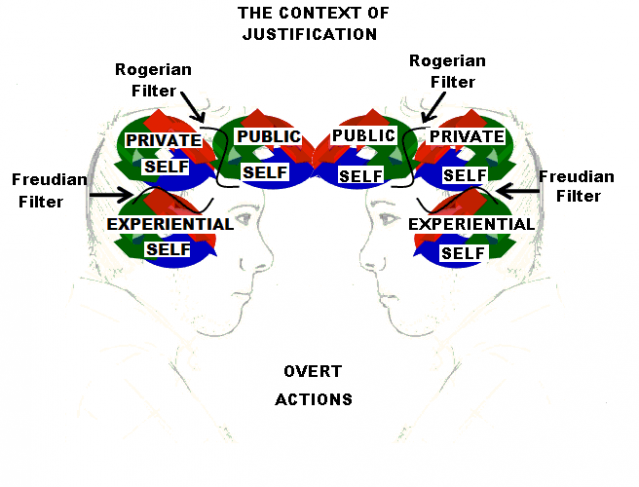

The combination of these systems of adaptation can be drawn together into a relatively straightforward tripartite model of human consciousness, depicted below. This shows the experiential self, the private narrator and the public self (that which is shared and displayed). It also shows key filters. One filter is between the experiential and the private self. This is the “Freudian Filter”, which corresponds to the Malan Triangle of Conflict. The second is the “Rogerian Filter”, which corresponds to how individuals manage the tensions between what they share with others and what they do not (i.e., the extent to which they are authentic on the one hand or are lying or feel like imposters on the other).

Lining Up the Big 5 of CAST with the Four Major Paradigms

CAST posits that the different traditions emerged at a time when there was no way to see the whole and they gravitated to particular systems to simplify the complexity of human functioning. This section reviews the way the major systems of individual psychotherapy line up with the five systems of character adaptation. The time is now to let go of the paradigms and start to work from a picture of the whole.

The Behavioral Tradition Aligns With the Habit System

The general emphasis in traditional behavior therapy is not on one’s inner experience or, traditionally, even thought processes. Rather, the focus is on overt behavior and the environment and how the individual responds to certain stimuli (in associative conditioning) or is rewarded or punished for certain actions. The goal of traditional behavior therapy is either to shift environmental cues, alter response patterns, or shift reward structures with the goal of breaking maladaptive habit loops and replacing them with new and more adaptive learned patterns. Virtually all behavior therapy approaches, from desensitization and flooding to response costs and token economies, can be understood as emphasizing the need to alter the antecedent cue, the response, or the consequence in particular environmental contexts. These elements line up directly with the habit loop. Associative conditioning explores the relationship between the cue (stimulus) and routine (response), whereas operant conditioning explores the relationship between the routine and the consequence.

The Humanistic Tradition Aligns With the Experiential System

Perhaps the central insight from the experiential/neo-Humanistic perspective is that there are two ways of knowing—(a) conceptual (knowledge by verbal, analytic description) and (b) experiential (knowledge by direct experience). Experiential or emotion-focused therapies emphasize the importance of using the latter form of knowing when facilitating patient change (in contrast to cognitive therapies, which emphasize the former). Carl Rogers was central to experiential approaches because of his general emphasis on phenomenology and the utilization of deep empathy to access aspects of the “true self” that had been hidden, split off, or poorly integrated as a consequence of fear from judgmental others, or internalized self-judgment.

Currently one of the most prominent forms of experiential therapy is emotion-focused therapy, which has as its central focus understanding the way emotions organize experiential consciousness and the process by which such emotional processing is generally adaptive or maladaptive. The central thrust of EFT is that primary emotional responses signal key information about core needs (such as the need to be loved or competent). If an individual is attuned to those needs and arrives at those feeling states and integrates what the feeling is communicating into their higher self-consciousness, then one is in a much better place to achieve mental and relational harmony. However, if the primary adaptive emotional response is blocked because it is deemed threatening or confusing or unacceptable and either ignored or replaced with a secondary feeling (e.g., rather than feeling hurt about being rejected, the individual becomes angry at the unfairness of it and says he does not care), then there will be significant disharmony and misalignment between the core needs and emotional expression. In EFT, therapists work to coach clients to understand how to connect to their primary adaptive feelings and work through unfinished emotional business, in which they historically were not able to process their primary feelings.

Modern Psychodynamic Approaches Align With the Relational and Defensive Systems

The key insights of modern psychodynamic approaches are (a) our motivations and needs are deeply relational in nature and (b) that much of our motivation lies outside our conscious awareness and that we are defended against threatening thoughts and feelings. To understand point (a), it is crucial to recognize the “relational turn” that psychoanalysis has taken in the past several decades. For example, most psychodynamic theorists and therapists now think primarily in terms attachment theory, drives for power and love and subconscious relational schema, scripts, and expectations that people use to navigate the social world. The map of the relational system provided by the Influence Matrix lines up quite directly with these emphases.

A quick and straightforward way to understand (b) is to consider the Malan Triangle of Conflict. This provides a schema for how disturbing or problematic images, impulses or affects trigger a “signal anxiety” because they feelings are dangerous. This signal anxiety then activates the defensive system in an attempt to avoid the threat and return to a state of equilibrium. The Malan Triangle of Conflict explains why some material is readily accessible to consciousness, whereas other material, especially that which is threatening to one’s real or perceived status or identity, is often avoided, repressed or filtered out. The model is very consistent with the defensive system as existing “in between” the subconscious experiential/relational systems and the self-conscious justification systems. Moreover, the catalogue of defense mechanisms delineated by psychodynamic theorists serves as an excellent starting point for understanding the structure and organization of the defensive system.

Consistent with these claims, the modern psychodynamic therapist generally seeks to enter the patient’s relational system and restructure it through a corrective emotional experience and through insight that is achieved via the interpretations made by the therapist. In sum, the psychodynamic approach attempts to foster psychological adaptation via understanding an individual’s character structure via the lenses of relationship processes and defense. Therapy is structured on gaining insight into those processes and fostering adaptive correction of attachments and associated feelings in the context of a healing therapeutic relationship.

The Cognitive Approaches Align With the Justification System

Major forms of traditional cognitive therapy offer a systematic approach to becoming aware of, assessing, and changing one’s justification system to function in a more adaptive way. For example, traditional Beckian cognitive therapy works by teaching individuals how interpretations and self-talk feedback on feeling states and subsequent actions. Beliefs (i.e., justifications in the current framework) such as, “I will likely fail at this” or “She will never like me” activate feelings of failure and defeat and tend to lead to behavioral avoidance and contribute to maladaptive cycles.

The focus of traditional cognitive therapy is to develop awareness of one’s justification system and to determine the validity and adaptiveness of various beliefs. For example, it is common in Beckian cognitive therapy to teach patients to conceive of their verbal cognitive system as consisting of three levels: (a) automatic thoughts, (b) intermediate reasoning, and (c) core beliefs. Patients are then taught to link the content of their beliefs at those levels to feelings and actions, and then to develop systematic ways to determine which justifications are accurate and helpful and which are not.

It is worth noting that there has been a shift in the past two decades toward “third wave” cognitive– behavioral therapies (e.g., ACT; DBT). These approaches tend to take a slightly different approach to relating to one’s thoughts. Rather than attempting a systematic analysis of whether or not one is making adaptive or maladaptive interpretations as traditional cognitive approaches tended to do, third wave approaches emphasize the need to be aware of and accept one’s thoughts and feelings regardless of their content. The emphasis is less on trying to develop an adaptive control of one’s justification system, as being able to observe and accept one’s stream of conscious thought and not engage in experiential avoidance (defensiveness of unwanted feelings or images). With their emphasis on awareness and acceptance, third wave approaches thus tend to have more conceptual space for the experiential and defensive systems.

Conclusion

In looking over the five systems of CAST and lining them up with the major paradigms of individual psychotherapy, ask the simple question: Is the alignment difficult to see? If not, then a major conclusion about the field of psychotherapy can be reached. What appear as paradigms in the field are really a function of focusing on different systems of psychological adaptation.

If you or someone you know is in a training program that requires you to focus on a particular orientation, the following questions should be raised: Isn’t it the case that habits and lifestyles, emotions and emotional functioning, relationships and attachments, coping and defenses, and cognitive interpretations and self-concepts are all important to understanding psychological adaptation, disorders and change? If so, then why would someone have to choose to only focus on one or two of these domains, and identify with a “tribe” that is defined against tribes that focus on other domains? Isn’t this like a cardiologist who proclaims the key to overall biological health is a good circulatory system, the other systems be damned?

Developments in theory, training and practice are being made such that psychology and psychotherapy no longer need to be organized as horse races between them. Instead, we can now start to transcend the paradigms and operate from a coherent and comprehensive understanding of human psychology. Surely, if we are able to "see the whole elephant" the field will be better off in the end--and so will our patients.