Suicide

Pervasive Adult Developmental Disorder

A new way to look at folks with serious difficulties.

Posted August 24, 2015

In the four years I worked at the University of Pennsylvania (1999-2003), I directed a randomized controlled clinical trial assessing the effectiveness of a brief cognitive therapy intervention for folks who had recently made a suicide attempt. I was looking through those slides the other day and was reminded of a construct that I had started to develop, but for a host of reasons I never shared in the literature. I think it is a construct worthy of some reflection, so I will detail it here. The concept was Pervasive Adult Developmental Disorder. I developed it because I was dissatisfied with the way the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual System worked for categorizing the problems these folks presented with. Instead of implicitly reducing their problems to mental diseases inside the individual, I felt we needed a way to characterize their lives as being developmentally injured and off course, and to capture the many systematic influences that contribute to this situation.

If you have not worked folks who are severely impaired who live in severely limited and harsh environments, it might be hard to imagine the kinds of difficulties that these individuals encounter. I will describe two such cases to give you a flavor. I saw Helen, a 28 year old Caucasian female, shortly after she overdosed on a mix of heroin, alcohol, and prescription medications she had obtained. Her medical file revealed she had over ten documented suicide attempts and she would tell me that she had seriously attempted suicide on thirty or more occasions. Helen was adopted and described her parents as neglectful and oblivious. When she was 10, she was befriended by a man who turned out to be a psychopath, and he proceeded to torture and abuse her for years. He managed this by first hooking her into heroin prior to starting the abuse. Her addiction and the fact that he sometimes showed a deeply caring side, meant that she would return to him repeatedly, only to be physically and sexually victimized. Ultimately, Helen was freed from this relationship when he was killed in an altercation. But her heroin addiction did not die with him, and she ended up dropping out of school and living on the streets. When I encountered her, she lived under a bridge and performed fellatio on homeless men in return for heroin fixes. Not only did she meet criteria for Major Depression, Poly Substance Dependence, and Borderline Personality Disorder, she also had such severe symptoms of dissociation that she met criteria for Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Or consider Pamela, a 45 year old African American woman I also treated. Like Helen, Pamela also had a sexual trauma history, having been molested by her father from ages 12 to 16 (he was a minister). Unlike Helen, though, for a portion of her life Pamela had been able to achieve some stability. She got married at 20, and had three children. However, she never really loved her husband; he was safe, but not someone she really felt attracted to. When she was in her mid 30s, she met someone who excited her. He was a substance user and soon Pamela found herself having an affair and engaged in heavy cocaine use. When she sold the family car for a fix, her husband divorced her and took custody of their children. Pamela lost her job and her contact with her kids for five years. She finally got clean from substance use, but had no money and no job and lived in an abandoned building. Cold, hungry and alone, she came into our study after she tried to kill herself via an overdose. She met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder with Psychotic Features (she heard voices telling herself to kill herself), Substance Dependence in Partial Remission and PTSD (she still had nightmares and flashbacks).

These are just two examples of the kind of cases we saw. As I hope these vignettes portray, a purely disease model of mental illness does not capture well at all the kind of systemic problems that were involved in these cases. Of course, maladaptive behaviors and even genuine mental disease states were often a part of the presentation. But really what we were looking at was a failing developmental trajectory that was caused by many factors, including a harsh, competitive ecology; institutional barriers based on race and class; histories of abuse, alienation, and mistrust; impulsivity, aggression and poor insight; substance misuse; and limited to very limited material and/or personal resources to manage the enormous problems in living.

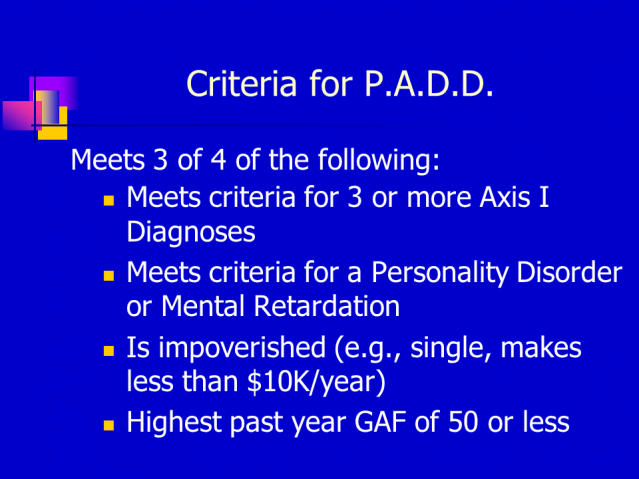

It was for all these reasons that I started thinking about characterizing the folks we saw as having Pervasive Adult Developmental Disorder. The definition of PADD was a troubled developmental trajectory involving serious symptoms of mental distress and dysfunction, low environmental resources, low personal resources, and enormous hurdles which prevent individuals from achieving a basic, safe, stable standard of living. I developed it because the current labels DSM did not capture this complex picture. Interestingly, I operationalized P.A.D.D. based off of the old DSM-IV axis system, depicted below (unfortunately, the new DSM V did away with the old axis system).

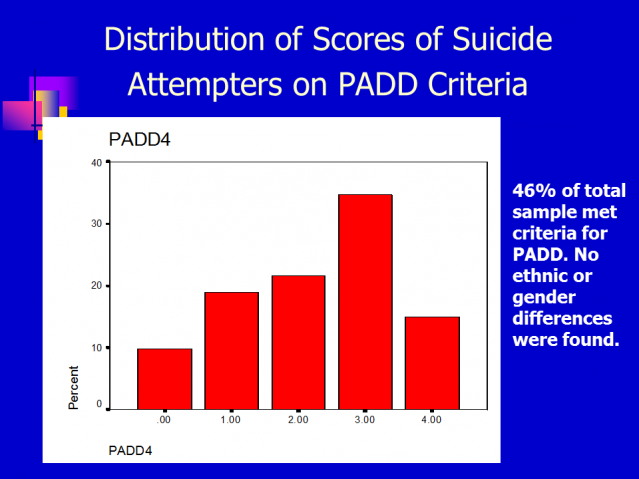

This graph breaks down the frequencies of PADD criteria met by folks in our study:

As depicted, 46% of the sample of 180 folks we brought into the study met criteria for PADD. That is, they had three or four of the above criteria (3 or more axis I disorders; an Axis 2 disorder; were impoverished; had a highest past year Global Assessment of Functioning of below 50). This fact alone points to why we need a reconceptualization of categories of psychological/psychiatric disorder, especially for those who are “low functioning” across many domains.

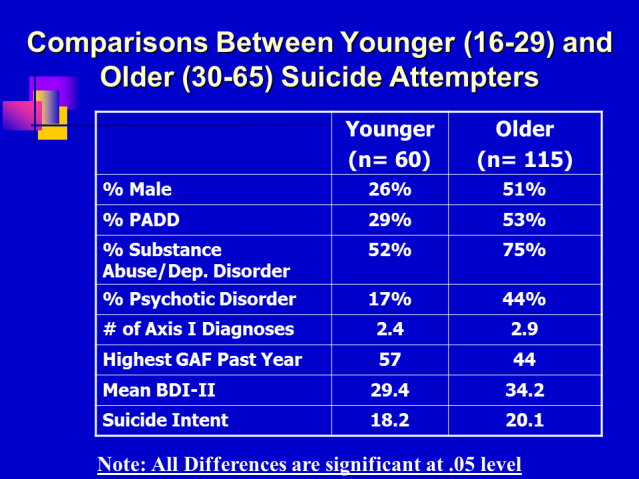

Consistent with the idea that there is a developmental trajectory at work, we conducted a cohort comparison, and found that the younger folks in our study had notably less pathology than the older folks.

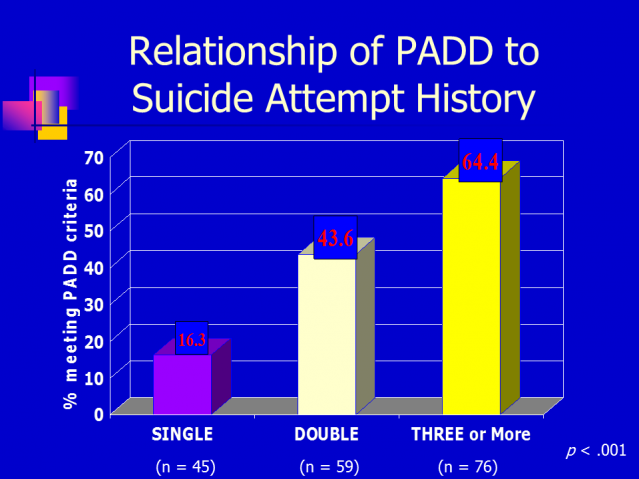

And consistent with markers of suicide risk, the PADD criteria were clearly associated both with past suicidal behavior as shown here (64% of the folks who had three or more previous suicide attempts met PADD criteria compared with only 16% of folks for whom the current attempt was the first).

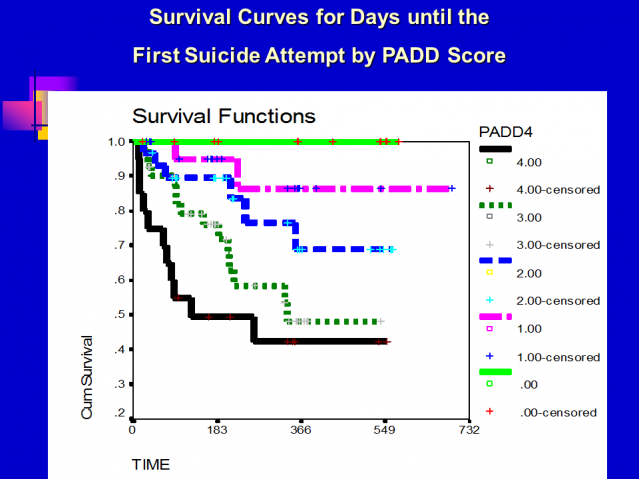

And, in terms of predicting subsequent suicidal behavior, the criteria of PADD were also very predictive. The graph below is called a survival graph and it represents the time until someone in the study made a repeat suicide attempt. This graph shows that none of the 18 individuals that did not meet any PADD criteria made a subsequent suicide attempt, but 10% of the 35 individuals who met one criterion did, whereas 30% of the 37 individuals who met two did, 50% of the 55 individuals who met three or more and 60% of the 32 individuals who met all four criteria made a subsequent suicide attempt in the year following the index attempt.

When I presented this concept at conferences, my general experiences were that folks who worked with these populations appreciated the new angle. Some worried that it sounded pejorative. Others pointed out that by including poverty with mental illness symptoms, I was making problematic linkages. My reply was that poverty is a major component of stress and functioning, and the combination of poverty (i.e., low resource) and mental distress and dysfunction is brutal. I welcome additional feedback on this concept and encourage folks working with this kind of population to consider developing alternatives to the DSM categorization system.