Psychoanalysis

The Artist at the Fragile Estate

Looking at Mark Rothko’s artworks through the lens of psychoanalysis.

Posted August 14, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Mark Rothko’s artwork can be understood through psychoanalysis.

- Viewing Rothko’s work can help people find therapeutic solace.

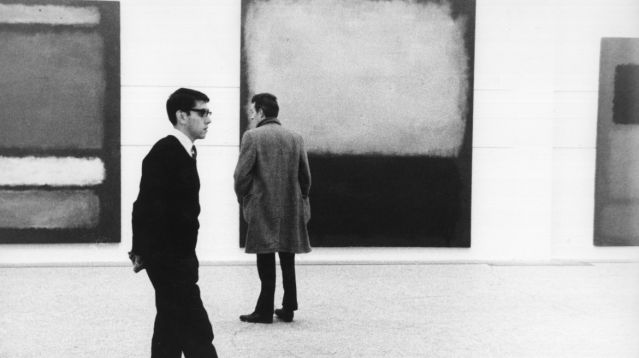

Mark Rothko’s work (1903 - 1970), it is sometimes proposed, has a therapeutic effect on its viewers. From my own experience, I can confirm this uncanny metaphysical pull of Rothko. Whenever I struggle in life, I feel drawn and connected to Rothko’s paintings. But why?

Rothko: Between Modernism and Postmodernism

Some have argued that Rothko’s work is an expression of postmodern culture, identified by cultural relativity, aesthetic confusion, and the breakdown of ethical rules. There is no objective truth in postmodernism, nothing stable, no overarching narrative for us to hold on to.

Rothko himself noticed the postmodern ethos of his work: “Truth,” it is said, “must strip itself of self”—a typical postmodern expression. However, he adds, “Truth must strip itself of self, which can be very deceptive.”

Rather than embodying the postmodern ethos completely and uncritically, I assume Rothko’s comments about “Truth” are a critique of the moral supremacy of abstract expressionism.

Rothko, not a postmodern, wasn’t a modernist either—too pretentious, too proto-fascist, oblivious of the sublime he regarded the clean lines of Mondrian or Corbusier, argues the art critic Clement Greenberg in his essay “Modernist Painting” (1960).

Rothko recognized and rejected the tyrannical function of modernist ideology embodied in and sustaining the Cold War cultural feuds between capitalism and communism.

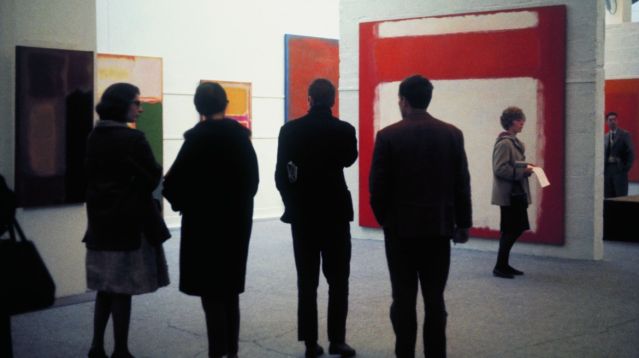

Rothko’s Seagram Paintings, a series on display at the Tate Modern in London, speak of his suspicion towards both modernist high grounds and the postmodern situation. The series of paintings were commissioned to be displayed in an elitist Manhattan hotel, but Rothko never submitted them to the contractor. He felt disgraced by the juxtaposition of his “spiritual work” and the bleak consumer culture of New York elitism—his visceral reaction to postmodernism. Instead, he gave his metaphysically charged paintings to the Tate in London for public display. A political act? A rebellion against consumer culture? A manifestation of his artistic vision? Maybe both?

Healing Power

Rothko’s paintings, specifically his late works, are often described as possessing a healing power on the viewer. From a Jungian view, this might be because of their position between the predictability of modernist expressionism and the psychic chaos of surrealism. In Rothko’s days, surrealist practices were generally despised because of their grounds in the (by definition, inexplicable) unconsciousness.

The American consumer’s inner life, contrasting with the Freudian architecture of the mind, wasn’t meant to have a chaotic subconscious in constant need of exploration, perhaps even scratching on the psychotic. Rather than a complex psychic subscript, American consumerism demanded the easily accessible categorical imperatives of capitalism to govern our inner lives.

Rothko was inclined to scratch the psychotic—yet, only scratch, never to disappear completely. The color blocks of his Seagram Murals radiate, hover, transcend, and move, but in the end, they are still composed of rectangles and squares. “Shapes cannot be firmly bound, easily located, or securely identified,” says Rothko’s biographer James Breslin.

In the ’40s, Rothko read the psychoanalytic texts of Carl Jung. Translating Jungian analysis work into his paintings, Rothko’s self-ascribed goal was to deploy art as a medium to clarify and unify discordant Jungian archetypes within the viewer’s psyche—and the artist’s own. In Rothko’s own words, he wanted to make his audience “cry” before the sublime.

Rothko’s artistic work had a self-therapeutic effect, too. In Jung’s texts, we find suggestions for the treatment of schizophrenia in the form of self-exploration through painting. The psychotic artist would have translated into art the archetypical elements of childhood experience and personal inner conflicts. The result, the painting, is meant to raise the inner experience to the level of a “historical myth.” According to Jung, our inner and outer lives are structured along those myths. And by making the myth experiential, the painter and audience enter a therapeutic dialogue with themselves.

James Breslin described the therapeutic potential of Rothko’s work:

“His new paintings created a breathing space. Yet these paintings do not seek simply to ‘transcend’ the walls of an unalterable external reality by soaring upward into either an untrammelled freedom or a vaporous mysticism. Rather, by (in Rothko’s words) pulverising the verge of dissolution—his works free us from the weight, solidity, and definition of a material existence, whose constricting pressures we still feel. Rothko combines freedom and constraint and if these paintings create ‘dramas’ with the shapes as the ‘performers’ they stage a struggle to be free.” (p. 168).

Freedom, Therapy, and Art

Rothko associated this quest for freedom with the Abraham of the Old Testament. The road to freedom, inner and outer, always scratches the dissolution of clear boundaries. Rothko was drawn to the psychotic loss of reality because, on its boundaries, we find the possibility of freedom. Between structure and chaos, in the language of Jungian archetypes, we find the sublime road toward freedom.

In Freudian terms, Rothko’s idea of freedom expresses the near loss of reality where the Ego gives in to the Id, almost tearing it away from the external world and into itself.

Viewing Rothko’s work, we too can experience this fragile estate and find therapeutic solace in not completely “loosing it” and not being completely “square” either.

References

Greenberg, C. (1960). Modernist Painting in The Collected Essays and Criticism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Breslin, J. (1993). Mark Rothko. A Biography. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.