“Is this the right mental health app for me?”

I was first asked this question as a doctoral student years ago and didn't think much of it.

“Sure,” I said to my client, “It seems fine to me. As long as you are finding value from it—it can’t hurt!”

Fast forward a few years, and this question has become commonplace for the clients I work with, especially among those most vulnerable—adolescents and young adults. In fact, I now make it a point to ask all of my clients if they are using any sort of mental health app to learn about their struggles or manage their symptoms. Well over half say that they do, and I’d put money on the fact that this holds true across most of the care spectrum.

The truth is that mental health apps are here to stay. Experts estimate there are more than 10,000 mental health apps that currently exist in the app store, and more than a few are bound to end up in the hands of your caseload. Although my past self was relaxed about this truth, my present self has a newfound sense of urgency about thinking critically when responding to this question.

Why?

Because we are the gatekeepers between our clients and the information they obtain about their health.

Although the vast majority of mental health apps currently on the market are likely well-intentioned, very few actually have empirical data supporting their content. Strategic marketing ploys found on many app description pages and websites often highlight the evidence-based nature of the overarching theory behind the platform, or that the services within the app were “pulled from” evidence-based treatment, despite having no evidence base of their own. Moreover, many app developers may not even have a mental health professional on their team, relying solely on ambitious product developers who pull close enough content from a variety of professional sources.

To be fair, many of the major mental health apps out there are not contra-indicated nor going to cause anyone significant harm. But it doesn’t take too long to come across some truly cringe-worthy apps that are not too far down the list on the app store.

We might instinctively know to stay away, but our clients usually don't have this same intuition. As such, it’s our job as mental health professionals to bring a healthy sense of skepticism to these platforms and adopt a framework for evaluating the legitimacy of the multitude of apps our clients are using on a daily basis.

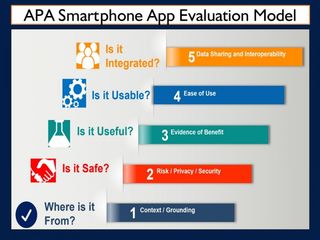

Luckily, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recently published what they call their App Evaluation Model. This model was developed to empower clinicians with a five-step framework for evaluating the validity and safety of all the mental health apps out on the market.

The APA acknowledges that while any and all recommendations around mental health apps is a personal decision between you and your patients with rarely a simple "yes" or "no" answer, there is a step-wise framework that can be followed to ensure all important information is considered when evaluating the legitimacy of a mental health app.

This framework is as follows:

Step 1: Gather background information

Before any other evaluation can take place, you must gather background information about the app. This includes information about the developer, cost, advertising, development process, and general content. This type of information can often be found by visiting the app’s website or reading the details of the app in the description within the app store.

The purpose of this step is simply to get a better understanding of the context around the app in question. For example, you may want to avoid apps that have not been updated in over a year or that appear to endorse content or recommendations that go against your own clinical approach or understanding of the client. In essence, this step is about getting a feel for the app in question, so don't be afraid to lean into your clinical intuition.

Step 2: Risk associated with privacy and security

Data privacy and security is one of the largest challenges that face us today, and patient health information (PHI) is no exception. While risk is a broad construct in the clinical sense, each app must be evaluated on how much risk it carries with respect to privacy and security.

Does the app ask for personal information? Does the developer sell client data to third parties? Is the app HIPAA-compliant? Questions such as these should all be considered, and apps that contain more privacy and security risks (e.g., apps that administer clinical assessments or ask for specific health information) should be subject to greater scrutiny. Privacy and security information should all be found in the app’s privacy policy. For apps that do not have a privacy policy, it’s best to avoid recommending it.

Step 3: Evidence

Your task at this step is to evaluate the presence of any evidence supporting the app’s claims. Don’t be fooled by non-specific language about app content being “based on” or “informed by” evidence-based practices. What you really want to know is if the app, in and of itself, has been subject to empirical research.

For the most part, this is a rare phenomenon. For apps that do not have their own evidence base, the APA recommends that you download the app yourself to examine how closely the structure, content, and practices within the app actually adhere to evidence-based practice. If the app presents any information that you would not personally endorse, it might not be the best app to recommend to your clients.

Step 4: Ease of use

For apps that have made it this far in the evaluation process, ease of use is your next consideration. This is a particularly important step because long-term engagement in mental health apps is notoriously poor. Time and time again, user research in the context of mental health apps has shown that individuals tend to get intrigued by a new app, use it for a few days or weeks, and never touch it again.

Apps that promote long-term use through user-friendly features are the best bet for your caseload. Although there is no formal way to evaluate the ease of use, simply download the app and ask yourself—is this something I could see myself doing day-after-day or week-after-week? If the answer is no, chances are, your clients will feel the same way.

Step 5: Interoperability

The final step in the evaluation process is determining whether or not the app in question can inform some part of your care or integrate into your treatment approach. For example, collaboratively reviewing data from apps that collect daily information about mood and activities is a wonderful method for helping clients better communicate their lived experiences throughout the week.

Similarly, some apps can integrate into EHR systems for increased data visibility, or can provide summary reports to inform treatment decisions and assist in practicing measurement-based care. In this way, apps that promote interoperability and encourage collaboration should always be recommended over those that do not.

Importantly, the APA acknowledges that each subsequent step in the framework represents a lower priority with regard to evaluating apps. For example, apps that do not pass privacy and security screening (step 2) should not continue on to later stages of inquiry, whereas apps that do not promote interoperability (step 5) may still be perfectly fine in the right context. Either way, clinical judgment is needed to determine if and when an app should be recommended in your practice.

If nothing else, my own experience throughout the years has taught me that communication is key. We need to have open and honest conversations with our clients about their use of mental health apps and how they might be used to supplement our work. Only then can we leverage technology to elevate our practice. My hope is that this framework empowers you all to have such conversations.