Gender

New Research Shows How Gender Expectations Drive Our Politics

Attitudes about gender influence our political preference.

Posted July 22, 2022 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Regardless of whether one is a man or a woman, favorable attitudes towards masculinity are more associated with conservatism.

- Conversely, favorable attitudes towards femininity are more associated with progressivism, regardless of one's gender.

- Steven Pinker's data show that the world's movement towards greater feminization in the past 2,000 years has led to great reductions in violence.

The recent Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade has sent political commentators into a frenzy trying to predict how this will reshape American politics. The original Roe v. Wade decision (and the more recent Dobbs v. Jackson decision, overturning Roe v. Wade) concerns many aspects of American life, including the extent to which the government can dictate what a person does with his or her own body, and also whether these decisions, especially regarding abortion, are best left to state governments or to the federal government.

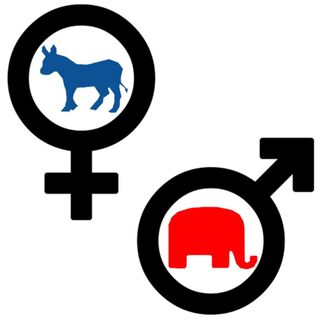

More broadly, however, the overturn of Roe v. Wade primarily involves the intersection of gender and politics. For decades, political commentators like David Brooks and Jude Wanniski have said America has a "mommy party" (the Democratic Party) and a "daddy party" (the Republican Party), and though the reduction of people's political beliefs to feelings about their mother and father might seem an oversimplification, recent research findings validate this perspective.

Earlier this week, New York Times columnist Thomas Edsall presented these findings, including original research by political scientist Monika McDermott and additional research summarized by Nicholas Winter from the book Community Wealth Building and the Reconstruction of American Democracy.

According to McDermott's findings (2016), regardless of whether one is a man or woman, “the more ‘masculine’ an individual is, the more likely he or she is to affiliate with the G.O.P. and vote for Republican candidates... and the more ‘feminine’ traits a person possesses, the more likely that person is to affiliate with" the Democratic Party. Furthermore, according to McDermott, “once gendered personalities are accounted for, the long-standing sex gap in partisan preferences disappears.” Hence, it's not gender itself, as once believed, but rather one's attitudes towards masculinity and femininity that best predict their political leanings.

But what is meant by "masculinity" and "femininity?" McDermott (2016) equates "femininity" with being "understanding, sympathetic, warm...compassionate, gentle...affectionate, sensitive to [the] needs of others, and tender;” and she equates “masculinity" with being “willing to take risks, forceful, [having a] strong personality, assertive, independent...aggressive, dominant, [and] willing to take a stand.”

Nicholas Winter's assessment (Edsall, 2022b) takes things a step further, noting “that people (men or women) who support traditional gender roles tend to favor the Republican Party and people who either reject or at least do not valorize traditional gender roles (men and women both) favor the Democratic Party.”

In an article on a similar topic in March, Edsall (2022a) highlighted the findings of political scientists Melissa Deckman and Erin Cassese which echo those offered by McDermott and Winter. Deckman and Cassese reported that a considerable majority of Republican women (57 percent) in 2016 believed "the United States has grown too soft and feminine," while only a small minority of Democratic women held this belief. Similarly, Republican men were also much more likely than Democratic men to believe that the country had become "too soft and feminine." Supplementing these findings are those of Bradley DiMariano, who found that both Republican men and women have considerably more favorable attitudes towards authoritarianism—being led by a "strongman"—than their respective Democratic counterparts.

In a previous post on gender and politics, I speculated on the causes of the phenomenon described above. My personal and professional experiences lead me to believe that the differing socialization processes that boys and girls endure shape our values as adults. For thousands of years, traditionally masculine environments have socialized children (mostly boys, but also some girls) in ways meant to prepare them for the burdens that typically fall to men: hunting, warfare, and hard physical labor. Traditionally feminine environments have socialized children (mostly girls, but also some boys) in ways meant to prepare them for the burdens that have typically fallen to women: child-rearing and domestic tasks.

Regardless of whether one is a boy or a girl, if an individual feels that the traits they naturally embody are a good match for the environment they've been socialized in, they will likely adopt the rules, expectations, and norms (RENs) of that environment and ardently defend them. But if the traits they naturally embody are a bad match for their environments, they will likely reject the RENs of that environment with great fervor.

In my clinical work with adolescents, I can attest to the fact that there is nothing more uncomfortable than being an effeminate individual (boy or girl) in a strong masculine environment or a masculine individual (boy or girl) in an overtly feminine environment, though the consequences are very different.

Effeminate boys in strong masculine environments are often physically intimidated, hazed, and called gay slurs, while effeminate girls in these masculine environments are often exploited sexually. As for masculine girls in feminine environments, while they are not usually intimidated physically, they are often cyberbullied or ostracized for various reasons due to their lack of femininity. Masculine boys in feminine environments are often disciplined excessively for being overly "aggressive" or have their "male privilege" regularly called out for behaviors that would go unnoticed in a masculine environment.

Is it not obvious how these adolescent experiences can lead to strong political leanings later in life?

It is imperative that we understand how attitudes about gender influence politics because, as Steven Pinker reminds us in his paradigm-shifting book, The Better Angels of Our Nature (2012), the world has been moving, albeit slowly, towards greater femininity for at least the past 2,000 years. Though there are some who rail against this push towards feminization (or in their words, "wussification"), I am with Pinker in celebrating this development.

The feminization of our species—through processes that Pinker calls "pacification," "civilizing," "the humanitarian revolution" and "the rights revolutions"—has led to dramatic decreases in murder, combat-related deaths, torture, slavery, rape, physical and sexual abuse, demographic-based discrimination and many other of our worst human impulses in the past two millennia.

Though these declines haven't always been linear or without periods of temporary regression, they offer hope in what can often seem like an ocean of hopelessness. They also offer a blueprint for the direction of our species, with which we can build a civilization that most effectively balances masculinity and femininity (regardless of the sex or gender of the person embodying these traits) for the most peaceful and prosperous future possible.

References

Edsall, T.B. (2022a). The Gender Gap Obscures More About Politics Than It Reveals. The New York Times, July 20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/20/opinion/gender-gap-partisanship-poli…

Edsall, T.B. (2022b). What We Know About the Women Who Vote for Republicans and the Men Who Do Not, The New York Times, March 30, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/30/opinion/gender-gap-republicans-democ…

Winter, N. (2020). “Gendered (and racialized) partisan polarization,” In M.C. Barnes, C.D.B. Walker, & T. M. Williamson's (Eds.) Community Wealth Building and the Reconstruction of American Democracy: Can We Make American Democracy Work? ISBN: 978 1 83910 812 9 Extent: 296 pp

McDermott, M.L. (2016). Masculinity, Femininity, and American Political Behavior. Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN-13: 9780190462802; DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190462802.001.0001

Deckman, M.M. & Cassese, E. C. (2019). Gendered Nationalism and the 2016 US Presidential Election: How Party, Class, and Beliefs about Masculinity Shaped Voting Behavior, Politics and Gender 17(2):1-24.

Pinker, S. (2012). The Better Angels of Our Nature, Penguin, Cambridge.