Depression

Four Types of Depression

On situational, biological, psychological, and existential depression.

Posted April 27, 2020 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Virtually everyone has some experience with depression; however, the term “depression” has so many different meanings that confusion and invalidation often result when laypersons talk about their experiences.

In the most poignant discussion on depression I've ever heard, writer Andrew Solomon said this, in his now-famous Ted Talk:

"It's a strange poverty of the English language... that we use the same word, 'depression,' to describe how a kid feels when it rains on his birthday and to describe how somebody feels the minute before they commit suicide."

To address this problem, I have created a simple schema, based on my work with patients and my own personal experiences, to help people understand each other better when talking about 'depression.'

In this article, I describe four different types of depression: situational, biological, psychological, and existential. While this schema does not represent a formal diagnostic model, I believe it can be helpful, especially for laypersons, to better communicate what they're experiencing so they can get the help and validation they most need.

Type 1: Situational Depression

Are you feeling isolated and depressed from the COVID-19 quarantines? Have you ever cried for a week and struggled to get out of bed after a breakup? Did you ever have brief thoughts of suicide after getting rejected from a college you applied to?

If you’ve ever experienced intense sadness in response to these or similar events, congratulations: You are a warm-blooded human being. You’ve also experienced what I call situational depression.

As humans, it is completely normal to feel sadness, even for extended periods, in response to negative events and isolating situations. There aren’t many people who, upon losing their jobs or a loved one, are able to feel unperturbed. In fact, not only do I believe there is nothing wrong with experiencing situational depression, it is probably abnormal to not feel depressed in such cases. However, when these feelings stick around for more than a few weeks, or when thoughts of suicide persist, it is a sign that one's depression is better explained by one of the other types below.

In my experience, situational depression is nearly universal within the human condition, which means that if this is something you are currently experiencing, you have company—and a lot of potential support. Unfortunately, however, since this type of depression is so common, many people consider themselves experts on the subject and feel emboldened to give unsolicited advice to anyone they hear is struggling with “depression.”

Much of the time, the well-intended advice provided by those who have only experienced situational depression is not only vague and unhelpful but sometimes it can actually make a person feel more depressed. Friends and family members may say: “Stop feeling sorry for yourself and move on.” Or “So many people have it much worse than you!” This only makes individuals with more severe forms of depression feel worse, not better. In lieu of statements like these, depressed individuals often prefer that a loved one follows the advice from the 12-step tradition: "Don't just do something; sit there."

Type 2: Biological Depression

With biological depression, an individual’s depressive symptoms start with an imbalance in any of the neurotransmitters (like serotonin and norepinephrine) or hormones (like estrogen, progesterone, and thyroxine) that affect our mood and physiology.

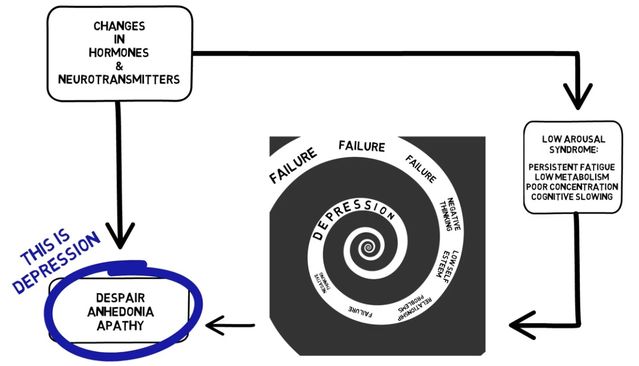

In some cases, changes in neurotransmitters and hormones can lead directly to feelings of despair and anhedonia. In other cases, biomedical conditions like hypothyroidism, Epstein-Barr, or even sleep apnea can cause a major disruption of energy levels, creating a syndrome of low arousal marked by persistent fatigue, low metabolism, poor concentration, and cognitive slowing (Gold et al., 1981; Longo et al., 2011). It is this low arousal state that mediates the indirect path to depression by preventing individuals from achieving their life goals, making depression a common outcome.

This syndrome of low arousal, which may be caused by numerous factors, including reduced brain metabolism (Gua et al., 2021), is itself, not depression: it simply makes the activities of daily living (ADLs) and the achievement of one's goals much more difficult. However, as failures begin to mount, negative thinking patterns and low self-esteem often follow, making depression an indirect consequence of these biochemical changes.

In either case, when biological factors start generating depressive symptoms, a vicious cycle ensues. At this point, something is needed to break the cycle, and this is where medication can be the most helpful—whether it be a traditional antidepressant or treatment for a specific medical condition, like hypothyroidism. As I tell my patients, medication alone will not solve your problems, but it can produce a biological state (usually marked by increased energy and concentration) that will enhance your ability to implement the plans discussed in psychotherapy.

Type 3: Psychological Depression

The third type of depression is called psychological depression, because it is linked to psychological factors, like losing perspective, unrealistic expectations, and negative self-talk.

For most of us, having our hopes and dreams continually crushed by reality is among the worst experiences we can endure. For some, the primary means of coping with this is to deprive themselves of future hopes and dreams, so they are never disappointed again, and this adaptation can work so well that people use it indiscriminately to protect themselves. However, when people overuse this defense mechanism, apathy and hopelessness can result. In my experience, I have found that psychological depression responds equally well to both cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy, though each approach would address the problem in different ways.

Aside from losing perspective, setting unrealistic expectations, and overusing defense mechanisms, psychological depression can also be a consequence of a dysfunctional romantic relationship. In some cases, separation anxiety keeps people together even after it becomes clear they want different things out of life. In more extreme cases, co-dependencies and abusive dynamics can pose serious threats to one's physical and emotional well-being. Here, a skilled therapist is needed to determine whether the relationship can be saved or if separation is necessary to alleviate the depressive symptoms of the afflicted person.

Type 4: Existential Depression

While the trigger for situational depression is usually a negative event (e.g., the loss of job), the trigger for existential depression is often, ironically, a positive event: usually, one that someone has been looking forward to for a long time.

How can a positive event trigger a depressive episode? For many of us, we decide in adolescence to dedicate ourselves to a particular goal that we believe will give our lives meaning and provide us with self-actualization. The goals to which we aspire may include lofty career achievements, like becoming a doctor, specific personal desires, like having a child or, possibly, a trip to a fantasized destination.

Regardless of the goal, when we organize our lives around its attainment, we often create an unrealistic expectation that this will yield an unending state of bliss. In some cases, the attainment of these goals does give us the satisfaction we crave, but many times it doesn’t. To spend your entire life pursuing a single goal and then realize that it didn’t bring the joy and meaning that you expected is enough to send most people into an existential crisis.

“Was my entire life a waste of time?” “If achieving this goal didn’t give my life meaning, will it ever have meaning?” “Where do I go from here?” These are the questions asked by someone I would describe as having existential depression, and this type of depression often causes a person to question everything they once believed to be true. Without the meaning they hoped to achieve after the attainment of their goal, the things in life people once enjoyed no longer give them pleasure, and they feel lost without a goal to pursue in the future.

In addition to the disappointment following a positive event that did not bring the joy one expected, existential depression is also likely to result from difficult life circumstances that are likely to become permanent. In cases where one is diagnosed with a terminal illness or experiences a debilitating injury, an individual's entire existence is vulnerable to loss and radical change. Here, existential depression also very common.

Existential depression can be the trickiest to address: Taking Prozac won’t give those afflicted a new identity or purpose, nor will it help them to discover the meaning of life. Similarly, psychotherapy approaches that focus solely on concrete symptom relief are not very effective either. The symptoms emanating from existential depression come from a deep, nebulous source and don’t respond much to techniques that simply address one’s cognitive errors, irrational thoughts, or lack of engagement in pleasurable activities.

In my experience, existential depression generally requires a combination of strategies, integrated over a long period of time. First, I believe that ongoing psychotherapy with a therapist who is insight-oriented (possibly from a psychodynamic/psychoanalytic orientation) is a good place to start. Therapy should not be pushed at a pace faster than what the patient is willing to go, and it may seem that progress is not being made, even after a couple of years in therapy. However, this type of therapy will provide patients with the safe space necessary to explore new possibilities and identities in an environment that is validating and free of judgment and expectations.

Second, exploration and participation in groups oriented towards big-picture goals (e.g., religious/spiritual groups, philosophy circles, book clubs, humanitarian organizations, etc.) can be an important adjunct to therapy, helping patients consider different life goals and purposes. Third, I think that experiencing foreign cultures and different ways of life—as Elizabeth Gilbert described in Eat, Pray, Love—can be especially helpful as well.

(For more on existential depression, check out my article here)

---------

In conclusion, in most cases, people don’t simply suffer from just one of the depression types described above, but a combination. Once again, a well-trained therapist can be of great assistance in helping people discern which combination of depression types they suffer from, and in devising a treatment plan according to each person's assets, limitations, and personality type.

If you are experiencing one of the types of depression described above, you might feel empowered to pursue treatment with a well-trained therapist. I hope this post is enough to convince you that no two people experience depression in the same way, and thus, we should all be careful when assuming that our own experiences with depression automatically apply to everyone we meet who uses the word "depressed" to describe themselves.

-----

To see a video of this article, click on this link or the link in the box below.

References

Gold, M.S., Pottash, A. L. C., & Extein, I. (1981). Hypothyroidism and Depression Evidence From Complete Thyroid Function Evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association, 245(19):1919-1922.

Longo D.L., Fauci A.S., Kasper D.L., Hauser S.L., Jameson J.L., Loscalzo J. (2011). Disorders of the thyroid gland. In Harrison (Ed.), Principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Gua, X., Keab, K., Wanga, Q., Zhuanga, T., Xia, C., Xu, Y., Yang, L., & Zhoua, M., (2021). Energy metabolism in major depressive disorder: Recent advances from omics technologies and imaging. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 141.