Parenting

Parenting Adolescents and Managing More Emotional Intensity

Normal separation, disagreement, and experimentation all intensify emotions.

Posted September 27, 2021 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Key points

- Adolescent detachment for independence and differentiation for individuality can increase emotional intensity between parent and teenager.

- Healthy emotionality helps parents and adolescents stay sensitively informed about significant happenings in their inner and outer experience.

- While tempting to do, it's best that parents and teenagers do not use the expression of strong emotion manipulatively to get their way.

The onset of adolescence often arouses more emotion because it begins with loss.

For parents, gone is the adoring and adorable little girl or boy; for the teenager, gone are the idealized and all-knowing parents. Childhood, that magical period of mutual entrancement, is over.

In its place (around ages 9-13) begins the equally marvelous, but more difficult to parent, 10- to 12-year coming-of-age passage that transforms a little girl into a young woman, and a little boy into a young man. “Adolescence,” we call it.

Compared with childhood closeness, now growing changes can stress the parent/daughter or parent/son relationship. Now there is more distance and disagreement as teenage detachment for independence and differentiation for individuality begin to grow them apart, which is what adolescence is meant to do.

In consequence, parent and teenager can find each other more emotionally intense with each other, particularly during normal disagreements that increasingly occur. For example, the adolescent can get more intense (frustrated and angry) when not getting the freedom she or he wants, while the parents can get more intense (worried and anxious) over growing risks, not knowing for sure what is best to decide.

So consider the challenge of managing more emotional intensity.

Appreciating emotion

Start by recognizing the importance of emotion in human functioning. From my perspective, emotions are part of everyone’s affective awareness system that helps them feel when something significant is happening in their internal or external world of experience that deserves attending to.

Each kind of emotional awareness focuses on a different aspect of life experience. For example, on the hard side fear warns of danger, anger responds to violation, and frustration identifies blockage. On the happier side, love affirms devotion, joy celebrates fulfillment, and curiosity expresses interest.

Without access to their emotion, people lack important self-awareness: “I don’t know how I feel! I don’t know what’s going on with me!” Our emotions help keep us in touch with ourselves.

However, while emotions can be very good informants, they can be very bad advisors.

“Thinking” with one’s feelings can get people into all kinds of difficulty. Yielding to infatuation can lead a young person into accepting dangerous attention. Retaliating in anger can make a bad situation worse. Avoiding a scary challenge can limit opportunities for growth.

So, between parent and adolescent, it’s important to honor the message emotion brings when, for example, feeling disappointed by the other person’s response. In this case, rather than follow emotion’s unhappy advice and charge, “You’re never there for me,” it can better serve the relationship by relying on judgment to respond: “I’d like to talk about what I was expecting from you.”

The safe management of strong emotions requires the discipline of self-restraint.

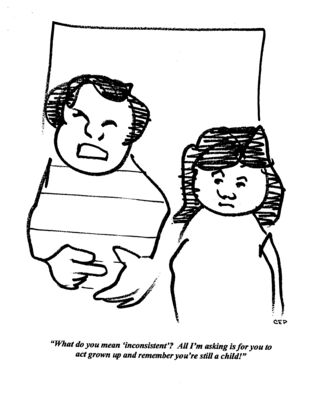

Emotional extortion

Sometimes, it can be tempting for a parent or teenager in disagreement to use the expression of strong emotion to gain influence, offering the cessation of hard feelings, for example, in exchange for some concession from the other person.

Many are the emotionally manipulative ways. Here are a common few.

- Sulking: “To restore my spirits, give me my way.”

- Suffering: “To heal my pain, give me my way.”

- Anger: “To ease my madness, give me my way.”

- Rejection: “To keep my company, give me my way.”

- Guilt: “To be forgiven, give me my way.”

- Apathy: “To have me care, give me my way.”

- Pity: “To ease my plight, give me my way.”

- Love: “To regain my affection, give me my way.”

Any use of emotional extortion is a bad bargain because it corrupts the honest expression of intense feelings and lowers trust by using them for manipulative gain. “You’re just acting hurt to get what you want!” Parents need to avoid this behavior, and should not give in when an adolescent employs it with them.

On these occasions, simply declare to your teenager: “Instead of using your feelings to get your way, please specifically state what it is you want or do not want to have happen and we can talk about that.”

Maintaining emotional sobriety

One important challenge of parenting an adolescent is maintaining emotional sobriety—honoring hard or hot feelings with acceptance without indulging them with action. When stressed, surprised, or upset, it’s what President Kennedy called “maintaining grace under pressure,” or what I think of as exercising “adult maturity.”

When in disagreement, when criticized, when faced with the unexpected by the teenager, it can take effort not to lose one’s cool or temper, not to end up pouring inflammatory language like criticism, blame, or name-calling on the emotional fire.

Acting upset with your upset teenager only gets that young person more upset. Thus yelling at her to stop yelling only encourages yelling by adult example, because conflict encourages similarity this way.

So, in times of emotional intensity with your adolescent, model conduct you want the young person to imitate. Before reacting, take some reflection time and ask yourself:

- "What do I feel like saying and doing?”

- "What do I think is wise to say and do?”

And then choose the second over the first.