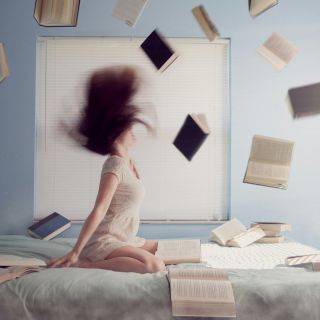

Dreaming

5 Common Recurring Dreams and What They Might Mean

Flying, being chased, losing teeth, and more.

Posted April 19, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Dreams have long held a certain mystique, captivating humanity with their enigmatic narratives and symbolism. Across both cultures and time, this aspect of our consciousness has been a constant source of fascination and interpretation.

However, through psychological research, both academics and laypeople alike are beginning to unearth the significance of dreams, as well as attempt to grasp their deeper meanings.

Psychological Perspectives on Dreaming

Dreams, arguably one of the most elusive fragments of our subconscious, occur during the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep. While the exact purpose of dreaming remains a long-standing subject of debate, researchers estimate that the average person experiences around four to six dreams per night.

During these nocturnal odysseys, our minds embark on journeys that can be as perplexing as they are revealing. However, similar to the purpose of dreams, their significance and origins have been a perpetual subject of debate.

- Freudian perspectives. Sigmund Freud, the renowned father of psychoanalysis, believed that dreams were the “royal road to the unconscious.” According to Freud, dreams are the gateway to our deepest desires, fears, and conflicts, often obscured from conscious awareness. He proposed the theory of manifest content (the literal narrative of a dream) and latent content (the symbolic meaning) concealed within. Through psychoanalysis, he sought to decode these hidden messages and uncover how our subconscious turmoil shapes our waking lives.

- Jungian perspectives. Carl Jung, another pioneering figure in psychology, offered an alternative perspective on dreams. For him, dreams aren’t a mere random manifestation of the subconscious, but rather a meaningful expression of our psyche’s quest for wholeness. Jung introduced the concept of archetypes—universal symbols that permeate human experience—and suggested dreams to be the channel through which these archetypes manifest. By engaging with our dreams, Jung believed we could make attempts at self-discovery and confront the shadowy aspects of our personalities, integrating them into a cohesive whole.

- Contemporary perspectives. In modern psychology, there are many diverse theories regarding the nature of dreams. Cognitive theories propose that dreams are a byproduct of the brain’s processing of information, serving to consolidate our memories while also reinforcing learning. Neurological research often focuses on the complex mechanisms that underlie our dreams, highlighting the role of brain activity during REM sleep. Although modern perspectives offer valuable insight, they often skirt around the profound symbolism and personal significance that dreams hold for each of us.

Common Dream Symbols and Their Meanings

Dreams are replete with symbolism, each carrying its own significance and resonance for each individual. Research from the journal Motivation and Emotion shows that, across the globe, there are multiple common motifs within our dreams. While interpretations may vary, certain themes recur across cultures and contexts:

- Falling. Likely one of the most ubiquitous dream motifs, dreams of falling often evoke a sense of vulnerability and loss of control. Psychologically, these dreams may symbolize a fear of failure or a perceived descent into personal chaos. Alternatively, falling could also indicate a need to let go of inhibitions and embrace change. Freud interpreted falling as a manifestation of sexual desires or anxieties, reflecting a longing for release or surrender.

- Flying. In stark contrast to falling, dreams of flying represent a soaring liberation from earthly constraints. Psychologically, flying dreams could symbolize freedom, empowerment, and transcendence. Jung viewed flying as a metaphor for spiritual ascent, signifying a journey towards enlightenment. These kinds of dreams often coincide with feelings of exhilaration and euphoria, and offer a glimpse of the potential within our human spirit.

- Being chased or attacked. The sensation of being pursued in a dream evokes our primal instincts of fear and evasion. Psychologically, these dreams may symbolize avoidance of confronting unresolved conflicts or emotions. It may reflect a sense of being overwhelmed by external pressures or inner turmoil. Jung interpreted these dreams as a confrontation with our shadow selves—the darker, suppressed aspects of our personalities that demand acknowledgement.

- Teeth falling out. Although strange, dreams involving the loss of teeth are surprisingly common, and they often elicit feelings of unease and vulnerability. Psychologically, these dreams may symbolize a fear of aging, loss of vitality, or concerns about self-image. Alternatively, they, too, could signify a need for renewal and rebirth, shedding old habits or beliefs to make way for growth. Freud interpreted them to be reflections of sexual anxieties or castration fears, linking them to feelings of emasculation and powerlessness.

- Public nudity. Dreams of being naked in public can lead to profound feelings of vulnerability and exposure. Psychologically, these dreams could symbolize a fear of judgment, rejection, or social scrutiny. They may reflect insecurities about self-image or a desire to conceal perceived flaws and weaknesses. Jung interpreted nudity as a stripping of societal masks and pretenses, exposing the true self beneath the façade of social conformity.

From classical to contemporary psychology, the study of dreams offers a window into the depths of our subconscious. In our own personal quests for understanding, embracing the strangeness of our dreams allows us to explore the depths of our true selves. In our dream worlds, the unconscious speaks. By listening to it, we may uncover profound truths that lay beneath the surface of our waking lives.

A version of this article also appears on Forbes.com.

Facebook image: fizkes/Shutterstock