Psychopathy

Revising My Ideas About a Kid Who Killed

Filling case holes with informed awareness can detect and repair bias.

Posted April 12, 2024 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- The earliest narratives about a crime might convey only part of a story.

- Yet psychological anchoring can “set” such stories in stone.

- Such tendencies thwart amending older cases with new research and discoveries.

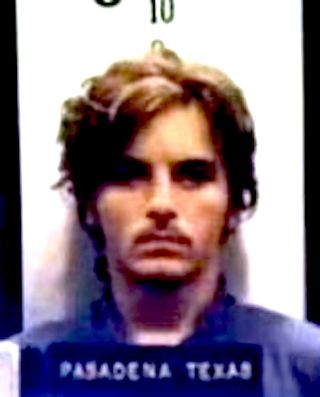

My first impression of Elmer Wayne Henley Jr. came from Jack Olsen's true crime book, The Man with the Candy. When I later wrote about Henley for publications like Serial Killer Quarterly, I thought I had a good sense of him: one of two teenage accomplices to “candy man” Dean Corll, who’d murdered at least 27 boys during the 1970s. I looked up other sources, but most had relied on Olsen’s reporting. I found some news items and a Texas Monthly article, but the shared impression was negative: Henley merited little regard as a ninth-grade dropout who’d coldly lured his friends to their deaths.

Around 2005, I watched a documentary, The Collectors, on some guys who amassed the artwork of serial killers. They’d interviewed Henley, now an artist. He seemed thoughtful and reflective, and his IQ was reported to be 126. I was intrigued. I was also learning more about neurological findings on impulsivity and the juvenile brain. I wondered if there was more to his story than the original narratives revealed.

Henley was 14 when he first met Corll in 1971 in Houston, Texas. Introduced by David Brooks, a kid already leveraged by the charming predator, Henley eventually became an accomplice in the murders of boys from his neighborhood, reportedly for money. He and Brooks also transported and buried the bodies.

I considered corresponding with Henley but put it off. After I participated in 2021 in a documentary based on my work with "BTK killer" Dennis Rader, I was invited to propose a similar project. Henley came to mind. One of the production crew, journalist Tracy Ullman, had already connected with him for something else, so she introduced us. I soon realized that my original sense of Henley was based on an incomplete narrative derived largely from deficient police reports.

Olsen had never interviewed Henley or anyone who knew him. In his book, he’d posed the police perception as the truth. Yet in 1973, when Henley killed Corll and turned himself in, the Houston detectives had displayed significant bias, ignorance, and inexperience in their reports and media interviews. Their interrogations were flawed, and they’d sometimes reconstructed conversations weeks later for official narratives, having no clue about memory corruption.

I realized I should reconsider my sense of Henley so I could fairly hear the story from his perspective. I’d learned during clinical training to let the data emerge unfiltered by a priori assumptions. That's difficult to accomplish, but it seemed necessary. I interviewed Henley for many hours. He understood that his memory was likely self-serving, and he sought no absolution of his responsibility. Still, he insisted there were facts about him that the investigators and journalists had ignored.

I pieced together a timeline with not just the police reports but also with Ullman's research and details from Henley’s account at the time. Much had happened since Olsen had published his book. There were people with something to say about those events who’d never been asked. (Ullman and I published all of this in The Serial Killer's Apprentice.)

Henley stated that Corll had misled him and then exploited his naivete to coerce him into procuring victims. He’d caved. By the time Henley was 17, he’d helped with multiple murders and believed he’d be killed, too. He'd been paid, he said, but only for one, and murder had not been part of the package. He’d tried to get help from adults he knew, but each time was dismissed. He’d tried to get away from Houston, each time failing. Finally, Henley fatally shot Corll, saving himself and two friends. When he turned himself in, he told police there were multiple victims. He volunteered to show where they were buried. For his part, Henley received six life sentences.

Our interviews turned into lengthy sessions. I had a theory about temporary psychopaths—those who partner with predators and become as callous as them, but only while under their influence. Henley initially resisted this notion, wanting to accept full blame for his “cowardice,” but as he read more research on the malleable teenage brain, he began to grasp how he’d been vulnerable to Corll’s manipulation.

In 1972, he’d truly believed there was a “syndicate” of sex traffickers that Corll knew who’d harm him should he resist what Corll required. Step by step, he said, he’d been drawn into Corll's world until he thought he had no choice. Yet, during his trial, he couldn’t claim duress because, at times, he’d been physically away from Corll. In 1974, there was little grasp of the power of psychological duress or of how vulnerable some teens can be to a skilled predator’s pressure.

According to Galoob and Sheley (2022), coercion occurs when someone threatens a target, pressuring the target to act in accordance with the threat. The coercer maneuvers the threat to regulate the target’s choices. They generally use threats, humiliation, and isolation. The target person may operate out of fear and even develop a compulsion to please.

Henley expressed this: If Dean approved, then an act was okay. It was better to yield to his authority and get his approval than to risk being harmed.

There’s clearly more to the story than the original crime journalists covered. It can be difficult to yield to a new narrative when the received one becomes entrenched. That’s the natural cognitive bias of anchoring, wherein the first set of facts presented seems the most solid. However, when the initial crime story derives from incomplete, hasty, or biased investigations, we must adjust. While evidence and corroboration should remain central, we can’t let automatic mental sets block new information that might better convey the truth.

References

Abrams, Z. (2022, July). What neuroscience tells us about the teenage brain. Monitor, 53(5). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/07/feature-neuroscience-teen-brain

Galoob, S. R., & Sheley, E. (2022). Reconceiving coercion-based criminal defenses. Journal of Crime, Law & Criminology 265, 112.

https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol112/iss2/3

Ramsland, K. & Ullman, T. (2024). The serial killer’s apprentice: The true story of how Houston’s deadliest murderer turned a kid into a killing machine. Crime Ink.