Intelligence

Turning Policy Into Practice

Merely issuing directives isn’t enough.

Posted March 17, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Organizations frequently issue policy statements about how people should carry out various activities. The policy statements are often carefully crafted, sometimes step-by-step instructions about how to do things. The military analog for these policy statements is a doctrine, the steps to be followed, and sometimes the order of those steps. The aviation community relies on checklists. The health care community compiles best practices.

These efforts provide valuable guidance. They also standardize the actions of different people, even people who may have never met, which improves coordination because everyone is intended to follow the same script. The efforts also provide quality control. There should be little debate about the benefits of these different kinds of policy statements. We should agree that in many situations, they are necessary.

However, they may not be sufficient. That’s the argument I am making in this essay. Further, too many people and organizations believe that issuing a policy is all they have to do, a delusion that leads to disappointment, frustration, and recrimination when people fail to follow that policy as intended.

What’s missing from the policy?

What’s missing are the complexities and the contextual nuances that surround us. Attempts to capture these complexities and nuances in the policy rarely, if ever, succeed because the world has more variations than we can handle, more variations than we can imagine when we formulate the policy, and more variations that emerge after we formulate the policy as conditions evolve in unpredictable ways. Trying to capture these complexities and nuances is unlikely to succeed and often is counterproductive because the effort interferes with the clear message intended by the policy.

The other three quadrants

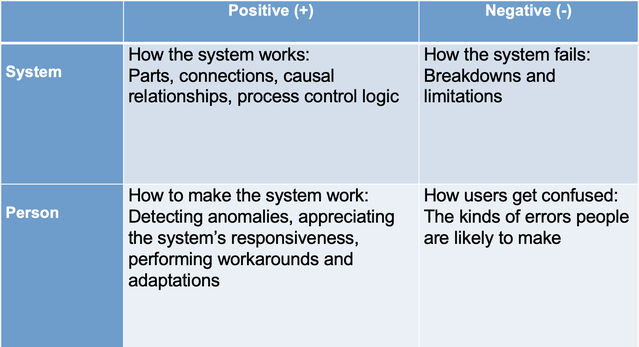

In a previous essay, Joseph Borders, Ron Besuijen, and I described a mental model matrix. We can apply that matrix to the challenge of getting policies implemented. The policy statement itself corresponds to the upper-left-hand quadrant: Here is what is supposed to happen. The other three quadrants reflect the dilemmas that often arise.

People generating the policy often ignore the other three quadrants. The policy may well have limitations, which is the upper-right quadrant. Staff members will need the experience and skills to adapt the policy to different conditions, which is the lower-left-hand quadrant. And the policymakers can try to anticipate the ways people may become confused, the lower-right-hand quadrant.

Therefore, to increase the chances that a policy can be successfully carried out, the organization might want to consider these three other quadrants and think about tactics and interventions for each of them.

Scenarios

One strategy is to devise scenarios to help workers anticipate problems and adapt to them. The "ShadowBox scenario method" that I am most familiar with (Klein c, 2016) can be used in this way, and there are obviously many other scenario techniques.

Of course, organizations will not want to go through the effort of developing scenarios for each policy. In most cases, the payoff isn’t sufficient to justify the costs and the time needed. Organizations should only take this extra step of augmenting policies with scenarios if they judge that the policy is sufficiently important and that non-compliance can have serious consequences.

But there are easier strategies to use. For example, ShadowBox Lite just presents a single decision point rather than a scenario, so that means less time and effort to develop the single decision point and recipients need much less time to engage with it.

Patient Discharge

Let’s look at a simple example. A patient is about to be discharged from a hospital after a stay of several days. The discharge nurse carefully tells the patient the after-care regimen to be followed. Perhaps the discharge nurse has printed out the procedures the patient needs to follow.

Eisenberg and Mahar (2019) argue that this routine is not going to be sufficient. Merely issuing the directions, stating the policies, and handing off the printout doesn’t ensure that the patient has grasped what needs to happen. The discharge nurse needs to go further, to judge whether the patient has grasped what he/she is supposed to do.

And I would take this further. If the discharge nurse is serious about getting the policies followed, I would suggest anticipating the kinds of confusion that the patient might have. I suggest some simple ShadowBox Lite decision points to illustrate decisions the patient might face (e.g., “You are supposed to take this liquid medication every six hours. What are you going to do if you are at work and don’t have a spoon available to measure the dose?”). The discharge nurse has the experience to understand common issues in the other three quadrants of the mental model matrix. The discharge nurse can use simple examples to get the patient thinking about post-hospital care so that the recovery can go more smoothly and to reduce the chances of having to get re-admitted.

And, of course, if the patient does have to get re-admitted, the hospital will blame the patient (not itself) for failing to follow the instructions.

Conclusion

Policies are often necessary but rarely sufficient. If organizations are serious about turning policies into practice, and if the policies are sufficiently important, then decision point exercises, even simple ones,, may have great value.

References

Klein, G., & Borders, J. (2016). The ShadowBox approach to cognitive skills training. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 10(3), 268-280

Eisenberg, E.M., & Mahar, S.E. (2019). Stop wasting words: Leading through conscious communication. Advantage Press: Charleston SC.