Neuroticism

Mass Neurosis Through the Life and Lens of Erich Fromm

Can social forces be neurotic, and how would that influence individual persons?

Posted January 7, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- As is the case with most great theorists, Erich Fromm’s theories were initiated and molded by his own subjective experience.

- Erich Fromm’s exposure to Old Testament prophetic literature composes one of the most lucid contributions to his interest in social movement.

- After World War I, Erich Fromm began to view certain social dynamics as neurotic.

- The work of Karl Marx reinvigorated Erich Fromm’s hope for an international peace as the result of many embracing a humanistic mindset.

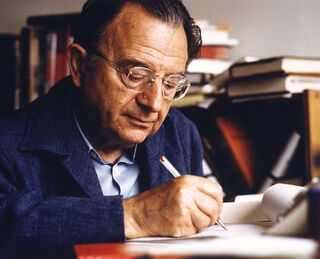

Born on March 23, 1900, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Erich Fromm was raised as an Orthodox Jew by, in his description, “highly neurotic” parents. Fromm did not hesitate to confess that he himself was “a probably rather unbearable, neurotic child” (Funk, 1999).

His father’s erudite faith and his family’s expectations regarding his faith development were significant formative forces he pushed against. Fromm (1944) concluded, “It is the defeat in the fight against authority which constitutes the kernel of the neurosis.”

Religious education and the Old Testament

Fromm’s interest in mass behavior had an overwhelming influence on his conclusions about neurosis, and his own religious education was a prime contributor to his theory of mass behavior:

"[Fromm] was especially fascinated by the prophets Isaiah, Amos, and Hosea because they had promised universal peace. As a young man, he studied the Talmud with Rabbi J. Horowitz, and later, as a university student, he took instruction from Salman Rabinkov in Heidelberg and Nehemia Nobel and Ludwig Krause in Frankfurt. The influence of these teachers was considerable: Rabinkov’s socialist and Nobel’s mystic orientation are thematically present in Fromm’s writings and fields of interest." (Funk, 1999)

Fromm’s early exposure to Old Testament prophetic literature composes one of the most lucid contributions to his interest and understanding of social movement, or mass behavior.

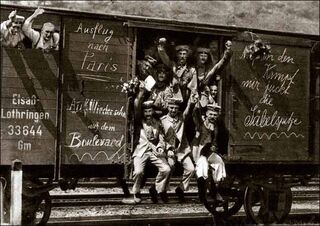

World War I and "official ideologies"

The most significant shift in Fromm’s thinking developed as a byproduct of a second factor impacting Fromm’s theory development: World War I and its psychosocial reverberations in German communities.

Fromm’s sympathy for the prophets and their messianic visions of the harmonious coexistence of all nations was profoundly shaken by the First World War, which made him increasingly distrustful of all official doctrines, including of vainglorious nationalism:

"When the war ended in 1918, I was a deeply troubled young man who was obsessed by the question of how war was possible, by the wish to understand the irrationality of human mass behavior, by a passionate desire for peace and international understanding. More, I had become deeply suspicious of all official ideologies and declarations, and filled with the conviction ‘of all one must doubt.’” (Fromm, Beyond the Chains of Illusion, 1962)

Through this disillusionment, Fromm began to view certain social dynamics as neurotic and their impact on the individual as a projection of societal dysfunction. From this point, his life's work was to better understand the cause and nature of societal dysfunction and how it affects individuals.

The influence of Karl Marx

The third great contribution to Fromm’s theory development came not as a result of family pressure or social upheaval, but his own diligent study, in which he sought enlightenment as to whether there could be hope for society at all. By no means his only literary fascination, the work of Karl Marx was likely his most influential interest. It was in this study that both his political and social interests were deepened and molded as never before.

Fromm contended that in Marx’s work, he saw “the key to the understanding of history and the manifestation, in secular terms, of the radical humanism which was expressed in the messianic vision of the Old Testament prophets” (Landis & Tauber, 1971). This reinvigorated Fromm’s hope for an international peace that he concluded would have to be won by the efforts of a great many embracing a humanistic mindset.

Fromm was motivated by the eventual “insight that the present historical situation will decide whether humanity will take rational hold of its destiny or fall victim to destruction through nuclear war” (Fromm, 1960).

Characterologies

Fromm’s years of political and social activism were followed by years of intensive effort to shed light on interrelationships between the sociological and the psychological. In the midst of those years, he developed the groundwork for a number of important characterologies. Perhaps his most important—certainly the most well-known—was a direct outgrowth of this study of socioeconomic structures’ impact on human needs as psychic necessities: Fromm’s having and being character types.

Characterizations of the “being” type, a type that encompassed the very ideals that Fromm greatly desired to be impacted in society, include being joyful about life, being productively active, being creative, experiencing oneself through one’s own powers, containing a humanistic religiosity, and loving life. In contrast, the “having” type may be depressed, passive, bored, unable to experience oneself fully, unable to fully believe in people and greater truth, and having a fear of death (Fromm, 1999).

There are clear indicators that these factors—Fromm’s early Jewish religious education, his experience of observing World War I’s societal impacts, and decades of continued, deepening sociological and psychological study thereafter—along with Fromm’s own self-confessed dispositions, held great sway in influencing his intriguing and novel take on society and its impact on the individual. As is the case with most great theorists, Fromm’s theories were initiated and molded by his own subjective experience and continue to be rediscovered by new generations facing both new and age-old societal challenges.

References

Fromm, E. (1944, August). Individual and social origins of neurosis. American Sociological Review, 9 (4), 380-384.

Fromm, E. (1960, Fall). The case for unilateral disarmament. Daedalus, 1-15.

Fromm, E. (1962). Beyond the chains of illusion: My encounter with Marx and Freud. New York: Simon and Shuster.

Fromm, E., & Evans, R. I. (1982). Dialogue with Erich Fromm. Praeger Publishing Co.

Fromm, E. (1999). The essential Fromm: Life between having and being. New York: Continuum.

Funk, R. (1999). Erich Fromm: His life and ideas. New York: Continuum.

Landis, B., & Tauber, E. S. (Eds.) (1971). In the name of life: Essays in honor of Erich Fromm. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.