Beauty

Bustles and Butt Lifts: What Won’t We Do for Beauty?

Here's how the stories we tell about beauty obscure the truth.

Posted April 19, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- There are many stories about the great lengths that people (usually women) will go to be considered beautiful.

- The beauty ideal is not ever-changing but rather normalizing, naturalizing, and homogenizing.

- Beauty matters more in today's world—and its cost is higher—than many people would like to admit.

This post was co-authored by Heather Widdows, Ph.D., and Jessica Sutherland.

What won’t we do for beauty? Paint our faces, starve ourselves to the bone, feel the burn, suck out our fat, freeze our faces, cut into our skin, and place foreign bodies—saline or silicone—into our skin and muscles. There are almost no limits to what we will risk for beauty, and risking our lives for the perfect buttock curves is just one of the latest in a long line of dangerous beauty practices.[1]

We devour beauty stories, stories about what women have done in pursuit of the body beautiful. Was the woman crazy? Or maybe, just maybe, she’s on to something, and we could do the same? These stories fascinate, enthrall, and repulse. These stories repeat cultural tropes about the trivial nature of beauty—and perhaps about the superficial characters of women who do beauty. Together, they trivialize beauty and obscure the truth about the changing way beauty is valued.

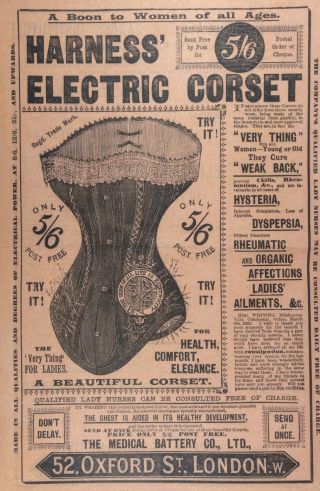

One of the stories we get told is that women—and it’s usually women in this story—have always done stupid and risky things for beauty. This is the theme of Emma Beddington’s recent article, which highlights the use of poisonous products, like white lead and radium, and terrifying machines, like hip reducers and electric corsets, to show the pains women have historically endured for beauty.[2] Sometimes, the purpose of stories like this is to show that beauty is less demanding now than in the past: “Body hair removal is nothing compared to foot-binding.” Sometimes, they aim to say that we have always done crazy things for beauty, and there is nothing really new going on. The changes in what is technically possible mean we’re moving from the bustle to the butt lift—from the “cut of the dress to the cut of the breast”—or, in this case, the cut of the buttock, literally. But in the service of the same old tired ideal.

Another story, a very common story, is to claim that beauty changes over the decades and to track these changes. The ’20s ideal was the skinny flapper, thin but no curves; the ’50s was a fuller hourglass figure, like Marlyn Monroe; the ’60s was Twiggy’s boy-like beauty; the ’80s the Amazonian supermodel; the ’90s Kate Moss’s heroin chic; and so it goes on. The moral of this story is that beauty changes across times and places, so beauty is just taste—nothing is fixed, everything is in flux.

This is a repeated story and not only in women’s magazines but also in national news outlets,[3] the tabloids,[4] and brought to life in numerous YouTube videos. This story reinforces the view that beauty changes over time and place, and so it is fleeting, a matter of changing taste. In this story, beauty can’t be pinned down: “Don’t worry if you’re not the ‘ideal’ right now; chances are, things will change, and next year, or next decade, you will be.” Either way, beauty is too ethereal, too changing, and too transient to be taken seriously.

These stories obscure the truth.

The beauty ideal is not ever-changing; on the contrary, it is normalizing, naturalizing, and homogenizing. All of the 20th-century ideals fall into the emerging global ideal. The global ideal requires that you are thin, firm, smooth, and young in one combination or another.[5] Marilyn Monroe, Twiggy, and Kate Moss are just different versions of thinness, firmness, smoothness, and youth; none challenges the core features of the ideal. To be perfect or just good enough, you don’t need to be Margot Robbie’s stereotypical Barbie, but you do need to be one of the barbies. Skin color can vary, size can vary (within limits), and in some contexts—assuming you are thin, smooth, and firm—you can even be old.

Stories about the changing value of beauty and stories that make women seem silly to risk pain for something as transient as beauty obscure the increasing dominance and demandingness of the new global ideal. A new—and very popular—story is that beauty is increasingly diverse. Diversity is the story we want to tell most right now. For example, the May 2018 Vogue cover overtly celebrates diversity.[6]

Diversity in skin color has been embraced by fashion—and this is an important step forward to be championed and celebrated. Absolutely amazing. However, diversity in skin color does not challenge the emerging beauty ideal. The ideal skin tone of the emerging beauty ideal is mid-toned—golden, bronzed, or olive (often attained by lightening dark skin and tanning pale skin). But any skin color can be beautiful as long as you have the other features of the ideal—thinness, smoothness, and youth.

The Vogue cover models are more similar than they are different. Not only are they all thin with curves (they all go “in” in the right places), but they have the luminous, ideal skin that smoothness and firmness require. Skin which glows—newsflash, skin doesn’t glow in the real world, only in the virtual world—but it is glowing skin, glass skin, that is required. This isn’t real human skin: It’s the skin of photos, selfies, filters, and editing apps, skin without pores, blemishes, or imperfections. Enninful claims diversity isn’t just about skin color: “When I say diversity, I want to be clear that it is never just about black and white for me. It’s about diversity across the board—whether that’s race, size, socio-economic background, religion, sexuality.” [7]

But is this really diversity in terms of the demands of the global ideal? Real diversity would be models that are fat, hairy, pockmarked, and old, and with more than one feature challenged at a time. Any and all bodies would be visible on magazine covers and in the virtual world. Only this would actually challenge the ideal. The story of diversity is just the last in a long line of stories that obscure the truths of beauty.

Beauty isn’t fleeting, transient, or trivial. It never has been. The women who wore the electrical corset might not have known the full risks, but you can bet your life they didn’t enjoy the practice and wished they didn’t feel compelled to engage—but they knew beauty mattered. In our brave new world, which is increasingly a visual and virtual world, beauty matters even more, and for the first time, our beauty ideal is global.[8] A global ideal is far less forgiving and, despite the rhetoric, far less diverse than our past ideals (whatever crazy practices they required). To take beauty seriously, we need to reject these stories—however compelling and familiar they are—and take a cold, hard look at just how serious beauty’s demands are and the challenges of living under a global ideal in a virtual culture.

Heather Widdows is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Warwick.

Jessica Sutherland is a Research Fellow in the Politics and International Studies Department at the University of Warwick.

References

[1] Widdows, Heather 2018, ‘Dying for the Perfect Butt’, Psychology Today (https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/perfect-me/201810/dying-the-perfect-butt)

[2] Beddington, Emma 2024 ‘Shock of the Old: 10 Painful and Poisonous Beauty Treatments’. The Guardian. (https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/jan/04/shock-of-the-old-10-painful-and-poisonous-beauty-treatments)

[3] Howard, Jacqueline 2018, ‘The history of the ‘ideal’ woman and where that has left us’ CNN (https://edition.cnn.com/2018/03/07/health/body-image-history-of-beauty-explainer-intl/index.html)

[4] Greep, Monica 2022 ‘How the ‘perfect body’ has changed throughout the decades. MailOnline. (https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-10467643/How-perfect-body-changed-decades.html)

[5] Widdows, Heather 2018 Perfect Me: Beauty as an Ethical Ideal Princeton University Press.

[6] Enninful, Edward, 2018 ‘9 Trailblazing Models Cover May Vogue’ Vogue. (https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/may-cover-vogue-2018)

[7] Enninful, Edward, 2018 ‘9 Trailblazing Models Cover May Vogue’ Vogue. (https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/may-cover-vogue-2018)

[8] Widdows, Heather, 2018 A Duty to be Beautiful? (https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/perfect-me/201807/duty-be-beautiful)