Anger

4 Emotions for Surviving & Thriving in an Uncertain America

... And One To Avoid

Posted December 19, 2016

When you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

When you are an emotion scientist, you view all the world through the lens of feelings.

I’ve hesitated to blog post-election because my writing style leans light and irreverent, and in the past month my thoughts and feelings have run instead rather dark and reverent.

I’ve also been reading, and reading, and reading, wonderful posts by historians, journalists, and sociologists, posts full of nuanced analysis and thoughtful expertise. Post by people who can speak so much more eloquently and knowledgeably than me about the best path forward for people who care deeply about human rights and the environment and democracy.

I don’t want to meet those earnest, important contributions with a chatty listicle.

Yet, like Flannery O’Connor, “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.” And I’ve been struggling with which emotions to allow free rein and which to curtail, how to regroup and move forward.

I’m not the only one. In a recent piece in reaction to the Russian hacking of the election, journalist Paul Krugman mused about how to manage his anger productively: “Personally, I’m still figuring out how to keep my anger simmering — letting it boil over won’t do any good, but it shouldn’t be allowed to cool. This election was an outrage, and we should never forget it.”

So what follows is framed around which emotions psychological science suggests might be helpful for the path ahead, at least for those of us who are worried about the accumulating signs that dark times are encroaching. But what it really is under the surface is a reading list of some of the most thoughtful contributions I’ve run into in these waning weeks of 2016.

If you’d prefer the list straight-up, I’ve posted it here.

ANGER

Anger is a curious emotion. Most negative feelings involve withdrawal or avoidance. Fear inspires you to run away, disgust leads you to recoil, shame encourages you to hide your face.

Positive emotions, on the other hand, encourage approach — an extended hand of friendship, an embrace of affection, a leap into new opportunities.

The surprising thing about anger is that most people find it unpleasant, but yet it pushes us toward approach, not avoidance. You want to lunge forward, to strike, to right a wrong. You experience a surge of adrenaline, a boost in motivation.

Interestingly, when you perceive you have been wronged, whether you feel anger — instead of a withdrawal emotion like fear or disgust — depends on how in control of the situation you feel.

Moreover, research by Maya Tamir and others suggests that anger may benefit performance in confrontational games or negotiations. For instance, her data suggests that participants who choose to listen to aggressive music or recall an angry memories (versus soothing music or a memory that doesn’t involve anger) perform better on a subsequent aggressive video game.

So anger may be, as Paul Krugman suspects, productive. It can fuel goal-directed behavior, suggests that you feel some control over the situation, and may benefit confrontations.

Philosopher and professor George Yancy writes marvelously of the productive aspects of anger in his post called “I Am a Dangerous Professor.” He wrote the post in reaction to being added to the now-infamous “Professor Watchlist,” which catalogues professors of left-leaning tendencies for the far right to avoid or (presumably) otherwise target.

The anger I experienced was also — in the words the poet and theorist Audre Lorde used to describe the erotic — “a reminder of my capacity for feeling.” It is that feeling that is disruptive of the Orwellian gestures embedded in the Professor Watchlist. Its devotees would rather I become numb, afraid and silent. However, it is the anger that I feel that functions as a saving grace, a place of being. — George Yancy

Hang on to your anger. For we must “spin our newfound rage into action.”

In a post called Why Dictators Don’t Like Jokes, Srdja Popovic tells a story about being part of a (at the time) teeny resistance movement in Serbia called Otpor. He and a number of student resistors staged a protest in which shoppers in a district could pick up a bat and unleash some steam on a barrel mocked up with a taped picture of Serbian dictator Slobodan Milošević. Neither the barrel nor the swinging nor the steam-releasing proved to be critical in the movement, however. What turned out to be critical was that Milošević’s police showed up and, helpless to identify any single perpetrators, arrested the barrel. Photos of the police struggling to get the arrested barrel to the police car hit social media and people started laughing instead of quivering in fear.

After this and similar acts of protest humor began to spread, Otpor exploded from a handful of activists to a national movement with 70,0000 followers. Popovic claims: “Once the barrier of fear had been broken, Milošević could not stop it.”

Because power, ultimately, is largely a perception.

“In a room sit three great men, a king, a priest, and a rich man with his gold. Between them stands a sellsword, a little man of common birth and no great mind. Each of the great ones bids him slay the other two. ‘Do it,’ says the king, ‘for I am your lawful ruler.’ ‘Do it,’ says the priest, ‘for I command you in the names of the gods.’ ‘Do it,’ says the rich man, ‘and all this gold shall be yours.’

So tell me- who lives and who dies?”

Tyrion cocked his head sideways. “Did you mean to answer your damned riddle, or only to make my head ache worse?”

Varys smiled. “Here, then. Power resides where men believe it resides. No more and no less.”

“So power is a mummer’s trick?”

“A shadow on the wall,” Varys murmured, “yet shadows can kill.” — George R.R. Martin

Both power and fear rely at least in part on perception — the idea that someone else is in charge of your destiny and that they possess the capacity to harm you. That you are helpless.

Humor disarms power by disabling fear.

If you laugh at someone, they become small and you become large. That is why taunting is the weapon of choice of so many school-yard bullies. And why so many yarns about bullies brought low involve the tables being turned so that they are the target of mockery.

But humor can do more than pull the rug out from under fear and thus diminish the power of a bully or authoritarian. Shared laughter also can serve as social glue, encouraging unity and positivity, and it can portray members of a movement as people you want to spend time with rather than boring, deadeningly serious types. “Make a protest fun,” says Srdja Popovic, “and people don’t want to miss out on the action.”

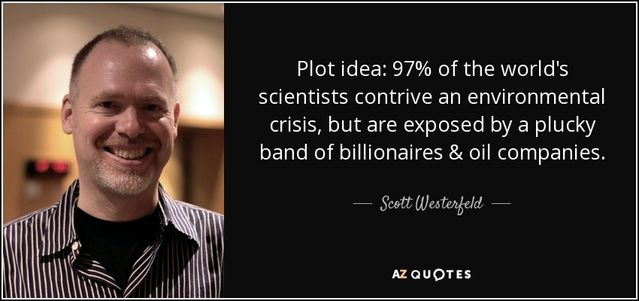

Finally, something is funny because you detect some inherent contradiction or incongruity. Many classic jokes operate on the basic design of being led down one garden path, only to realize you were on an entirely different path all along. Because of this, humor can often cut to the heart of a complicated issue more quickly, more decisively, and more persuasively than a giant stack of think pieces.

S

So be sure to contain some “laughtivism” in your activism.

PRIDE

Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist and author of the book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. While there are some points on which he and I disagree, I find his arguments on how the right and left approach morality compelling. He argues that there are five essential foundations to morality and that conservatives and liberals differ in the weight and value they attribute to these foundations. Namely, liberals put far more value on the foundations of harm and fairness than any of the other foundations, whereas conservatives care far more about loyalty, authority, and purity than do liberals.

Haidt argues that a well-functioning society needs a balance between the forces of liberalism and conservatism — that we need both agents of change and defenders of stability.

In an interview with TED’s Chris Anderson filmed right before the U.S. presidential election, Haidt discusses how conservatives are “drawbridge-uppers” and liberals “drawbridge-downers.” He joins other voices like Mark Lilla and Bernie Sanders in an argument that the left’s increasing focus on so-called “identity politics” has resulted in those on the right yanking hard on their drawbridges, and that to return to a less restrictive political environment, we need to abandon these supposedly divisive arguments.

Many scholars have leapt to answer these arguments vociferously, and I will let their words stand here as counter-argument.

But to my mind, it is also important to remember that we all have multiple identities —for instance, I am at the same time a female, an academic, and a geek. These are all tribes to which I belong, and my friends and family members and neighbors share some of these identities but not others.

I think there is way that we can answer Haidt’s call to understand and leverage the psychology of in-groups and out-groups without calling for the most vulnerable among us to shut up about their desire for basic human rights while we appeal to the white working class.

Namely, we could activate our shared identities as Americans, calling on pride and patriotism.

As one of those “coastal, liberal, latte-sipping, politically correct, out-of-touch folks” everyone loves to hate on these days, I’ve never been drawn to outward displays of patriotism. I tend to be more embarrassed than proud of America’s global reputation of being sort of scrappy and crass, itching for a fight. But when Kellyanne Conway suggested that Senator Harry Reid be “very careful” about criticizing Trump, and journalist Kurt Eichenwald broke professional demeanor by tweeting, “F*ck you, this is America”? … I yelped and clapped.

I’ve never found American democracy to be quite as beautiful as I do these days, the very concept that individual voices select representatives, who then are beholden to the wishes of these voices. That it matters when you call your representative to express your fervent hopes for how they might govern — at least, it does when we do it en masse.

Perhaps we can dissolve some of the divisions between right and left by remembering our shared points of pride: our freedom of thought and expression, that no one can tell us what to do, our strength as a melting-pot of beautiful diversity.

By recalling and feeling pride in the sentiment: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Ian Leslie wrote a wonderful post about how “status anxiety” may have fueled both Brexit and the rise of Trump. He muses that in both cases, the left might have benefited by injecting their messages with more patriotism. For “[p]atriotism is a great equaliser of status, a universal basic self-esteem.”

AWE

All of these emotions are affective states for effective resistance: anger, humor, and pride.

One of my personal struggles has been to fight emotional exhaustion. To figure out how and when to turn off the flood of bad news. How to remain vigilant — and I do feel that it is my personal responsibility coming from a position of privilege to remain vigilant— without burning myself out.

There are many ways to shore up emotional reserves, but my personal favorite is awe. Awe is a complex emotional reaction activated when an encounter leads to a sense of enormity. You feel small but also amazed. Your jaw may drop, goosebumps rise on your skin, you sharply intake breath, tears may come to your eyes. Awe-inducing experiences also require you to adjust or accommodate your view of the world to make room for this new experience or information.

Astronauts report it when seeing Earth from space for the first time. Hikers feel it when scaling giant peaks. Scientists report it when sensing the vastness of what we still don’t know.

A friend of mine and I fight about whether awe is actually an emotion. I took this battle to my classroom this semester, asking my students to debate whether awe was an authentic emotional reaction deserving its own category, or instead just a collection of reactions that sometimes occur together. One of my students summed it up well by saying, “I studied abroad in Rome last term. When I walked into the Sistine Chapel, I looked up, and tears just fell from my eyes. That’s not the same emotion I feel when, say, encountering a really excellent burrito.”

That’s awe.

Research by psychologists Lani Shiota and Dacher Keltner, among others, has demonstrated that the experience of awe broadens our cognitive perspective and enhances well-being.

Soon after the election, I ran into this video of manta rays jumping in the ocean.

Watching the video, I felt reassured on multiple levels. Because this moment in our political history means nothing to these manta rays. The privileged bubble I’ve lived in for most of my life is unusual. Life goes on, and there is still great beauty in the world. All of these realizations were rejuvenating for me.

So whatever gives you good awe, seek it out. Get out in nature. Attend art shows. Read science. Replenish.

AVOID FEAR

The one emotion we don’t need, that we need to resist, is fear. Fear results in either paralysis or flight, and neither behavior will benefit anyone.

I won’t look away from the fear-inducing posts, because we might need the information they contain. Thus, Masha Gessen’s Autocracy: Rules for Survival was an early and important call to resist the calls to pretend we just experienced a normal election, to avoid the path of “Ted Cruz, who made the journey from calling Trump ‘utterly amoral’ and a ‘pathological liar’ to endorsing him in late September.”

But then I read in Timothy Snyder’s 20 Lessons from the 20th Century on How to Survive in Trump’s America: “Remember that email is skywriting” and I freeze and think of all my tweeting and ‘booking and emailing and worry that I may be putting myself at risk, my family at risk.

But this same post lists as Rule #1: “Do not obey in advance.” Every step we take back in fear is an emboldened step potentially autocratic powers can take forward.

So when I feel those icy fingers of fear and consider back-spacing over tweets or posts or sentences in a blog, I remember: "This is America."