Environment

Sacrifices, Sacrificial Lambs, and Scapegoats

What and why we sacrifice and are sacrificed.

Posted June 6, 2017

In the first episode of American Gods, a Viking party discovers a new land (America). One of their members is immediately killed by a barrage of arrows and the remaining Vikings find the land tough and inhospitable. Eager to return home, they cannot set sail due to the lack of wind. In an effort to change their fortune, they began making offerings, sacrifices to the Allfather (Odin), their most important deity. They start by carving and burning a wooden idol, but this accomplishes nothing. Resources depleted and becoming desperate, they increase the degree of sacrifice. Next, they stand in a line and one-by-one blind themselves in the right eye with a red hot wooden stake. Then, they try burning one of their own party alive and a breeze begins. Believing they are making progress, they divide into two teams and fight each other to the death. Midway through the battle, the winds pick up and finally they return home. The scene contains many of the essential elements of the concept of sacrifice (contemporary examples are The Hunger Games series and short story “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson).

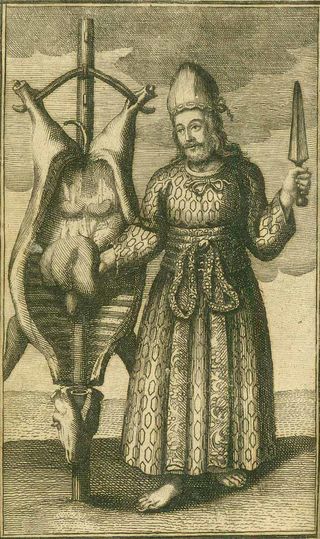

Whereas an offering is a bloodless sacrifice of food or something physical and a libation is an offering of liquid, a sacrifice carries with it the idea of a ritual killing of an animal or human. We can locate the concept of the sacrifice in numerous mythic traditions; what they all have in common is that they are either an attempt at appeasement or a tradeoff of something now for something greater later (regeneration or an increase in power). In some cultures a king or a representation thereof is sacrificed to guarantee the continuation and livelihood of the kingdom or tribe. The Aztecs engaged in human sacrifice both on a daily basis (to aid the sun in rising) and on a widespread scale (they regularly sacrificed thousands for events like the dedication of a new temple). In the classical era, we have examples such as Iphigenia. Her father Agamemnon must sacrifice her in order to satisfy Artemis. He has killed a deer in one of the sacred groves of Artemis and in retaliation she blocks the winds necessary to travel to Troy. In some accounts, she is sacrificed, in some she is saved, and in some a deer or goat is substituted for her. During the Roman Empire there existed a set of practices known as the taurobolium in which a bull was sacrificed above a pit containing the initiates who were then baptized in a rain of bull blood and body.

Although globally and chronologically there is no linear movement away from human to animal to symbolic sacrifices, we can see a lessening of—thought not end of it—to a large degree for various reasons. There is a very practical reason in that humans and animals are resources and widespread sacrifice is counterproductive to building, maintaining, and expanding a strong nation. Also, rulers were not always thrilled at the inevitability of being killed at the end of their reign, and although some commoners bought into the idea of sacrificing themselves and were even treated as celebrities, for many the prospect of being thrown off a cliff, burned, entombed alive, eaten, or what have you did not always bring elation. And if, according to one theory, one of the points of festivities and rituals surrounding sacrifice is to alleviate guilt on the part of the participants in the killing, such guilt is lessened if one sacrifices a lamb or better yet offers a bowl of honey instead of killing a human being.

Now we arrive at the concept of the sacrificial lamb and the scapegoat. A scapegoat is someone who dies for the benefit of a society, who takes on society’s collected sins. Outcasts were often used a scapegoats, presumably because no one cared about them. Kept on hand as offerings at yearly festivals or for when a drought, plague, or other difficulty afflicted the city, they were then exiled or stoned. More recent times have seen plenty of examples of scapegoating. The Holocaust or Shoah was an example of mass scapegoating leading to genocide and extermination. The us versus them mentality exists in our own moment with its talk of walls and wars and travel bans. In addition to scapegoating of entire nations or peoples or ethnicities, there exist examples of micro-scapegoating that occur, for example, in the home environment or the workplace. Scapegoat theory in social psychology explains that we use others as a scapegoat and blame them for our own problems. Unfortunately, this process often leads to feelings of prejudice toward the person or group that is being blamed. Remember that scapegoating involves an unfair system of rewards and punishments practiced by one group or person with power over another group or person. Such punishments can include exile, ostracism, relocation, taking away resources, and other such injustices on a global or even an individual scale. Scapegoating can occur for a number of reasons: as learned behavior, as a response to a misperception of a threat to power, jealousy, as an ineffective and improper attempt to regulate a dysfunctional environment, as a misguided method to cop out of and avoid addressing a different problem, the feeling that someone must be made to “pay” for some act, and as a transference of blame. In short, micro or individualized scapegoating involves isolating a small group or one person as way to avoid examining the larger, dysfunctional pattern or system—the bigger sickness that then goes untreated.

A closely related version of the scapegoat in psychology is the identified patient. This someone has been selected to represent the difficulties of the group, often a family. While the identified patient often manifests the negative behaviors of the group, he or she is often the first to seek help, speak out about what is going on, and, consequently, punished by the group or head of the group for doing so. The identified patient, then, becomes a way for the group to project its inadequacies, its failings, its problems onto the identified patient and away from itself. Doing so is a reactive, rather than proactive, maneuver and strategy by which the group hopes to avoid addressing, claiming, and then changing its own behavior.

So we must always ask ourselves several questions. When we condemn another person or group are we doing so because they are actually in the wrong or it is a way to make them carry the burden of our own issues and mistakes and make us feel better about ourselves? When judgement comes down against us, do we actually deserve it, or are we victims, forced to absorb and answer for the flaws of some other entity? Is there a better way?