Grief

Should Parents “Move On” After Their Baby Dies?

How “moving on” became a thing—and why it’s really not.

Posted February 7, 2019

When parents experience the death of a baby—at any time during pregnancy, birth, or early infancy—many of us cannot comprehend the depth of the parents’ bond and their grief. We may wonder, “What’s the big deal? Just move on and have another!” And grieving parents marvel at how clueless we are.

Why are we so out of touch with how deeply parents can be affected by the death of a baby?

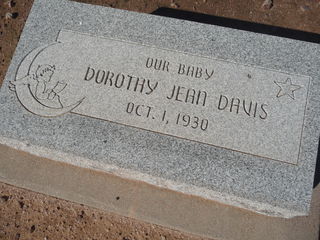

We didn’t used to be. Before the 1900’s, birth and death typically happened at home. Bereaved parents were able to spend time with their baby, taking care of the body until interment. Family and friends could stop by to pay their respects and witness the parents’ devotion. Mourning was expected and rituals gave meaning, comfort, and memories.

But by the mid-1900’s, modern medicine in the U.S. had pushed birth and death out of the home and into the hospital. Lives have been saved and extended, but this shift turned family events into medical events. At first, there was no room for traditional wisdom, longstanding rituals, or even loved ones at the bedside. As a result, these monumental life transitions became unfamiliar, and often feared.

Over the past five decades, we’ve been slowly reclaiming our birthing experiences and the care of our newborns. Many parents no longer tolerate or request hyper-managed deliveries, fathers aren't banished to waiting rooms, and newborns aren't routinely carted off to the nursery.

But we’re lagging behind on reclaiming the care of our dying and dead. We still consider death out of our reach. We typically hand over our loved ones way too soon to medical professionals, morgues and funeral homes. And we’ve paid a great emotional price, particularly when the dying and dead are our babies.

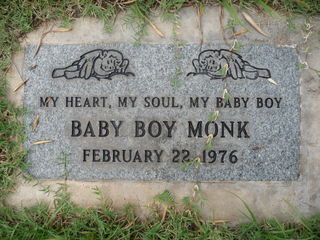

If parents aren't supported during their baby's dying and/or after their baby's death, they may hand over their baby too soon. Time cut short robs them of critical opportunities to express their devotion through caregiving, including examining, bathing, holding, and simply spending time with their baby. Shocked, grieving parents can benefit from being with their baby's body over the course of several days or more, so they can determine what is meaningful to them. For some parents, taking their baby home is especially important. Expressing their love in tangible ways—which includes making memories, gathering keepsakes, and memorializing their baby—can be enormously therapeutic for parents as they endure their complex journey of parenting, grief, and mourning.

Modern medicine in the U.S. also tends to isolate bereaved parents during the period they're with their babies. So another critical piece for parents to reclaim is inviting friends and relatives to meet the baby and be folded into the parents’ support network.

Why is this so important? When we can witness parents taking care of their little baby, expressing their devotion, and mourning deeply, we can more clearly see the parents as parents and behold this baby as their baby. Witnessing this tableau firsthand helps us truly understand this baby’s importance, the tragedy of this death, and the profound effect on the parents, all of which enables us to be supportive, including affirming this baby and validating the parents’ profound and lengthy grief. Unfortunately, when we don’t get to witness it, we often cannot imagine it, and then we are prone to misunderstanding it.

This isolation and misunderstanding ties into a second reason we’ve become clueless: we live in a fast-paced, “snap-out-of-it” culture. We see "strength" as the ability to maintain a stiff upper lip, look ahead into the future, and not cry over spilt milk. Especially after a tiny baby dies, we tend to assume the parents’ adjustment should be smooth, quick, and easy. They should be able to "move on" after a few months, right? Click, drag, done!

In fact, some people—including professionals—consider it detrimental for parents to continue thinking about and feeling connected to their baby for more than several months, and certainly beyond a couple years or so. And because we’re so isolated from birth and death, we buy into the myth that by ruminating, parents are only making themselves sadder than they need to be. We assume it’s healthier for parents to detach from “this baby that never was,” or at least distract themselves with positive thinking so they can “get over it” and “get on with life” in a timely manner. "Moving on ASAP" is seen as a reasonable and worthy goal.

But many bereaved parents report that “moving on” is impossible.

Why is moving on impossible?

To “move on” is to close a chapter. Moving on is what we do after we break up with a lover, after we get fired from a job, after we lose a cellphone. Lovers can be outgrown, jobs can be a bad fit, and phones can be replaced. Moving on is adaptive and allows for full recovery. Moving on also means forgetting, or perhaps having only a fleeting or distant memory with no emotional load.

Many parents report that there is no "full recovery." There will always be somebody missing. Emotion will always accompany the memories. Moving on would be akin to driving off and watching their baby disappear into the past as they glance at the rearview mirror. This is unthinkable. And especially for the mother, it’s biologically out of the question. Many a mother reports feeling wired for nurturing, as if every cell in her body cries out for this baby. In fact, "moving on" can be maladaptive when a baby dies. Parents tend to invest in each child as unique, and fold him or her into their family no matter how long that little life gets to live. That's why they don’t want to forget. They can’t. And they don’t want to “move on.”

But fear not. Parents are also resilient. Over time, as they grieve and mourn, they can experience a transformational healing without having to "move on."

Many parents discover that healing means gradually letting go of what might have been and adjusting to what is. In time, their anguish softens and naturally fades to the background, and they can reorient to life. But they don’t necessarily “move on.” They may continue to hold tight to that heartfelt connection with their baby. They may continue to cherish their memories and keepsakes. And they may always feel a twinge of grief when they think of their baby. That’s because they will always honor that little life, and they will forever be their baby’s mother or father.

Parents don’t move on; they simply learn to lean into life again, with their babies still tucked into their hearts and minds.

The next post looks more closely at the parent's grief and adjustment.