Hormones

Fake Sex Hormones: Chemicals Damage Health and Reproduction

Synthetic substances that mimic steroids have insidious side-effects.

Posted December 14, 2017

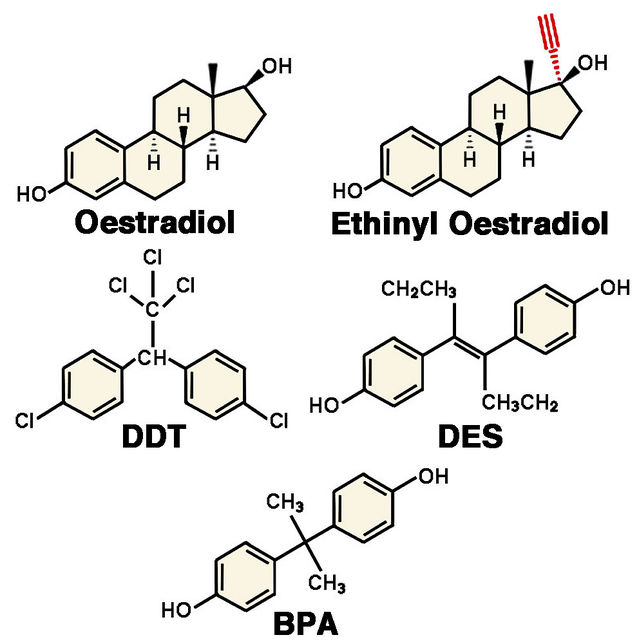

Notably as a spin-off from the petroleum industry, artificial carbon-based chemicals are rife in modern industrialized environments. Many of those organic compounds act as endocrine disruptors, fake hormones that interfere with natural body controls. Especially common are chemicals that mimic the effects of oestrogens, steroid hormones prevalent in females. In addition to disrupting development, endocrine disruptors can cause cancers of reproductive organs (breast, ovary, womb, testis, prostate gland). Two prominent examples—the efficacious pesticide DDT and the “wonder drug” DES—were outlawed in the 1970s because of their dreadful side-effects. Yet, far from eliminating the problem, such bans have been overtaken by many new endocrine disruptors.

Synthetic organic pesticides

In the long-running saga surrounding fake hormones, Rachel Carson’s influential 1962 book Silent Spring was a game-changer, effectively kick-starting the environmental movement. Originally trained in marine biology, Carson’s main target was DDT and other synthetic pesticides that became widely used after the Second World War. Creation of America’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970 directly resulted from the lively controversy triggered by Silent Spring. The EPA’s first major initiative was a nationwide ban on agricultural use of DDT in 1972. Carson focussed particularly on effects of pesticides on wildlife, but DDT and similar chemicals also stealthily undermined human health. In 1964, aged only 56, Carson herself succumbed to breast cancer, another victim to a steadily increasing scourge of women.

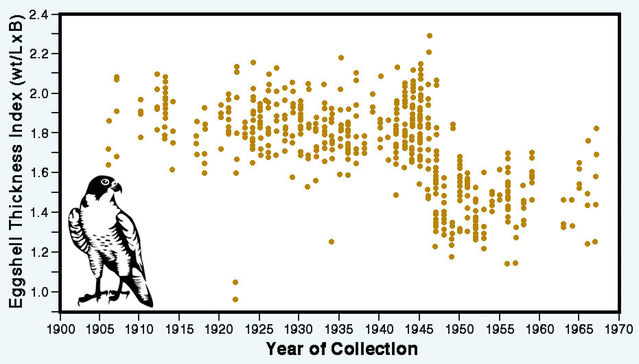

Inspired detective work documented disruption of reproduction in wild animals, yielding circumstantial evidence of DDT’s harmful side-effects. In a seminal Nature paper in 1967, Derek Ratcliffe reported sharply increased numbers of broken eggs in nests of certain predatory birds in Britain: peregrine falcons, sparrowhawks and golden eagles. Eggshell strength plummeted between 1945 and 1950 and then stayed low. Noting that geographical variations matched “the developing regional pattern of contamination by chemical pollutants during this period”, Ratcliffe listed persistent organic pesticides that had been detected in predatory birds. These included DDT (along with its breakdown product DDE), dieldrin, heptachlor, and lindane. But evidence directly linking eggshell thickness to pesticides remained elusive.

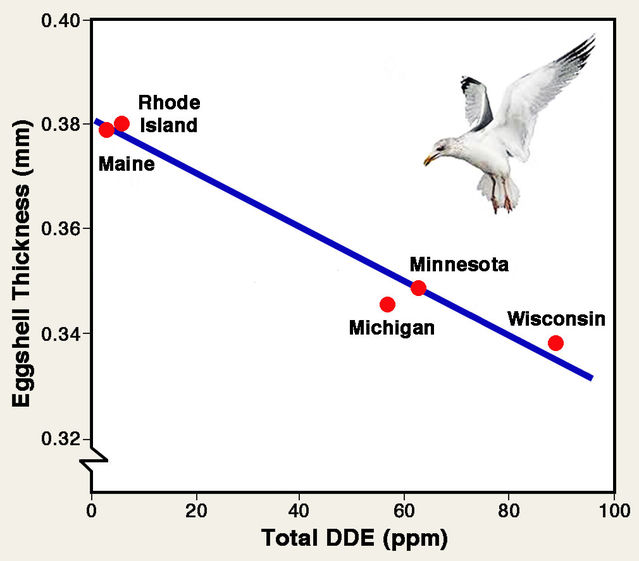

In 1968, Joseph Hickey and Daniel Anderson followed through in a Science paper examining changes in eggshells of predatory birds in the U.S. They reported unparalleled “catastrophic declines” in natural populations of birds of prey, notably peregrine falcons, bald eagles, and ospreys. Hickey and Anderson carefully checked more than 1,700 blown eggs in 39 in museums and private collections and directly measured eggshell thickness. In the three main study species, eggshell thickness remained steady over the 56-year period 1891 to 1946 but decreased sharply by around 20 percent between 1946 and 1952. High concentrations of organic pesticides in the eggs of wild birds of prey, combined with the shared timing of declining eggshell thickness and increased agricultural use of DDT, suggested a causal link. As a direct test of this link, Hickey and Anderson analyzed 57 eggs collected from herring-gull colonies in five different US states in 1967. Eggshell thickness showed a tight linear decline with increased levels of the breakdown product DDE. By contrast, Hickey and Anderson found no fluctuation in eggshell thickness in any eggs collected before 1947. Experiments conducted by Jeffrey Lincer with American sparrowhawks subsequently confirmed a direct connection between DDT and fragile eggshells.

The quest for synthetic estrogens

Although attracting less public attention at the time, equally insidious developments accompanied the hunt for an artificial substitute for oestrogens. Production of natural oestrogens for medical purposes was prohibitively expensive, so in 1930 British biochemist Edward “Charles” Dodds embarked on a systematic search for a surrogate oestrogen that could be produced at far lower cost. He methodically tested many organic chemicals to find out whether they acted like oestrogens. His standard approach was surgical removal of the ovaries from female rats, rendering the womb and vagina inactive. If injection of a test substance re-activated the female tract, an oestrogen-like effect was indicated.

In 1936, the Dodds team published a list of 15 substances that acted like natural oestrogens. Surprisingly, those substances had only two carbon rings, whereas all natural steroid hormones have four. The list included a compound now generally known as bisphenol A (BPA). However, Dodds and colleagues soon lost interest in bisphenol A and allied compounds. Together with Robert Robinson, Dodds synthesized diethylstilbestrol (DES), which proved to have a far more potent oestrogen-like effect. In 1939, the UK Medical Research Council approved DES for treatment of various reproductive problems in women, including failure to menstruate, menstrual pain and menopausal disorders. In 1941, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the drug for similar uses in the U.S. As from 1949, DES was also employed in the U.S. and Europe in attempts to prevent miscarriage and premature birth, thus extending its use to pregnant women.

Almost from the outset, various findings indicated that medical use of DES as a substitute oestrogen was ineffective and hazardous. However, warnings were largely ignored and DES was used extensively in the U.S. and Europe to treat women, including several million during pregnancy. Then, in 1971, Arthur Herbst and colleagues reported a cluster of eight cases of a vaginal cancer—clear cell adenocarcinoma—in young women. The cases examined were very unusual because this cancer is exceedingly rare and typically occurs only in women of advanced age. Detective work by Herbst and colleagues revealed that the mothers of seven of the young women had been treated with DES during pregnancy. Soon after, the FDA withdrew approval for treatment for pregnant women in the U.S. It is now well established that DES can cause multiple medical problems in individuals exposed in their mothers’ wombs, often called "DES daughters" or "DES sons." Nancy Langston’s superbly researched 2010 book Toxic Bodies eloquently recounts the tragic history of DES.

The threat continues

In the U.S., administration of DES to pregnant women was discontinued in 1971 and agricultural use of DDT was banned in 1972. Regrettably, because of impacts during pregnancy, disruptive side-effects of DES and DDT lingered for decades and persist, to some extent, even today. But we have every right to expect that appropriate safeguards should have been introduced to avoid recurrences of similar catastrophes. Although much has been done to gather and present the facts, most thoroughly by Theo Colborn and colleagues in Our Stolen Future (1997), controls are still woefully inadequate. Nowadays, we are exposed to literally dozens of endocrine disruptors— fake hormones—that damage our health and disrupt our reproduction. While individual chemicals may have weaker effects than DES or DDT, the overall cocktail to which we are exposed is undoubtedly very potent. Current endocrine disruptors include numerous plasticizers, insecticides, fungicides, adhesives and other unnatural organic compounds.

Perhaps the most flagrant example of a widespread modern-day endocrine disruptor is BPA. (See my June 11, 2013, post Spectators on Steroids.) Although DES was banned, industrial uses of BPA quietly proliferated in the background. Today, over five million tons are now used worldwide every year. The variety of uses is staggering: Hardened plastic containers for water, milk and beverages, epoxy resins (also used to in dental work), coating for heat-transfer printing of receipts, internal lining of food cans and copper water pipes to prevent corrosion, medical devices, automobile components, glazing materials, sports equipment, DVDs, sunglasses. Yet literally hundreds of experimental studies of laboratory rodents and epidemiological investigations of human exposures have convincingly shown that BPA acts as an endocrine disruptor. Most importantly, it is abundantly clear that the worst effects, at extremely low doses, derail embryonic and fetal development in the womb. And BPA is just one of the many alien synthetic substances that we all carry in our bloodstreams.

References

Bailey, R. (2004) DDT, Eggshells, and me: Cracking open the facts on birds and banned pesticides. http://reason.com/archives/2004/01/07/ddt-eggshells-and-me

Colborn, T., Dumanoski, D. & Myers, J.P. (1997) Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening our Fertility, Intelligence and Survival? New York: Dutton.

Dodds, E.C., Golberg, L., Lawson, W. & Robinson, R. (1938) Oestrogenic activity of certain synthetic compounds. Nature 141:247.

Dodds, E.C. & Lawson, W. (1936) Synthetic oestrogenic agents without the phenanthrene nucleus. Nature 137:996.

Herbst, A.L., Ulfelder, H. & Poskanzer, D.C. (1971) Adenocarcinoma of the vagina: association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. New England Journal of Medicine 284:878-881.

Hickey, J.J. & Anderson, D.W. (1968) Chlorinated hydrocarbons and eggshell changes in raptorial and fish-eating birds. Science 162:271-273.

Langston, N. (2010) Toxic Bodies: Hormone Disruptors and the Legacy of DES. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lincer, J. (1975) DDE-induced eggshell thinning in the American kestrel: A comparison of the field situation and laboratory results. Journal of Applied Ecology 12:781-793.

Maffini, M.V., Rubin, B.S., Sonnenschein, C. & Soto, A.M. (2006) Endocrine disruptors and reproductive health: The case of bisphenol-A. Molecular & Cellular Endocrinology 254:179-186.

Maffini, M.V., Sonnenschein, C. & Soto, A.M. (2011) Early life exposure to bisphenol A and breast neoplasia. pp. 55-68 in: Environment and Breast Cancer. (ed. Russo, J.). New York: Springer.

Ratcliffe, D.A. (1967) Decrease in eggshell weight in certain birds of prey. Nature 215:208-210.

Richter, C.A., Birnbaum, L.S., Farabollini, F., Newbold, R.R., Rubin, B.S., Talsness, C.E., Vandenbergh, J.D. & vom Saal, F.S. (2007) In vivo effects of Bisphenol A in laboratory rodent studies. Reproductive Toxicology 24:199-224.

Vogel, S.A. (2009) The politics of plastics: The making and unmaking of Bisphenol A 'safety'. American Journal of Public Health 99:S559-S566.

Readers are encouraged to visit the website of The Endocrine Disruption Exchange (TEDX: http://www.endocrinedisruption.com/home.php) and to watch an excellent video by its Founder, Dr. Theo Colborn, discussing the general problem of endocrine disruptors in the environment.

Acknowledgement: Background research into endocrine disruptors, including the history of DDT and DES, was conducted while the author benefited from a fellowship at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (South Africa) in September-December 2016.