Confidence

Performance: Dissonance and Consonance

Are you performing in your right mind?

Posted February 20, 2023 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- The fluidity of one's performance, no matter how unique, depends on the cross-brain integration of the two hemispheres.

- Consonance or synchronicity within performance evolves when one's cross-brain integration processes refine and eventually eliminate dissonance.

Are you performing in your right mind (Wilson, 1993)? The two hemispheres of our brain have very disparate functions. The left hemisphere of our brain is very cognitive. It controls our speech, comprehension, numerical skills, and writing. The right hemisphere controls our creativity, spatial ability, and artistic and musical skills. To some degree, these incongruent functions are always at play in any performance we undertake. Perhaps this at least partially explains some of our most embarrassing performance gaffes.

The fluidity of our performance, no matter how unique, depends on the cross-brain integration of our two hemispheres. The synchronicity of some cognitive and some spatial skills, incorporated in time and in situ, yields a successful performance.

Consider the last time you had an unexplainable breakdown in your performance. It may have been a spatial demand that was unmet because you were in your head too much. Or, it may have been a cognitive processing demand that was challenged and not met.

Highly regarded musical performers have confessed to at times demonstrating anomalies of atonality that seem to come from nowhere. A similar pattern of unexplained performances has haunted golfer Bruce Koepka, who won four major tournaments in two years and has been failing to make cuts on the tour ever since.

What are the reasons for such disparities in performance? Is there something happening within the performer that even the performer is oblivious to? How might they get this awareness back into focus and improve their performance?

Dissonance

“Life is a desert of shifting sand dunes. Unpredictable. Erratic. Harmony changes into dissonance, the immediate outlives the profound, esoteric becomes cliched. And, vice versa.”—Ella Leya

Dissonance is usually referenced to be about cognitive dissonance. However, dissonance can theoretically be any lack of synchronicity or harmony; any lack of agreement between or within people or things.

So, why not performance dissonance? Surely, we can see detriments to performance as being related to some form of dissonance or incongruity in the performer. We even say, “I was out of sync.” Or, in a team setting, “we were not on the same page.” Repetitious phrases like these tend to substantiate the purported reality of a concept of performance dissonance. So, how do we reach consonance?

Consonance

“Let us light our lantern: in textbook language, dissonance is an element of transition, a complex or interval of tones that is not complete in itself and that must be resolved to the ear’s satisfaction into perfect consonance.”—Igor Stravinsky

Although Stravinsky is talking about music, he could have easily been talking about an accountant, an athlete, a chef, or a dentist. The ear can be depicted as a kind of metaphor for the cross-brain integration that either supports or denies one’s performance.

When we stay with the example of our ears, one only needs to think of how “white noise” can interfere with our ability to focus on the task. Ask any professional golfer about extraneous noises while in the middle of their backswing. Dissonance melts down performance like a heat wave in the Arctic. Consonance or synchronicity within performance evolves if and only if our cross-brain integration processes refine and eventually eliminate dissonance.

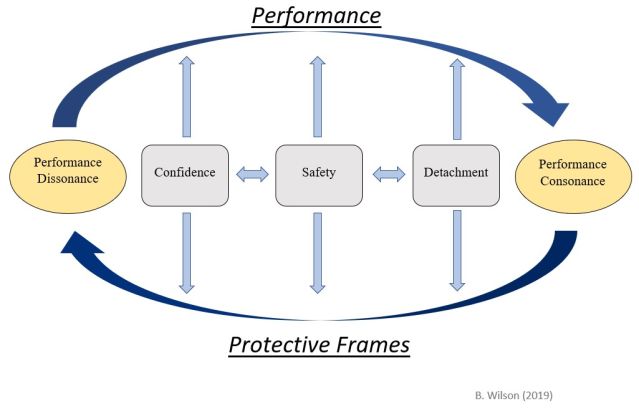

The Deconstructing Competitive Commitments Model (B. Wilson, 2019) suggests that the protective frames concept (Apter, 1992), can be applied to clients who are dealing with a competitive commitment in their performance. The model provides a structural basis to explore, with the client, potential protective frames that may be contributing to the client’s dissonance in their performance. The model is circular rather than linear due to performances alternating between the usual ups and downs.

As the model displays, clients are stuck between two oppositional commitments that are constantly being reinforced by their own inappropriate protective frames. An inappropriate confidence frame could lead to injury, either physical or mental. An inappropriate safety frame combines with anxiety, which interferes with the performer’s sense of “flow” Csikszentmihalyi (2008), either physical or mental. And, an inappropriate detachment frame allows any form of distraction to interfere with performance. These inappropriate protective frames have the potential to keep the client in a state of dissonance for as long as the client is willing to resist their need for change.

The effective therapist or coach will work with the client to help identify any inappropriate protective frames that might be contributing to the competitive commitment at hand. This process has the potential to be a catalyst for the client’s insight and personal agency. By eliminating inappropriate dissonance, performance consonance can be restored.

To find a therapist, please visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

References

Apter, M.J., (1992). The Dangerous Edge: The psychology of excitement. New York, N.Y.: Free Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2008). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper Perennial.

Wilson, B. (1993). Are You Competing In Your Right Mind? Sport Coach April-June, !993.

Wilson, B. (2019). The Deconstructing Competitive Commitments Model. The Counsellors Café (UK).