Fear

Are Fears Of Self-Compassion Holding Us Back?

Research suggests overcoming fear of compassion aids personal growth.

Posted November 20, 2017

Fear of compassion interferes with therapeutic efforts

Self-compassion is a core aspect of self-care, and goes along with being able to be kind and curious toward oneself, rather than harsh, full of shame, and blaming. Arguably, feeling kind and nurturing toward oneself should be the rule and not the exception, gentle yet firm while holding oneself responsible, self-engaged and positive while self-governing, and generally upbeat and interested in learning and growth when life presents challenges, and relaxed and receptive when things are going well.

Compassion for others is essential for creating a social environment where warmth and collaboration set the stage for constructive navigation of conflict, and more enjoyable time together when things are going smoothly. Whether related to personal growth in general, or as a factor which can impede or facilitate psychotherapy in particular, compassion for others and oneself, and fears of compassion, are important to identify and work on in order to enjoy solid results.

Research supports the presence of a key role for compassion-based perspectives. As Gilbert and colleagues note (2014), "Since compassion and the affiliative emotions associated with compassion play a fundamental role in emotion regulation, individuals who are blocked or fearful of accessing these emotions are likely to be struggle with emotional regulation and the psychotherapeutic process. Research on the fears of compassion and affiliative emotions suggests these are important therapeutic targets."

Training compassion may catalyze positive change and facilitate therapeutic efforts

Enhancing self-compassion may improve therapeutic outcomes, in general and for specific groups, for example in adult survivors of sexual abuse (McLean et al., 2017), depression (Zhang et al., 2017) and in eating disorders (Kelly et al., 2013). Miron and colleagues (2015) found that fear of self-compassion, compounded by a lack of psychological flexibility, was associated with more severe posttraumatic symptoms. Scholars have suggested that impaired self-compassion may be deeply implicated in adverse outcomes following childhood abuse, and that self-compassion training may be a powerful tool to improve outcomes (Miron et al., 2016). In my clinical and personal experience, I have found compassion-based training and loving kindness approaches to be effective, even transformative (see below for resources related to fostering compassion and loving kindness). Building compassion, for oneself and others, may facilitate forgiveness, gratitude, and generally bolster resilience, offsetting the effects of excessive empathetic engagement, enhancing neuroplasticity and shifting the balance from negative to positive emotional interpretations (Klimecki et al., 2014; Klimecki, 2015). If we are truly compassionate, I believe we are not able to feel compassion differently for ourselves than for others; compassion and empathy work together to find a balance and get us out of the dichotomy of selfish versus selfless.

Why do fears of compassion and low self-compassion impede recover?

Especially when we have experienced adversity growing up, and moreso when caregivers have not provided a sense of caring out of kindness, compassion and unconditional love, we may have developed motivational habits arising out of fear and self-criticism. We may feel inside that we are no good, even reprehensible in some way, that we are undeserving of anything positive, and even that seeking to have basic needs for care and human connection met are a sign of selfishness. We are supposed to be "selfless", which sometimes really means being self-sacrificing to the point of being masochistic. Such stories are all too familiar, sadly. Rather than being motivated by healthy pride and heartfelt desire, in the absence of self-compassion and self-love, we are motivated by avoidance of punishment, harsh self-attacks and negative self-talk. We do things not because we want to, but because we have to.

Rather than feeling a sense of agency and choice, we feel cornered and often despairing. Instead of feeling a sense of meaningfulness and purpose in our actions, we may feel they are meaningless and pointless, that we are merely going through the motions. In the place of balanced self-regulation and good self-care routines, we may become quickly dysregulated, and used self-destructive means to manage unpleasant emotional states, including food, alcohol and substances, and problematic relationships with others, or even dissociation. When we do accomplish something, we may be unable to appreciate it or take any credit or sense of healthy pride at all. We may give all the credit to someone else in an attempt to appear humble or selfless, or we may minimize our own contributions, or we may over-inflate our victories and alienate others. We tend to feel mistrust of others, as caregivers have often been sources of neglect, abuse, inconsistency, and even betrayal.

With these self-effacing habits firmly entrenched, making use of good care, for example from ourselves, from loved ones, from therapeutic professions, in the workplace, and so on, is fraught with fear and perceived dangers. Rather than heading in the right direction, we avoid self-compassion and kindness from others because they can be frightening, unfamiliar and uncertain. I've chosen to highlight barriers to compassion rather than assessing compassion directly because identifying roadblocks can help target areas where adaptive habits will be most effective. The Fears of Self-Compassion Scale can help us map out areas of vulnerability where we can work on our ability to practice compassion for ourselves and others.

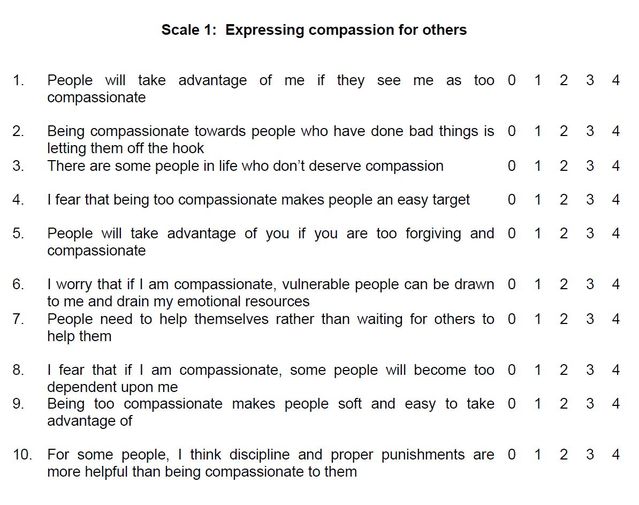

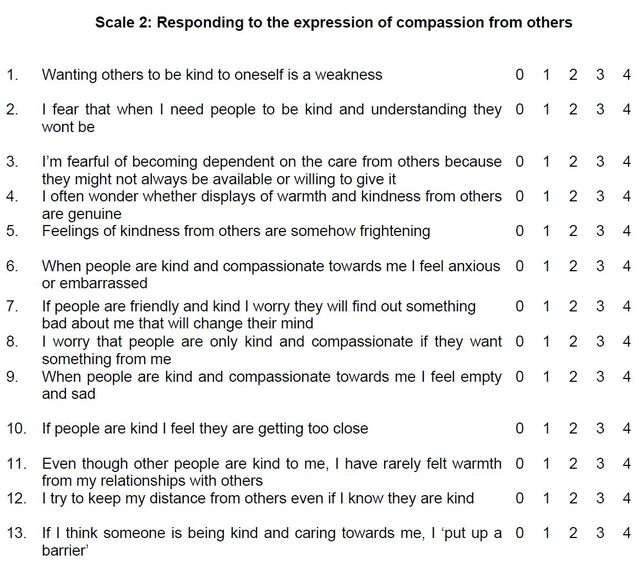

Fears of Self-Compassion Scale

In order to help people understand barriers to self compassion, Gilbert and colleagues (2011) developed the "Fears of Self-Compassion Scale". This scale is evidence-based and validated, looking at three dimensions: 1) Expressing compassion for others; 2) Responding to compassion from others; and 3) Expressing kindness and compassion towards yourself. Each item is rated by how much we agree or disagree with the associated statement, and instructions are below. Please note that the items on the scale are designed to pinpoint core issues related to how we feel about oneself and others, and therefore be aware and ready for the possibility of strong emotional reactions. If you are concerned you may have a very negative reaction, I advise you do not complete this scale, and instead save it for a time you can work on it with someone supportive (e.g. someone close to you who can review it first, a therapist, a coach, etc.).

FEARS OF COMPASSION SCALE

Different people have different views of compassion and kindness. While some people believe that it is important to show compassion and kindness in all situations and contexts, others believe we should be more cautious and can worry about showing it too much to ourselves and to others. We are interested in your thoughts and beliefs in regard to kindness and compassion in three areas of your life:

1. Expressing compassion for others

2. Responding to compassion from others

3. Expressing kindness and compassion towards yourself

Below are a series of statements that we would like you to think carefully about and then circle the number that best describes how each statement fits you.

Rate each item on a scale from 0 1 2 3 4 where "0" indicates "I do not agree at all", to "Somewhat agree" to "4" indicating "Completely agree". To score, add up the number to get a total for each section, and overall. The higher the score, the greater the fears of compassion.

Further Considerations

If you have gone through the above exercise, you may have gotten some surprises (or perhaps not), you may have experienced relevant self-referential thoughts and emotions, and it may take some time to process. Often, when I've used this work, it has been overall positive, helping to define areas of work, fostering optimism even if stirring up sadness or frustration, and even providing relief that many people can relate to the experience of struggling to give and receive care from others, and toward oneself. Recovery from adversity can take work, and compassion-based training is not a substitute for longer-term efforts. Looking for quick solutions makes sense when they can produce positive change in a short time, but can backfire when they are ineffective or interfere with longer-term efforts toward change by replacing the reality of persistent effort with the fantasy of a magic bullet.

Compassion-based work can help us to approach ourselves (and others) with a gentler, loving, curious and more flexible attitude that may be just enough of a nudge in the right direction to be useful, and lay the foundation for more enduring constructive habits of how we address problematic issues, as well as joyful experiences. The difference between having a blaming mindset and a compassionate mindset may be the difference between having that moment of self-connected reflection during which we make a better decision, and that moment when we make a fast decision we sometimes regret. The goal is to learn to reflexively make better decisions, and be able to slow down when needed.

Resources:

Dr. Kristen Neff, Mindful Self-Compassion

Greater Good In Action, Berkeley

Emory-Tibet Partnership, Cognitively-Based Compassion Training

References

Gilbert P, McEwan K, Matos M & Rivis A (2011). Fear of compassion: Development of a self-report measure. Psychology and Psychotherapy. http://self-compassion.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/fears-of-com….

Gilbert P, McEwan K, Catarino F, Baião R (2014) Fears of Compassion in a Depressed Population Implication for Psychotherapy. J Depress Anxiety S2:003. doi:10.4172/2167-1044.S2-003.

McLean L, Steindl S R, & Bambling M. (2017). Compassion-focused Therapy as an Intervention for Adult Survivors of Sexual Abuse, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, Sept. 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2017.1390718.

Kelly AC, Carter JC, Zuroff DC, Borairi S. (2013). Self-compassion and fear of self-compassion interact to predict response to eating disorders treatment: a preliminary investigation. Psychother Res., 23(3):252-64. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2012.717310.

Miron LR, Sherrill AM, Orcutt HK. (2015). Fear of self-compassion and psychological inflexibility interact to predict PTSD symptom severity. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 4, 37–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.10.003.

Miron LR, Seligowski AV, Boydkin DM, Orcutt HK. (2016). The potential indirect effect of childhood abuse on posttraumatic pathology through self-compassion and fear of self-compassion. Mindfulness, February 18. DOI 10.1007/s12671-016-0493-0.

Klimecki OM, Leiberg S, Ricard M, Singer T. (2014). Differential pattern of functional brain plasticity after compassion and empathy training. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014 Jun;9(6):873-9. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst060.

Zhang H, Watson-Singleton NN, Pollard SE, Pittman DM, Lamis DA, Fischer NL, Patterson B, Kaslow NJ. (2017). Self-Criticism and Depressive Symptoms: Mediating Role of Self-Compassion. Omega (Westport). 2017 Jan 1:30222817729609. doi: 10.1177/0030222817729609.

Klimecki OM. (2015).

The plasticity of social emotions. Soc Neurosci. 2015;10(5):466-73. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2015.1087427.