Ethics and Morality

Catastrophe in the Philippines: Coping with Cosmic Evil

How can we psychologically cope with catastrophe?

Posted November 16, 2013

What are the psychological effects of massive natural disasters like the devastating typhoon that pummeled the Philippines? The killer earthquakes in Japan and Haiti ? The cyclone in Myanmar (Burma) that claimed as many as 100,000 victims? The 2004 Indonesian earthquake and tsunami in which more than 200,000 perished? Hurricane Katrina? What are the psychological, theological and philosophical issues victims of such tragedies struggle with? And what about the rest of us who witness such excessive suffering even from afar? Are we psychologically immune? How do catastrophic phenomena, natural disasters, so-called "acts of God," affect the human psyche?

To be so suddenly and catastrophically confronted with the stark reality of evil--of suffering, destruction and death--can be a shattering experience, a profound existential crisis. Let's first make a distinction between natural evil and human evil: While, as a forensic psychologist, I have frequently written here about evil deeds--human destructiveness--now we are speaking about nature's own destructive evil. Can nature be cruel? Clearly. Evil is an existential reality, an inescapable fact with which we all must reckon. Virtually every culture has some word for evil, an archetypal acknowledgment of what Webster defines as "something that brings sorrow, distress, or calamity . . . . The fact of suffering, misfortune, and wrongdoing." We witness human evil every day in its various subtle and not-so-subtle forms, though we often tend to deny its reality. Denial is a powerful and comforting psychological defense mechanism. Or we attempt to neutralize evil, dismissing it as maya or illusion, as in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions. Indeed, it is tempting to deny the reality of evil entirely, due to its inherent subjectivity and relativity: "For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so," says Shakespeare's Hamlet, presaging the cognitive therapies of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck. With the notable exceptions of C.G. Jung, Rollo May, M. Scott Peck and a few others, psychology and psychiatry have, until very recently, traditionally steered clear of speaking of the problem of evil per se.

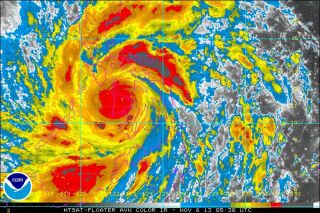

But denial and avoidance can no longer protect us when evil strikes in suprahuman, transpersonal, cosmic occurrences such as drought, disease and tragic accidents that wreak untimely death and destruction on multitudes of innocent victims. Especially when we are directly and personally affected. How do we make any sense of and accept it? For the Filipino people hit by the strongest typhoon in recorded history, existence has taken the harshest of turns.Thousands are dead. Corpses, often those of close family members, decompose in the streets under the sweltering sun. Survivors are still without food, shelter, water or medical attention. For many of those who do barely survive such events, cheating death, the symptoms of acute stress disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder will likely develop, necessitating some therapeutic intervention.That is, when and if such psychological assistance is available, which, for the Filipino people, it presently is not. And it is unlikely that the vast majority of victims suffering PTSD symptoms will ever see a mental health professional.

People suffering from ASD (acute stress disorder) or PTSD are initially in a state of emotional shock or "psychic numbing," as psychiatrist Robert Lifton termed it. They have been precipitously exposed to either natural or human evil, or both, and unable to psychologically digest and process the experience. Denial is no longer a viable defense. They feel out of control, victimized, helpless, powerless, frightened, disillusioned. Often, they also feel angry and embittered about what has happened. Angry at god. Or with fate or life itself. They have abruptly and brutally been stripped of their childish belief in life's inherent fairness. In God's goodness. In a benign universe. Their comforting Weltanschauung (worldview) has been shattered. Many will never be the same. Like Humpty Dumpty, the bits and pieces cannot be put back together exactly as they were. Some who survived the typhoon will not survive the traumatic emotional and physical aftermath.

Psychology can help, but is certainly not the only means of coping with cosmic evil. There has long been religion. The Philippines is a predominantly Roman Catholic and very religious country. The people have the support of their religious beliefs to sustain them in times of terrible trouble, when evil strikes for no rhyme or reason. But even so, facing the harsh reality of evil strains spiritual faith. The biblical Book of Job addresses just this subject, as do all major religions worldwide. Job, as some may recall, was a good and religiously devoted man upon whom Yahweh allowed Satan to suddenly shower all manner of misery, misfortune and suffering. Job almost entirely loses his family, fortune, and physical health. But despite his resentment toward Yahweh for such unfair and undeserved treatment, Job never renounces God, recognizing and accepting instead God's absolute right to "giveth and taketh away," regardless of how we puny humans judge such events in terms of "good" and "evil." His faith was sorely tested, but in the end, a new life became possible. Job still has much to teach us. But for many today in Western culture, religion has been replaced by psychology when it comes to coping with life's inevitable and tragic suffering. Like the priest, rabbi, monk or cleric, psychotherapists and mental health workers such as Red Cross counselors who deal with victims of cosmic evil are confronted daily with these same profound questions Job pondered: Why is there evil? Where does it come from? If there is a God, how could he (or she) condone it? Why me? Or why not me, as in the case of "survivor guilt." Why am I still living? Why was I ever born? For many modern people, organized religion no longer works in providing solace or satisfying answers to such troubling existential questions. After graduating from Union Theological Seminary, Rollo May served for three years as a Congregational minister prior to becoming a clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst. He felt frustrated that the only time his counseling with parishioners seemed helpful was during funerals, when the intense existential reality of death and their powerful feelings could not be denied. This is why May decided instead to become a psychotherapist.

Even for the emotionally detached, spiritually enlightened, scientific or geographically distant observer, the grotesque spectacle and scope of natural evil can be traumatic. At some level, we know that any of us could suffer the same or a similar fate someday. This is especially true for individuals with a history of previous psychological or physical trauma.These existential, philosophical and theological queries run deep, and can be consciously or unconsciously stirred up by such unsettling events. Natural disasters psychologically shake the very ground of our existence, causing us to question the fundamental nature and meaning of life--and death. They force us, in the starkest possible way, to see the existential fact of life's slender, tenuous thread: that being can at any moment become non-being; that death is always but a breath or heartbeat away; that the basic structure we daily depend upon for meaning and safety is in reality quite transitory and fragile. Such calamities sometimes lead to precariously dangerous states of mind: depression, rage, nihilism, panic, chaos, even psychosis. They can negate one's sense of security and predictability, causing severe anxiety states. And they can rattle our religious faith, resulting in disillusionment, despair, addiction, sexual acting out, violence, and sometimes suicide. So it is imperative that psychotherapists themselves are properly prepared to address such philosophical and spiritual issues in ways which will help victims courageously face and cope constructively with the perennial problem of evil: evil of both the human and natural variety. We each must consider how we would cope with disaster. What is it that human beings need to get through such hellish situations? Perhaps strangely to some, one answer is meaning. As the late existential psychiatrist and death camp survivor Viktor Frankl (1946) noted, paraphrasing Nietzsche, if it can be found, some meaning or sense of purpose makes almost any suffering more bearable: "He who knows the 'why" for his existence will be able to bear almost any 'how'."

What the victims of this awful natural tragedy in the Philippines need right now, perhaps equally as much as fresh water, food, shelter and medical treatment, is a "why," a reason to live and rebuild their broken lives. (One now homeless young man I saw interviewed on CNN who had lost his wife and family, said he seriously considered suicide, but chose to stay alive because his one surviving daughter needed him.) Some sense of purpose in survival. A way of making meaning out of meaningless chaos. Of seeing light through the darkness. Of finding faith beyond despair. If their religious beliefs provide such strength, courage and meaning, helping them to tolerate and transcend tragedy, this is evidence that organized religion remains a viable psychological and spiritual force for good in the modern world. And that, for those secular victims of catastrophe, psychotherapy must serve essentially the same purpose as did religion traditionally when it comes to dealing with life's unpredictable disasters, suffering, and the existential problem of evil: to provide support, succor, encouragement, meaning and purpose to people in desperate, intolerable and seemingly insurmountable circumstances.