Personality

Sherlock and Oprah: How to See People as They Are

Here's what we are learning about being good judges of personality.

Posted May 10, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Research finds that people who are psychologically healthy tend to be better judges of personality.

- Good judges of personality often do not operate via keen insight and attention to detail.

- Instead, they create positive atmospheres that allow others to feel comfortable expressing their true selves.

My mother has a story that has become famous among my students. The short version goes like this: Many years ago, when she was a teenager in a new town, a young man asked her out on a date, and she was quite excited about the prospect. As was customary, the fellow had to first meet her father (think late-career Al Pacino here). When the moment arrived, the suitor was rejected with extreme prejudice on the basis of a handshake and a quick verbal exchange. No clear explanation was given. My mother was devastated.

The story’s happy ending was when my mother later met my father and had me, thus allowing you to hear the weirder part of the story. Many years later, an envelope addressed to my mother by her father arrived in the mail—a rare occurrence for him. Inside the envelope was not a letter but rather a newspaper clipping detailing the thwarted suitor’s recent arrest for the brutal murder of his domestic partner.

I often tell this story to my students to open up a conversation about what constitutes a “good judge” of personality. Many times, student have their own similar stories about omniscient grandmothers and uncanny uncles who can see things in people that elude others—and they can do so quickly. Is this a real ability? If so, what makes it possible?

A Framework

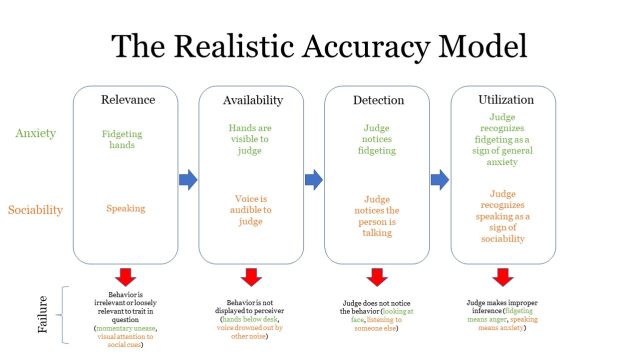

To study this, personality psychologists often employ David Funder’s (1995) Realistic Accuracy Model, which is an extension of Ego Brunswik’s (1956) older and more general Lens Model. These models are frameworks for understanding how we make inferences about causal properties within people—such as personality characteristics (which are not readily observable per se)—using what I’ll term cues or observable features of a person or actions the person takes. For example, if someone insults you at a cocktail party, you may infer from that behavior that they are, in general, not very nice. If, instead, they stay after to help the host clean up, you may infer that they are generally helpful. These are tidy examples, but the path from cue to accurate judgment is fraught with peril.

According to Funder, in order to arrive at an accurate judgment about a given personality trait in a given person, the judge must have four conditions met. First, the characteristic that you wish to judge must have relevant manifestations in cues. That is, there must possibly be a way to observe an indicator of this thing. This can be tricky if what you wish to learn about someone pertains to their internal emotional stability or clandestine ill will.

That said, most personality characteristics do have relevant markers, so this one is a question of degree—how closely does the manifestation match the underlying disposition? These markers may not always be available, however. Availability here simply means that there exists an opportunity for the judge to observe the relevant cue. If someone is nervous, they fidget or tremble, making the underlying anxiety available to the judge. But, the judge must then detect this slight tremble in order for it to aid in the overall judgment process.

Finally, the judge must properly utilize what they have detected. This means that the judge must have an accurate understanding of how the observed cue connects to an underlying personality characteristic. If one detects a fidget and assumes it’s a marker of boredom instead of anxiety (when, in truth, it’s the latter), they fail in the utilization phase of the Realistic Accuracy Model.

Thus, for accuracy to occur, relevant cues must be available, detected, and properly utilized by the good judge, and what makes someone a good judge probably works somewhere along this chain of events.

Murky Waters

Before we can tackle what makes a good judge, the first question is whether there is even such a thing. The answer seems to be yes. Researchers have demonstrated that people who can accurately assess one person can often also accurately assess other people. In other words, personality judgment accuracy is (at least somewhat) reliable. Maybe your intrepid granny is indeed onto something. But how? Why? Or if you’re someone (like me) who’s made mistakes in character judgment, why not me?!

Early hypotheses—and sensible ones—fell into what I would call the Sherlock Holmes meta-theoretical perspective and searched for individual differences in people that may give them an advantage in the process. In other words, maybe my mistakes are because I am not very astute or attentive. Indeed, some studies found that intelligence (Vernon, 1933) or some judgmental ability (Taft, 1955) predicts judgment accuracy in personality. This would make sense in that intelligent people utilize information effectively, and conscientious people may pay better attention to detail and thus detect things others do not. However, many other studies failed to demonstrate such relations, and in general, the search for robust and specific predictors of judgment accuracy has been fairly fruitless (Davis & Kraus, 1997).

A Candidate Emerges

One class of individual differences, however, has emerged over time as a fairly robust marker of judgmental accuracy: traits related to good overall psychological adjustment. Folks who are psychologically healthy (which often involves being happy and pleasant and such) are good at judging others (e.g., Hall et al., 2009; Human & Biesanz, 2011). This doesn’t exactly square with a Sherlock Holmesian model of the good judge, as this quality may or may not be associated with individual differences that provide advantages for detecting or utilizing information. However, it is possible we have been barking up the wrong tree.

One of my favorite investigations into the good judge phenomenon was Dr. Tera Letzring’s (2008) study, in which she asked groups of three unacquainted individuals to get to know each other (in various different ways). These people then rated their own and each other’s personalities, and thus, the accuracy of any given judge could be determined by comparing their judgment of an interaction partner with that person’s actual personality characteristics (as indexed by a composite of their view of themselves and some knowledgeable others’ views of them). As suggested above, Letzring found evidence that good judges exist. That is, there are people who make better-than-average accurate assessments of more than one other person.

With that established, one can start looking for potential reasons. In this case, Letzring recorded these three-person interactions, which enabled two further analyses. First, independent observers could watch these videos to see what good judges did. It turns out that better judges tended to do things like make eye contact, emphasize the accomplishments of close others, and express warmth and seemed to be enjoying themselves. Hardly Holmesian behaviors.

Letzring did not stop there. She then asked other people to view these interactions and assess the personalities of the interactants. What she found here was that people who interacted with more good judges were judged more accurately by people viewing videos of these interactions. Taken together, these findings suggest the possibility that good judges may not operate via keen insight and attention to detail but perhaps instead by creating positive atmospheres that allow others to feel comfortable expressing their true selves (i.e., via relevance and availability as opposed to detection and utilization).

Now What?

When I first read this paper, I was surprised and excited by this finding. In retrospect, this seems obvious—what makes a good talk show host or interviewer? But at the time, for me as a then-young personality psychologist, it was just something I had not fully considered, perhaps embarrassingly. As I considered it further, one potential complication of the study’s design was that it was possible these people who interacted with good judges just happened to be good targets (people who are easy to read; Human & Biesanz, 2013), and perhaps the good judges were not eliciting authentic behavior but simply consuming it. The behavioral data suggest otherwise, but we cannot discount the possibility without employing a different design. Recent research suggests that in order for good judges to emerge, good targets may be a necessary condition (Rogers & Biesanz, 2019)—so apparently, one cannot easily pry open a closed book.

As a long-time friend and collaborator of Dr. Letzring, I had always imagined we would work on this problem together sometime in the future. Her recent untimely passing has both rendered that impossible and motivated me to pick this up again. Along with some equally motivated (and more talented) colleagues, I am actively planning some upcoming projects in the hopes of helping to demystify certain aspects of the good judge. I hope to be able to report something interesting in the coming years. In the meantime, here is some tentative advice for aspiring people-readers: Instead of picking up your magnifying glass to find what is hidden, try channeling your inner Oprah to have someone show it to you.

References

Brunswick, E. (1956). Perception and the representative design of psychological experiments. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Davis, M. H., & Kraus, L. A. (1997). Personality and empathic accuracy. In W. J. Ickes (Ed.), Empathic accuracy (pp. 144–168). The Guilford Press.

Funder, D. C. (1995). On the accuracy of personality judgment: a realistic approach. Psychological review, 102, 652-670.

Human, L. J., & Biesanz, J. C. (2011). Through the looking glass clearly: accuracy and assumed similarity in well-adjusted individuals' first impressions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 100, 349-364.

Human, L. J., & Biesanz, J. C. (2013). Targeting the good target: An integrative review of the characteristics and consequences of being accurately perceived. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17, 248-272.

Letzring, T. D. (2008). The good judge of personality: Characteristics, behaviors, and observer accuracy. Journal of research in personality, 42, 914-932.

Rogers, K. H., & Biesanz, J. C. (2019). Reassessing the good judge of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117, 186–200.