Genetics

The Next Step in Canine Behavioral Genetics

The unveiling of a bold effort to re-sort dogs

Posted February 15, 2023 Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

Key points

- Genetic studies of dogs have often found that breed does not determine a dog's behavior.

- New research suggests lineages, not just individual breeds, better group dog behaviors.

- These 10 suggested lineages offer scientists new ways to examine the common traits across dog breeds.

Following my May 2022 post about Elinor Karlsson’s Science article on the genetic survey of dogs through the Darwin’s Ark project, and its conclusion that a dog’s breed does not predict its behavior, I received several comments aimed at debunking that conclusion.

Karlsson and her collaborators found that “Breed offers little predictive value for individuals, explaining just 9 percent of variation in behavior.” Nonetheless, dissenters insist that their sheltie, for example, exhibits behaviors that are common to all shelties and, indeed, help identify the pint-sized collies.

Another recent paper, "Domestic Dog Lineages Reveal Genetic Drivers of Behavioral Diversification," published in the December 8, 2022, issue of Cell, cast further light on such questions.

Elaine Ostrander, who heads the Cancer Genetics and Comparative Genomics Branch of the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health, has been pursuing answers to questions regarding the genetics of behavior for several decades. She collaborated with her post-doc Emily Dutrow and James Serpell of the department of Clinical Sciences and Advanced Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Their lengthy paper proposed a new way to look at the issue of breed-specific behavior that they hope will open the door to more studies. Essentially, they took dogs from 226 breeds represented in the Federation Cynologique Internationale (FCI) and re-sorted them according to lineages that share behavioral and sometimes morphological characteristics.

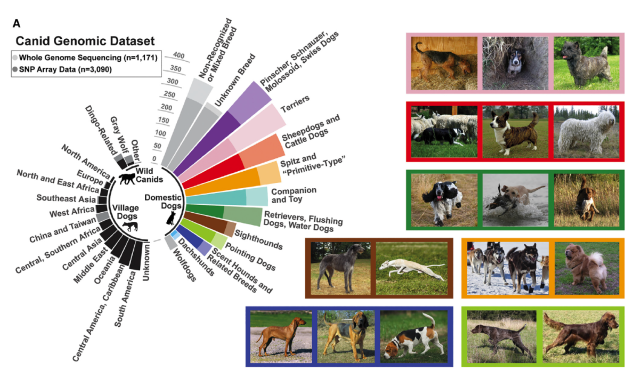

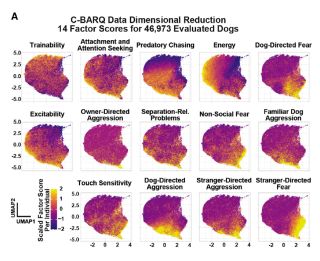

To reach their conclusion, they collected genetic data from some 4,000 domestic, semi-feral, and wild dogs and behavioral data from over 46,000 dogs. That produced 10 lineages, including Terriers; Sheepdogs and Cattle dogs; Spitz and so-called “Primitive Types”; Companion and Toys; Retrievers; Flushing dogs and Water dogs; Sighthounds; Pointing dogs; Scent Hounds and related breeds; and finally, Dachshunds. The study also included dogs of indeterminable breed, along with village dogs and wild canids like the gray wolf.

The researchers suggested that the behavioral diversification of dogs predates modern breed formation and that ancient non-coding genetic variations drove this variety.

Most importantly, Dutrow pointed out in an email to me that the researchers let genetics drive the categories rather than the human-defined behaviors or appearances. As she explained:

We reframe the question of dog behavior as simply: what is fundamental to making a herder a herder, genetically, versus a terrier, etc? Therefore, underlying this ordering of individuals into lineages is a complex genetic signature that we propose should include variants conferring their shared behavioral tendencies.

What is interesting about these groups is that they include dogs that work around sheep, for example, in quite different ways: Border collies and kelpies are active herding dogs who control the animals by giving “eye," while big livestock guarding dogs like the Great Pyrenees tend to move with the animals as escorts rather than actively herding them.

Yet all three breeds are members of the Sheepdog and Cattle dog lineage. The key is to find the deep sources of their affinity for “herding.” We are not dealing with a simple lockbox of traits but rather a whole suite of potential behaviors mixed and matched in virtually every dog.

"This explains," said Dutrow, "why both individual dogs and entire breeds are capable of performing behaviors that they are not necessarily ‘meant’ to perform,” and, presumably, vice versa: the retriever who won’t swim.

Many of these behaviors are common wolfish behaviors amplified or emphasized through human-imposed artificial selection combined with natural selection in the case of the landrace animals.

This new paper both complicates and simplifies the genetic basis of behavior. The graphics do an excellent job of illustrating that complexity. The bottom line, of course, is that there clearly is a genetic component to specific behaviors or behaviors more common to specific breeds than others.

But there is also a great deal of variation within those breeds and, in this case, lineages, and this variation is the result of a whole host of factors, many of which are not due to specific proteins, but rather to regulatory forces that nudge an individual’s genome in one direction or another.

Those directions must all be within the confines of what it means to belong to that lineage of “terrier” or “herder” or others. The extensive analysis to which Dutrow and her colleagues subjected their samples indicates that the entire base splitting into lineages came earlier in the dog’s development, which helps explain why some types of dogs seem more basic than others.

Finding those pathways is, of course, no easy task, as evidenced by the recent dust-up over oxytocin, which I hope to cover here soon. For now, suffice it to say I see no great, unbridgeable gap between this study and the one by Karlsson and her colleagues of last spring.

I thank Daniel Elliott for his assistance in researching this post.

References

K. Morrill et al., Science 376, eabk0639 (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abk0639

Dutrow et al., 2022, Cell 185, 4737–4755 December 8, 2022. Published by Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.003