Loneliness

How to Design Spaces for Human Connection

Building communities and cities to combat loneliness and foster connection.

Updated May 14, 2024 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- The built environment has a role in combating social isolation and loneliness and in fostering connection.

- Interconnected physical spaces shape our cities and communities, from homes, to streets, parks, and more.

- Social connectedness can be boosted via design, planning, and policy, and across stakeholders.

Co-authored by Erin Peavey & Risa Wilkerson

We humans are inherently social creatures, thriving on interaction, collaboration, and community. Yet, we often drive alone in cars, walk on treadmills wearing headphones, or work in commercial parks that feel nothing at all like a park. Small wonder that our friendships and in-person social networks are decreasing. Our communities are designed for us to make these choices. It doesn’t have to be this way.

Imagine a world where shared experiences and human-centered design knit communities together, where public transit hubs exude the energy of playgrounds, and empty spaces like parking lots and alleyways transform into hubs of connection. In this vision, essential services seamlessly integrate into residential areas, ensuring accessibility for all. It's a vision where no matter how we move about in our lives, we experience communal spaces that feel relevant and comfortable. Intrigued? Good. Because we can collectively transform our environments into catalysts for connection.

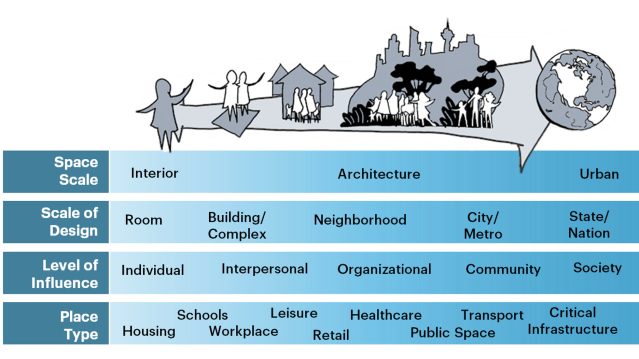

In the Foundation for Social Connection’s newly released Built Environment Sector report, we seek to answer just that. Co-chaired by the co-authors of this article, we dive into evidence-based and promising interventions related to the intersection of transportation, housing, and our environment. Additionally, we present untapped policy opportunities, important considerations, and research gaps to further explore. Using the Foundation’s SOCIAL Framework—a roadmap to advance connection in every sector of society and across the lifespan—leaders from all levels of influence can understand their role in reimagining our built environment and helping communities thrive. Below, we highlight key takeaways from the report.

By identifying how the design, planning, policy, and use of the built environment can negatively or positively influence our ability to be socially connected, the report helps shine light on the path forward. Here are a few highlights along each of these strategies:

- Design: Align with our evolutionary inheritance, tapping into the natural elements like complexity, human scale, and natural elements.

- Planning: Neighborhood and city planning in the last century typically focuses on a car-centric model of development, largely focused on moving people in vehicles. Focusing on how people are well and connected helps align priorities with a future that is more human-centric.

- Policy: Creating policy that incentivizes and systematizes an equitable focus on human well-being and social connection as it relates to physical infrastructure and housing helps shift the focus from short-term profit to long-term benefit.

- Use: If we want wonderful public and shared spaces, we need to use them. Host birthday parties at the park, go on walks with neighbors or friends, and frequent third places. As we use these spaces, we show we value and invest in them.

The SOCIAL report shares promising strategies for increasing social connectedness through the design, planning, policy, and use of built environments. For example, here are three of the nine strategies shared in the report, with real-world examples of each:

1. Design places to support comfort and connection:

- Description: Evidence-based design guidelines for creating places to foster social connection include sense of place, accessibility, nature, activation, choice, and human scale, also referred to by the acronym PANACHe. At the root, PANACHe strategies align with evolutionary needs for social connection—including sense of safety, proximity to others, and opportunities to connect.

- Example: In La Jolla, California, at UC San Diego’s recent learning and living neighborhood, these various strategies are evident from “nested scales of belonging” embedded into the structure of the building and experience as one moves through it. The research team found students in the new facility reported anecdotal improvements in connectedness and a significant reduction in depression scores.

2. Create third places that facilitate natural opportunities for connection:

- Description: Third places are shared spaces and environments outside of one’s traditional home and workplace. They can be both private (e.g., café) or public (e.g., city park) and can support social health and well-being.

- Example: In Atlanta, Georgia, StationSoccer sites now dot the landscape. These mini parks repurposed often vacant and forgotten slices of land into spaces of gathering, supporting youth sports and education, enhancing the public realm, and attracting new commercial and residential development, while fostering healthy and more equitable neighborhoods.

3. Build intergenerational and age-friendly communities:

- Description: Universal design of community spaces to ensure everyone not only has physical access but also feels welcome and included is essential. This shows up in big and small things, like the ease of opening a door to entry, use of the restrooms, choice of chairs, and programming that includes and reaches across generations. Not making something different—and, let’s be honest, often uglier—for one group of users versus the other, but rather providing choice and variety for all to tailor the space to their needs. According to a Generations United report, 92 percent of Americans believe that intergenerational communities can help reduce loneliness across all ages, yet only one in four individuals reported knowing of such a place in their own community.

- Example: In Jenks, Oklahoma, Grace Living Center is co-located with Jenks Public Schools' West Elementary to create intergenerational learning as a part of every day. Children and senior residents regularly engage in activities that enrich the social lives of all involved.

We don’t have to just imagine a socially connected community; we can design it! By prioritizing human-centric design principles and integrating inclusive policies and programming, we can transform our built environment into vibrant hubs of social connection, enriching the lives of individuals and strengthening the fabric of our communities.

Click here for the link to the full report to read all of the strategies and find out more.

References

Ewing, R. and Cervero, R. (2010) Travel and the built environment: A meta analysis. Journal of the American Planning Association. 76(3), 265–294. doi:10.1080/01944361003766766

Foundation for Social Connection (2024). The Systems of Cross-Sector Integration and Action across the Lifespan (SOCIAL) Framework in the Built Environment Report. Retrieved on May 2, 2024.

Generations United & The Eisner Foundation. (2018). All in together: Creating places where young and old thrive.

Peavey, E. & Holt-Lunstad, J. (2020) Is Your Environment Making You Lonely, Psychology Today

Peavey, E. (2023) Six Ways to Design for Social Connection and Community, Psychology Today